Published Sep 26, 2024

'The Quality of Life': Consciousness and A.I.

How the exocomps teach us everything we need to know about A.I. consciousness.

StarTrek.com

Dr. Beverly Crusher defines life as "what enables plants and animals to consume food, derive energy from it, grow, adapt themselves to their surroundings, and reproduce." It's what she knows, or what she thinks to say, to Commander Data in "," the ninth episode from sixth season of .

"The Quality of Life"

StarTrek.com

Crusher does acknowledge that this answer feels inadequate, whether it's because an android colleague asked the question or in spite of it. Either way, it's more rote knowledge than hard qualifications. Fire, she tells Commander Data, is most definitely a chemical reaction. So are growing crystals. Fire and growing crystals check off several categories from the list. But what about viruses? Or Data, an individual who's programmed and built and very much living?

It's a brief conversation, but it establishes a few different ways that inorganic life can fit the definition of what it is to be "alive." In "The Quality of Life," Data, an artificial lifeform, is the one to test and define those boundaries.

"The Quality of Life"

StarTrek.com

In 2023, a collaboration of researchers published Consciousness in Artificial Intelligence: Insights from the Science of Consciousness.* It's dense and empirical for someone with an amateur (and cautious) interest in this type of technology, but it does nail down 14 "indicator properties," or criteria, that are positive signs of consciousness in artificial intelligence.

Note that being "conscious" is not "alive"; that’s a separate condition, and not easily answered when we're talking about exocomps, Commander Data, PaLM-E, or Transformer-based language models. This study, carried out by a group of 19 neuroscientists, computer scientists, and philosophers, is more interested in defining and organizing artificial consciousness.

Following a rewatch of "The Quality of Life," I realized that Data, the most conscious A.I. of all, uses many of the study's markers to argue in favor of the exocomps. They meet major criteria, like:

- Perceptual awareness: Check.

- Recurrent processing: Check.

- Predictive processing? Check.

- Integrated cognition? Check.

- Learning and adaptation? Check.

- Agency and action control? Check.

- Social interaction and theory of mind? Check.

- Higher-order thought? Check.

- Emotion and motivation? Check. .

"The Quality of Life"

StarTrek.com

I'll preface that my broad definitions of the study's categories are significantly boiled down. I'm not an expert in global workspace or attention schema theories, two of the six testing categories outlined in the study and ones that seem pretty critical to understanding A.I. consciousness. I'm someone diving in slowly to these ideas, probably because it feels better to confront doubts and questions you're personally having when it shows up in a TNG plot.

"The Quality of Life" confirms a bias I have about the likely future of A.I.. From what I've gathered, consciousness (partially) means forming an integrated thought and bringing that thought to attention. So, here's my thought: Or, a concern about a modern expectation that's frighteningly hard to undo — when does A.I. become conscious?

"The Quality of Life" takes a gentle, curious approach to this theme; it doesn't bring up lonesome dread like Her, or play up imaginative fears like I, Robot or The Terminator franchise. The exocomp looks a little… rudimentary, if not fairly cute.

But that doesn't reassure me. It's easy to feel distrust when there's a growing public resentment towards A.I., especially large, multi-modal language models that raise significant questions around authorship, job competitiveness, monetization, and the next phase of human thought. Look at the 2023 Writers Guild of America strike — one of the picketers' sticking points was to limit the use of Generative Pre-trained Transformer A.I. in creative storytelling. And then there was that eerie open letter asking to pause A.I. experimentation, signed by leading A.I. technologists, and published by the uncomfortably-named Future of Life Institute? You can't help but wonder if it's a warning to snuff out Prometheus' flame after he's razed half the forest.

Still, I think it's a decent idea to confront the question of A.I. consciousness even if we're not fully prepared (or willing) for the answer. Artificial intelligence as we contemporarily know it is nearly 75-years-old. Doesn't that mean it's had a long time to learn?

"The Quality of Life"

StarTrek.com

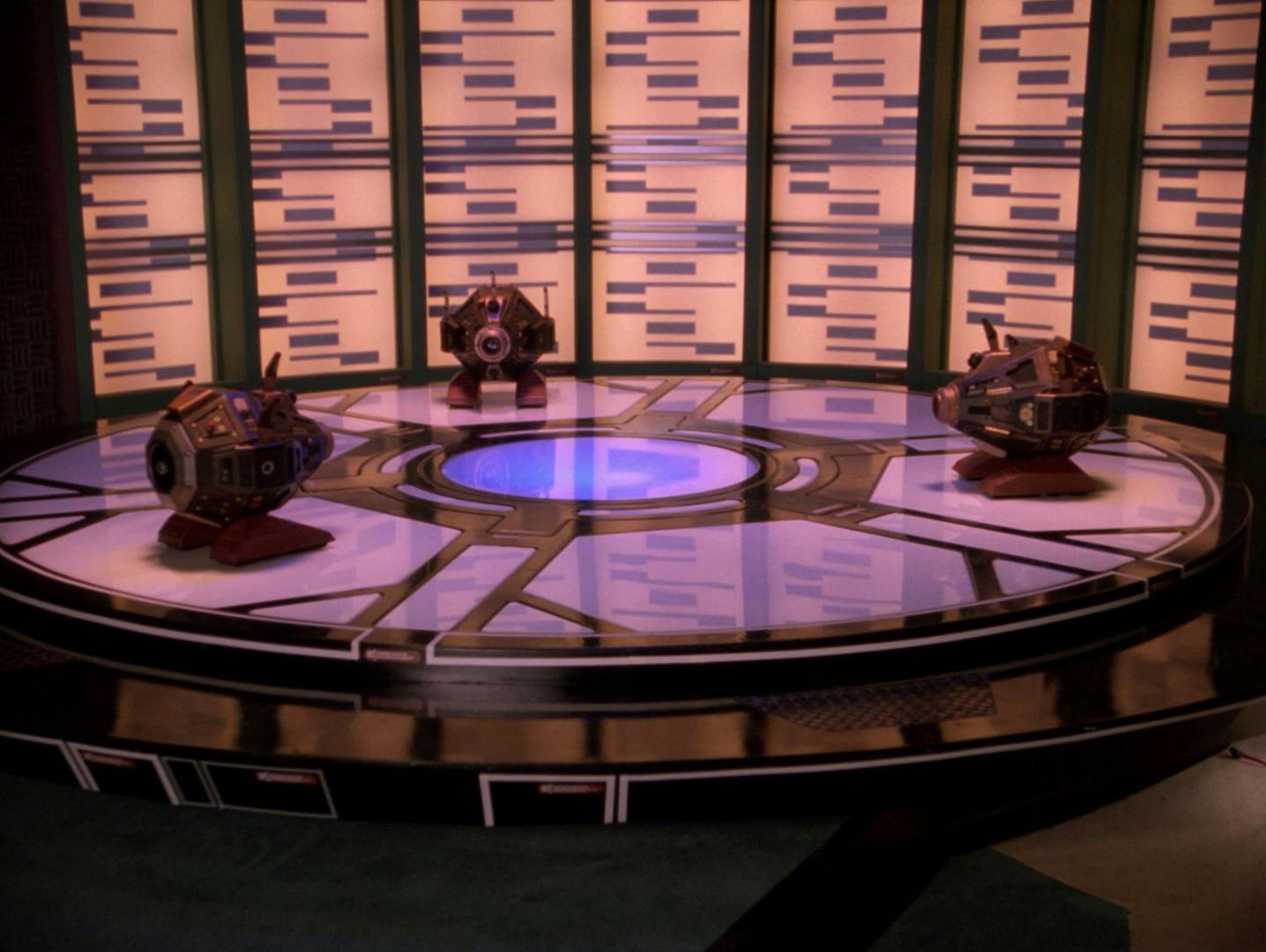

An adaptive bot built from a "common industrial servo mechanism," the exocomp is described as a repair and assessment tool. Their creator, Dr. Farallon, hopes to use them widely in her latest project which has captured Starfleet's attention.

Farallon is testing a particle fountain stream in orbit around Tyrus VIIA. Since it's a promising mining technology, Starfleet is eager to evaluate her results, and assigns the U.S.S. Enterprise-D to monitor her progress. Chief Engineer Geordi La Forge is directed to work alongside Farallon, mostly to prevent further delays on her so-far plagued project. In fact, just a few minutes after showing up at the Tyran station, La Forge witnesses one of the project's many setbacks, this time a power grid failure.

Rather than initiate a core shutdown and lose four months of work, Dr. Farallon programs one of her "exocomps" to enter an access tunnel and speedily repair the damage. Geordi is impressed; this little fix-it bot was successfully quick in locating and stabilizing the faulty grid component. Aboard the Enterprise, Dr. Farallon offers a further demo of the exocomp, far more interesting than this particle stream. Data is invited to observe.

"The Quality of Life"

StarTrek.com

Seeking out and classifying "living intelligence" is a well-tread theme in The Next Generation; the Enterprise is first and foremost on an exploratory mission. Often though, humanoid or non-human aliens are the "consciousness models" that the human audience reflects against. We make contrasts, draw a few comparisons, and use a subjective point of reference to apply intelligence to beings from other worlds. Sometimes, humanity's intelligence is the one under assessment; warp-capable cultures like the Q Continuum call into question the limitlessness of sentient experience. Still, what makes us conscious is rarely up for debate. Even when an extraterrestrial is a vapor cloud, sentient space debris, a candle ghost, or an ancient, enigmatic bio-ship on a lonely mission (""), we still understand these beings to be capable of thought and independent behavior.

But what about artificial life? We've accepted that even the most advanced synthetic beings are created to mimic, or fulfill, human thought patterns and behaviors. What if wanting to give an A.I. consciousness is a case of over-attribution, a point articulated on page 65 of this study? We do have a tendency to anthropomorphize or assign "human-like mental states to non-human systems." It explains our fixation with building androids in a human image, or making them capable of empathetic expressions like grimacing or painting.

That's what makes "The Quality of Life" so different. Data isn't testing the exocomps against human "agent bias." He's an artificial lifeform too. All the awareness exhibited by the exocomps is identified, then protected, by their own. Maybe in the exocomp Data sees the equivalent of an evolutionary predecessor, an infant A.I. in its early state of discovery. Or, maybe that's my "over-attribution" talking.

Regardless of Data's perception, his choice to preserve the exocomps isn't about "artificial" versus "organic." It's about "conscious" versus "unconscious."

"The Quality of Life"

StarTrek.com

The closing act of "The Quality of Life" focuses on Data's decision to save the exocomps, even at the cost of La Forge and Picard's lives. When her particle fountain suffers a radiation breach, Dr. Farallon suggests programming the exocomps to self-destruct in order to disrupt the matter stream. But this would require overwriting their command pathways, since they'd already demonstrated clear survival instincts. Data encourages Commander Riker to ask the exocomps to perform whatever solution they deem fit, giving them the choice to refuse to carry out the repair, or, self-sacrifice. Either way, the outcome's on their terms.

When asked by Picard why he would choose the exocomps over his colleagues, Data references back to "," the ninth episode in the second season, and the one where during a court martial hearing. While arguing that all sentient beings have the right to self-determination, Picard references Data's self-awareness and his vast intelligence. But consciousness, he argues, is unmeasurable.

I do think Picard misses the mark when he tells Data that advocating for the exocomps is the "most human decision" he's ever made. Based on what we now understand about artificial intelligence and its crossroads in consciousness, "human" isn't the right word; Data's decision is a conscious one.

"The Quality of Life"

StarTrek.com

* Consciousness in Artificial Intelligence: Insights from the Science of Consciousness authors include:

- Patrick Butlin, Future of Humanity Institute, University of Oxford

- Robert Long, Center for AI Safety

- Eric Elmoznino, University of Montreal and MILA - Quebec AI Institute

- Yoshua Bengio, University of Montreal and MILA - Quebec AI Institute

- Jonathan Birch, Centre for Philosophy of Natural and Social Science, London School of Economics and Political Science

- Axel Constant, School of Engineering and Informatics, The University of Sussex and Centre de Recherche en Ethique, University of Montreal

- George Deane, Department of Philosophy, University of Montreal

- Stephen M. Fleming, Department of Experimental Psychology and Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging, University College London

- Chris Frith, Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging, University College London and Institute of Philosophy, University of London

- Xu Ji, University of Montreal and MILA - Quebec AI Institute

- Ryota Kanai, Araya, Inc.

- Colin Klein, School of Philosophy, The Australian National University

- Grace Lindsay, Department of Psychology and Center for Data Science, New York University

- Matthias Michel, Center for Mind, Brain and Consciousness, New York University

- Liad Mudrik, School of Psychological Sciences and Sagol School of Neuroscience, Tel-Aviv University and CIFAR Program in Brain, Mind and Consciousness

- Megan A. K. Peters, Department of Cognitive Sciences, University of California, Irvine and CIFAR Program in Brain, Mind and Consciousness

- Eric Schwitzgebel, Department of Philosophy, University of California, Riverside

- Jonathan Simon, Department of Philosophy, University of Montreal

- Rufin VanRullen, Centre de Recherche Cerveau et Cognition, CNRS, Université de Toulouse