Published Oct 2, 2023

How Ben Sisko Wrestled With American History

Deep Space 9's captain, and Avery Brooks, never shied away from shining a light on American racism.

StarTrek.com

The world of Star Trek is filled with numerous references to American history. James T. Kirk’s reverence for Abraham Lincoln served as a subplot for episode “.” Tom Paris’ love of American popular culture from the 20th Century gave him and the crew of the starship Voyager numerous headaches thanks to holodeck malfunctions. However, Benjamin Sisko’s relationship to American history is the best example of the complicated story of the American people. ’s willingness to tackle this complexity is part not only of that show’s enduring legacy in pushing the boundaries of what Star Trek would talk about, but also of the larger cultural shift in the 1990s towards greater awareness of America’s history — warts and all.

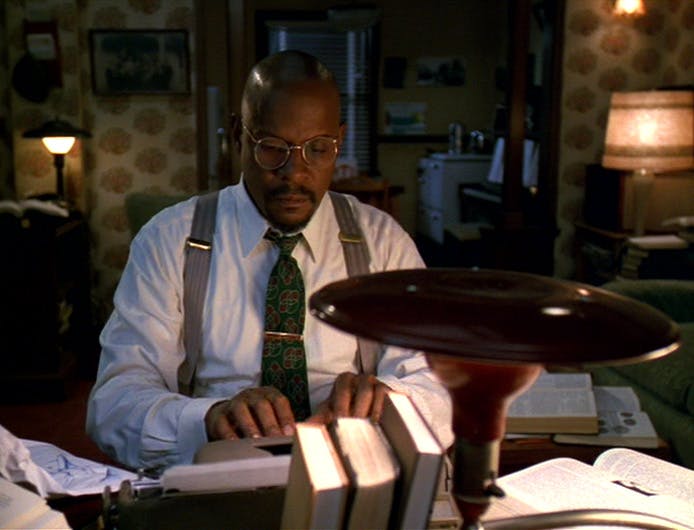

The episode “” uses the Prophets and fascination with their Emissary, Benjamin Sisko, to talk about the role of racism in 1950s America. The perspective offered in the episode is a look at life specifically as a Black writer. Benny Russell, the persona Sisko adopts in the episode — and, as it wears on, slowly begins to believe he is — represents the lost dream of Black science fiction fans and writers in the 1950s. Science fiction has always had a diverse fanbase, with some of the earliest science fiction fan clubs being formed in Harlem, New York. But Russell’s struggle to get his story published at Incredible Tales mirrors the real-life lack of diversity amongst most of the science fiction writing club of the 1950s.

Star Trek History: Far Beyond the Stars

But that isn’t to say Black Americans never attempted to write science fiction. W.E.B. Du Bois, the famed African American scholar, activist, and intellectual, wrote the science fiction short story “The Comet” for his 1920 collection Darkwater. Before that, the fantastical work by 19th Century Black Nationalist Martin Delany Black, or the Huts of Africa, dreamt of an independent African empire century before anyone wrote about the exploits of Wakanda. Russell’s story of a Black man in charge of a space station would have, in the 1950s, seemed more fantastical than the aliens he would have squared off against.

“You are the Dreamer…and the Dream.” A Preacher, appearing in the image of Ben Sisko’s father Joseph (and played by the legendary actor Brock Peters) tells this to Benny Russell during the climax of “Far Beyond the Stars.” To dream of a world free of racism animated many members of the Civil Rights Movement, which was occurring in the era Sisko dreamed himself to be in. It’s a reference to the “dream” Martin Luther King, Jr. referred to in his “I Have a Dream” speech— one that Sisko was likely familiar with.

"Far Beyond the Stars"

StarTrek.com

Sisko’s knowledge of 20th Century American history plays a role in the episode. Avery Brooks as director also shines through in the episode. Referring to it as his favorite episode, in interviews about his time on Deep Space Nine, Brooks said, “It was the most important moment for me in the entire seven years” the series ran. Where Star Trek normally deals with problems of racism, discrimination, and prejudice through the allegorical lens of alien races, what sets “Far Beyond the Stars” apart from those stories is its real-world setting — one that likely would have been familiar to Black American fans of Star Trek who came of age in the 1950s and 1960s.

The science fiction of the 1950s sometimes dealt with racism and prejudice via allegory. The most glaring example of how science fiction literature, in particular, tried to confront racism was via the company EC Comics. According to University of South Carolina professor Qiana Whitted, Entertaining Comics Group published stories about racism that directly challenged the world Benny Russell confronted. Publishing stories that included Black people as astronauts — during an era when NASA would soon be criticized for having no actual Black astronauts in the space program — shows that some science fiction writers in the 1950s attempted, with varying levels of success, to confront the limitations of the genre that Russell himself could not overcome.

"Far Beyond the Stars"

StarTrek.com

Sisko’s knowledge of American history also comes to be part of another episode of Deep Space Nine. “” hinges partly on Sisko’s knowledge of racism in 1960s Las Vegas. Where “Far Beyond the Stars” left Sisko with no choice but to confront racism in American history, “Badda-Bing, Badda-Bang” allows Sisko the opportunity to reject what he sees as a false, comforting vision of humanity’s past. Asked by Kasidy Yates, his soon-to-be wife, to join other members of crew to save hologram Vic Fontaine from 1960s-era mobsters harassing him on the holosuite, Sisko appears at best reluctant to go join the program. He argues, “We cannot ignore the truth about the past” about racism in Las Vegas, or America more broadly, in the 1960s.

Kasidy’s push-back on this question is interesting to note. She tells Captain Sisko, “Going to Vic’s won’t make us forget who we are or where we come from. It reminds us that we’re no longer bound by any limitations. Except the ones we impose on ourselves.” Kasidy reminds Sisko, and the audience, that the fantasies seen on the holosuites aren’t meant to be taken as real history — and, in fact, show us what could have been in a far better, freer world. Still, Sisko’s initial response to this holosuite program is not just him remembering what he has likely read and learned about American history in the past. Much of it also reflects his own experience with American racism in the 1950s, the era that “Far Beyond the Stars” portrays.

"Badda-Bing, Badda-Bang"

StarTrek.com

Ben Sisko’s reckoning with American history reflects a broader societal trend in real life with trying to come to terms with racism in American life. In the 1980s and 1990s, films such as Brother From Another Planet (1984), Malcolm X (1992), Glory (1989), and Do The Right Thing (1989), among others, tried to show how America’s complicated and painful relationship to Black history continued to shape the nation throughout its history.

Avery Brooks himself starred in a PBS production of the book Twelve Years a Slave in 1984, over 30 years before the big-budget Hollywood version. Brooks would later go on to play the iconic Hawk in Spencer for Hire and, more importantly in A Man Called Hawk, a short-lived spinoff series where Hawk deeply embraced Black history. For example, in the pilot episode Hawk rejoices at reading a copy of W.E.B. Du Bois’ Souls of Black Folk signed by the author himself. And Brooks also starred in American History X, a film that was made and released in 1998 near the end of Deep Space Nine’s run. There, he starred as a high school principal who teaches a white supremacist, played by Edward Norton, a version of American history that does not shy away from racism.

"Far Beyond the Stars"

StarTrek.com

Both Star Trek and Avery Brooks have dealt with racism in American history through trying to entertain and inform audiences, all at once. While this show’s relationship to racism in American history is but one example of that, we must always remember that Deep Space Nine pushed the boundaries of Star Trek in ways that many fans are still wrestling with today.