Published Dec 23, 2021

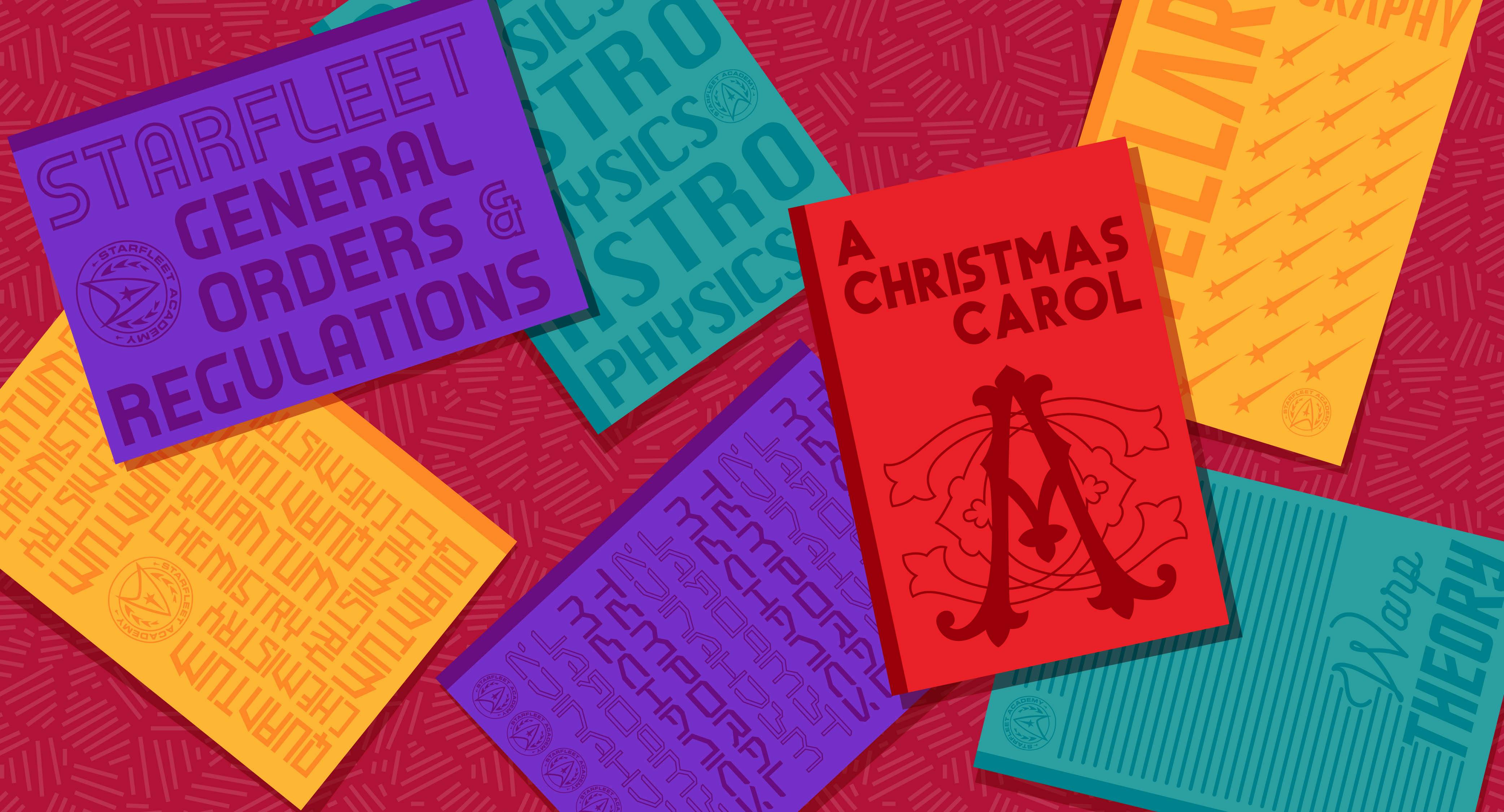

Why A Christmas Carol Is Required Reading at Starfleet Academy

Unsurprisingly, the answer has very little to do with Christmas!

StarTrek.com

They don’t celebrate Christmas on Star Trek. Though that fact never gets directly stated, it’s easy to infer from the fact that there’s never been a Christmas episode of Star Trek — we’ve never seen Quark attempt to steal Christmas, or Geordi and Data accidentally reenact “The Gift of the Magi” with Geordi selling his VISOR to buy Data a new poker table. Q has never purported to be Santa Claus. The utopian future of Trek is, by and large, a secular one, where the human characters acknowledge the myriad traditions of other cultures while honoring very few traditions of their own.

Which makes it all the more fascinating that the human characters on Star Trek all seem to be very familiar with the text, plot, and characters of Charles Dickens’ seminal holiday story, A Christmas Carol.

StarTrek.com

In the Next Generation episode “Devil’s Due,” Data performs the part of Scrooge in a holodeck recreation of the story, while Picard follows along and critiques Data’s ability to perform the part. The crew of the Enterprise tends to stick to well-known classics like Shakespeare and Sherlock Holmes, so it’s safe to say A Christmas Carol enjoys a similarly comfortable level of renown, and Picard seems intimately familiar with the source material (though he’s got nothing on Patrick Stewart, who has played the part of Scrooge in multiple one-man shows and one 1999 TV movie that remains my favorite version).

Patrick Stewart Reads From A Christmas Carol

In the first episode of Star Trek: Voyager, when Harry Kim tries to rationalize that Tom Paris isn’t that bad of a guy, since he confessed to the wrongdoing that landed him in jail, Tom snarks "the ghosts of those three dead officers came to me in the middle of the night and taught me the true meaning of Christmas.” Sarcasm doesn’t work if you have to explain it, so pretty clearly this is a common reference any human can be expected to get.

So why, in a society without Christmas, is A Christmas Carol so revered?

Written in a flurry in 1843, Dickens’ novella tells the story of Ebenezer Scrooge, a moneylender-bordering-on-loan-shark who gets turned aside from his penny-pinching ways when he is unexpectedly visited first by the ghost of his long-dead business partner, and then taken through his entire life by the Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Future. (The TNG finale “All Good Things…” follows the broad strokes of that plot, with Q standing in for all the ghosts). Emerging from his experience transformed, Scrooge goes forth invigorated with the Christmas spirit, giving money generously to the poor and taking a particular interest in the family of his employee, Bob Crachitt.

What makes this story so enduring — and what might, theoretically, make it so enduring for the characters on Star Trek — is that in message and morals this story aligns perfectly with the teachings and values of the Federation, and Star Trek as a whole.

StarTrek.com

It’s a surprisingly secular work; though the story revolves around a Christian holiday, very little mention is made of Biblical figures. The hell that Jacob Marley suffers bears very little resemblance to Christian theology; instead of being tormented in a fiery pit by Lucifer, Marley wanders the world forced to witness human suffering he is no longer in a position to alleviate, and human joy in which he can no longer share. These are messages that allow the story to resonate beyond the narrow confines of a religious holiday, and resonate with the crew of a Starfleet vessel:

"It is required of every man," the Ghost returned, "that the spirit within him should walk abroad among his fellow men, and travel far and wide; and if that spirit goes not forth in life, it is condemned to do so after death. It is doomed to wander through the world — oh, woe is me! — and witness what it cannot share, but might have shared on earth, and turned to happiness!"

The real villain of A Christmas Carol is capitalism itself. We see both the unhappy life of Scrooge, who is hoarding wealth, as well as all the people who could be saved if that wealth were instead shared. Scrooge, like Marley, is tormented not with the promise of physical torture in the afterlife, but the consequences of his own actions. No one will miss him when he’s dead, Tiny Tim will die from lack of access to food and medicine, and grifters will pawn the clothes he was supposed to be buried in. The story ends with a radical redistribution of wealth, with Scrooge giving food and money freely to the Crachitt family, and changing his draconian moneylending policies to something more just and equitable.

When the Ghost of Christmas Present admonishes Scrooge for the disregard he shows the poor and destitute it’s with the same righteous anger we’ve seen from any number of Trek characters:

“Will you decide what men shall live, what men shall die? It may be, that in the sight of Heaven, you are more worthless and less fit to live than millions like this poor man's child. Oh God! to hear the Insect on the leaf pronouncing on the too much life among his hungry brothers in the dust."

When A Christmas Carol originally came out, it captured a cultural resurgence in the celebration of Christmas. The holiday had been waning in British culture in the face of increased urbanization and industrialization, but a romanticization of old traditions like caroling, combined with newly-imported German traditions like the Christmas tree, captured the imaginations of the era. Dickens’ novel cemented those traditions, but also added a spin of his own: that Christmas was a time for giving freely, caring for the poor, and being generous not just with money, but also with your heart. Public welfare was a particular topic of interest for Dickens, and he used this work and the holiday to highlight the suffering of others, and the responsibilities we owe to one another as “fellow-passengers to the grave.”

StarTrek.com

There’s a reason that aboard Voyager, the Doctor gives A Christmas Carol to Seven of Nine as suggested reading: the book highlights not only the worst excesses of the human capacity for greed and cruelty, but also the ability for transformation in the human spirit. It’s a book that highlights where we’ve come from, but also the future that we could be going to - the future that, for the characters on Star Trek, we’ve reached.

I said at the beginning that we know the characters on Star Trek don’t celebrate Christmas because there are no Christmas episodes, but that may be because the characters don’t need to be reminded of lessons about tolerance, and good’s triumph over evil, and generosity, and personal betterment. Gene Roddenberry’s aspiration for the future was that those things would be a given. The characters on Star Trek may not celebrate Christmas, but that’s because they don’t need to: they embody the “Christmas spirit” as Dickens and Scrooge would have understood it year-round, no matter what the calendar - or stardate - says.

So if you want to commandeer the family TV on December 25th and stage a marathon of your favorite episodes, you can quite rightly inform them that you are, in fact, celebrating. Because when you get right down to it, every episode of Star Trek is a Christmas episode.

Sean Kelly (he/him) is a freelance writer based in St. Louis. He occasionally gets depressed that he’ll never know what raktajino tastes like.