Published Jun 1, 2023

Preserving Our ‘Inner Light’

Our digital footprint, like the Kataan probe, allow us the opportunity to be like Kamin and leave behind a record.

StarTrek.com / Rob DeHart

“Trek Class” is a course at Syracuse University’s School of Information Studies titled “Star Trek and the Information Age.” The course examines episodes of Star Trek series as a method of introducing concepts related to technology, society and leadership in our world. This series of posts seeks to share some of the concepts discussed in Trek Class with the StarTrek.com community.

StarTrek.com

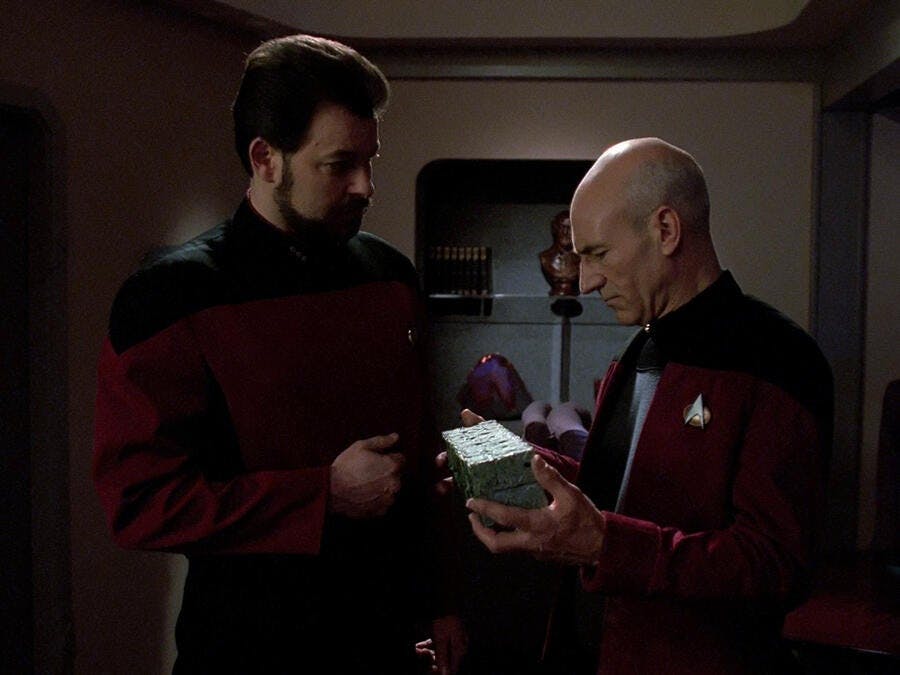

In the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode “The Inner Light,” the U.S.S. Enterprise-D encounters an unusual space probe which emits an energy beam at Captain Picard, causing him to lose consciousness on the bridge. As his crew struggles to revive him, Picard awakens on an unfamiliar planet where he appears to be living the life of a man named Kamin. Unable to determine the cause of his confusion, he begins to accept that his memories of the Enterprise were merely dreams.

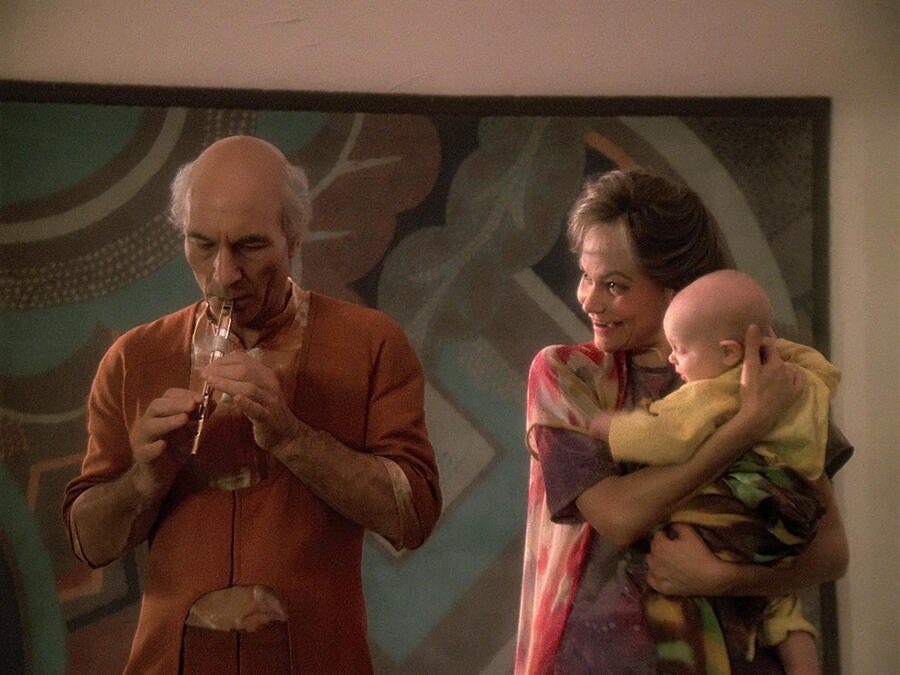

In what appears to be many years’ time, Picard experiences a full life as Kamin, complete with a wife, children, and an active role in his community. While working to address a long drought, he discovers that the planet itself is dying as a result of its sun’s impending nova. Unable to manage the space flight necessary to evacuate, the government has instead planned to launch an unmanned probe that will carry information about life on the planet Kataan. Having outlived his wife and many friends, an elderly Kamin witnesses the launch of the very probe that Captain Picard has encountered one thousand years in the future.

StarTrek.com

After regaining consciousness on the bridge of the Enterprise, Picard discovers that only 20 minutes have passed; yet he retains full knowledge of a life on Kataan. He is able to recall the memories and emotions of a man who lived long ago, even the ability to play a flute that he and his family so much enjoyed hearing. It seems that through this experience, Picard has become a living archive of a lost culture.

As we examined this episode in Trek Class, we found ourselves investigating some rather challenging questions, such as, “What happens to all the information we have created once we die?” Furthermore, if we are to leave behind a record of ourselves, we wondered, “How do we determine which information is most important to preserve?”

Although the space probe may have been designed to preserve a culture, Picard’s experience as Kamin proved to be a deeply personal one as well. The essence of an individual was captured so that he might live on in the memory of others. In our own world, it has long been possible to gather a similar sense of a person by examining letters, photographs, and other artifacts. However, as we continue to move toward digital forms of communication and expression, it can be difficult to preserve or even locate the information trail we leave behind.

StarTrek.com

Even as technology allows us to generate far more information about ourselves than had been previously possible, we must consider that we could actually end up leaving less behind for family and friends to remember if we take our passwords with us. Even if our loved ones are not locked out of our digital afterlives, it is daunting to imagine making sense of the thousands of unsorted photographs, endless emails and text messages, and hours of video recordings we may each accumulate. More challenging still is the task of preventing those items from being lost to time as file formats become obsolete and older technologies fail.

By taking steps to protect our personal information, we can increase the chances that our individual “space probes” will remain functional well into the future. While some services exist to help archive and manage digital affairs, for many it may be enough to maintain simple backups of the most meaningful items, and to organize those files in ways that would be accessible to others who may receive them after us. This process is not only helpful in preserving our contributions for the future, but it offers the opportunity to select elements of our own personal stories we most wish to share.

StarTrek.com

Thinking more broadly about cultural preservation, students in Trek Class offered differing opinions as to which information would be most important to include should Earth ever need to launch a Kataan-like probe. Some suggested that records of scientific discoveries would be most valuable. Others believed that artistic and cultural achievements would be a greater contribution, since anyone finding such a record would likely possess scientific knowledge of their own. But some felt differently still, believing that finding a way to preserve everyday life, as had been done with the Kataan probe, would be the most appropriate approach.

If an account of everyday life is indeed the best record to leave behind, then perhaps our digital lifestyles present opportunities in addition to challenges. As millions of people share thoughts and conversation on social networks, for example, a public record is being created that could provide a unique picture of life in communities worldwide.

StarTrek.com

In 2010, the Library of Congress announced that it would archive all public messages on Twitter since the service launched in 2006. With over 100 million “tweets” currently sent per day, the size and scope of this archive is difficult to imagine. However, it may hold tremendous value as tools are developed to examine this global conversation. We may soon be able to determine exactly how people in regions all over the globe felt, thought, and acted on important days in history, or simply on an average day.

With mobile devices, digital cameras, and social media, we are each creating a living record of our thoughts, conversations, and moments ranging from significant to ordinary. Though we may sometimes struggle to manage this content, together we are preserving an important picture of life around us. We may each have the opportunity to be “Kamin” for someone who will follow us, each offering our own experiences to be learned from and remembered.

This article was originally published on August 8, 2011.