Published May 26, 2021

Wayward Sons: How Worf Helps Me Navigate Adoption

“Are you the son of Mogh?" "Yes, I am."

StarTrek.com

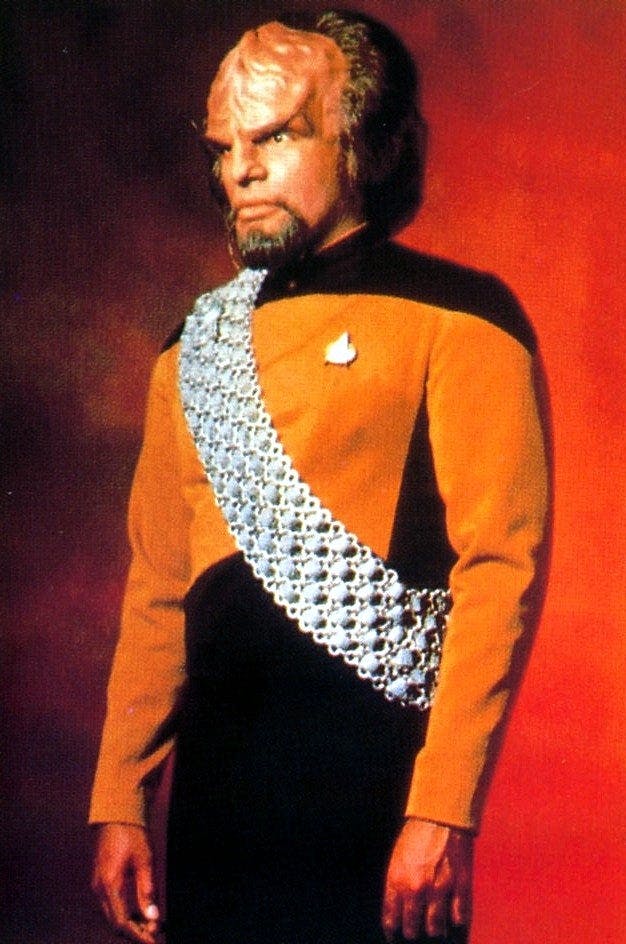

From his first appearances in Star Trek: The Next Generation, Worf is cast as an outsider. He’s the first Klingon in Starfleet, but even more than that, he is a Klingon orphan raised by Humans. He is different and that’s made clear from the beginning. In “Encounter at Farpoint'' Captain Picard orders Worf to take command of the Enterprise-D’s saucer section, to which Worf objects immediately: It’s against the Klingon way to abandon his commanding officer. Picard gives him a stern talking to on duty, and already we can see that Worf is out of place. Throughout the rest of TNG’s run and later, stationed on Deep Space Nine, Worf grows with and towards his Klingon heritage, eventually finding his own relationship with his dual heritages. And yet, his Klingonness is never really his own. Even in that first “Klingon vs Human'' interaction in “Encounter at Farpoint'' we see that Captain Picard is using Worf’s identity against him. Picard’s appeal to Worf’s duty goes beyond just that of a Starfleet officer. If Worf were to disobey, he would not just face a probable court martial, but he would be an example of a stereotypical “bad” Klingon in the eyes of those around him.

StarTrek.com

I, myself, am an adoptee. I was born in Cambodia and when I was 3 months old my mother left me in an orphanage where I was adopted 3 months later and was brought to the United States. Like Worf, I’ve spent most of my life trying to figure out what Cambodianness means to me, if and how it can coexist with my white, American upbringing. I’ve always identified myself with Worf, but what’s drawn me to Worf above the other “outsider” characters (Odo, Data, Spock, etc.) was the way his identity is informed and dictated by those around him. As a transracial adoptee, my identity is a series of choices I have made to balance — or not balance — what feel like two radically different sides of myself. I was raised and socialized in white suburbs, which shaped the way I saw the world and myself. I am fortunate enough that most people I encountered weren’t openly hostile or racist towards me, but I also have a vivid memory of looking into the mirror by the front door and knowing that I looked “wrong.” For most of my life, I chose my adoptive side. When I would make attempts to learn about or connect with my Cambodian past, it felt artificial at best, or at worst, dishonest and ungrateful. The Khmer images and items I had felt like tokens that might as well have been from the Gamma Quadrant. Certainly, at least, they didn’t represent me. Over time, I’ve come to embrace more of my heritage through small items like jewellery, and using the name my mother gave me, but it has been a long and intensely personal process to reach that point.

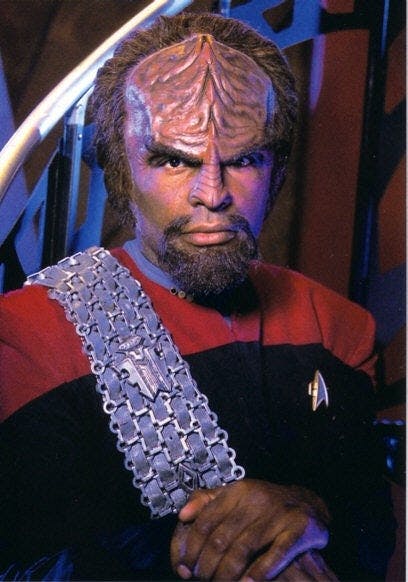

Pure Klingon joy and the ability to just exist are rare things for Worf. His triumphs are often framed through the lens of his two identities. His abilities as a tactical officer are often implied to be linked to (if not resulting from) his Klingonness. Throughout Trek, the dominant narrative of the Klingon culture is one of ancient glory, exemplified through the belief in Kahless, contrasted with a recent history of bloody conflict. Cambodian culture is seen through a similar lense. On one hand, the ruins of the Khmer Empire, especially the Angkor Wat complex, spring to mind. On the other, the genocide of the mid 20th Century is always present. To exist and be joyous in Khmer identity, then, is an act of liberation, just as Worf’s pride in his bat’leth victory liberates him from being viewed by his peers solely as the representative of an old enemy who has now been civilized.

StarTrek.com

Being made to be a representative of a community, through no real actions of your own, is something I can relate to deeply. I’m all too familiar with the experience of meeting a new person, only to find out they want to tell me about their backpacking trip through Southeast Asia. Cool, I guess. People tell me how they were warned about leaving the paths for fear of landmines and how beautiful they found the landscape in the same breath because, at the bottom line, they are one in the same. It throws my perception of my own homeland into flux, alongside my entire concept of identity. And yet, through Worf, I’ve seen a character who faces similar struggles: alienation both from himself, and from two cultures he would like to call his own in different ways. Worf’s lifelong process of defining and accepting himself, fully and authentically continues to be an inspiration for myself as I work through my anxieties and hopes around my own identity, and what it means to be me.

Matthew (they/he) is a recent McGill University graduate with a BA in Religious Studies and Classics, now preparing to explore the final frontier (the future) and hoping to continue their writing and research. Follow them on twitter at @sadmattyh.