Published Oct 29, 2019

Vintage Star Trek Novels Made Me a Better Reader and Writer

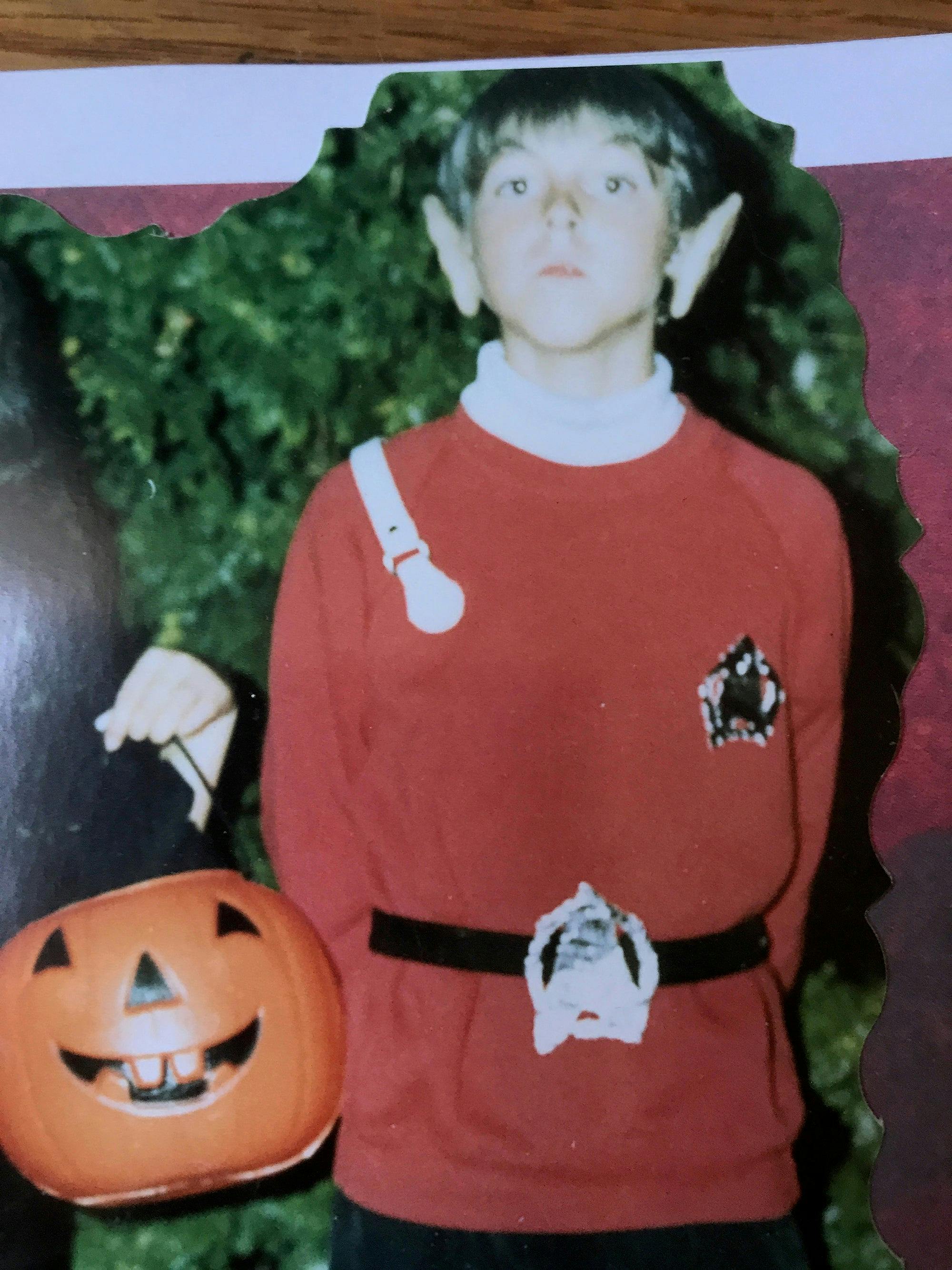

I was shy and a little withdrawn but the characters of Trek were reliable friends who I could always count on.

StarTrek.com

I’m not even sure why my 4th grade teacher allowed an 11-year-old to line their classroom desk with nearly 20 books, but I do remember my great barrier of Star Trek novels made me feel safe. From the years 1989-1995, roughly from 8-years-old to my early tweens, probably 80 percent of what I read for pleasure were Star Trek novels. At the time, my teachers and parents were on yellow alert: Did I need more variety in my reading? Was I ever going to read anything other Star Trek books?

Not only was everyone’s fear unfounded — I’ve read and enjoyed everything from Margaret Atwood novels to mysteries written by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar since then — I’m now also certain that burying myself in Star Trek novels was ridiculously good for me. Reading Star Trek novels as a child in the ‘80s and ‘90s not only made me a better reader and writer as an adult, it also meant that I side-stepped all kinds of sexist traps prevalent in, what was then, mainstream fiction for kids.

StarTrek.com

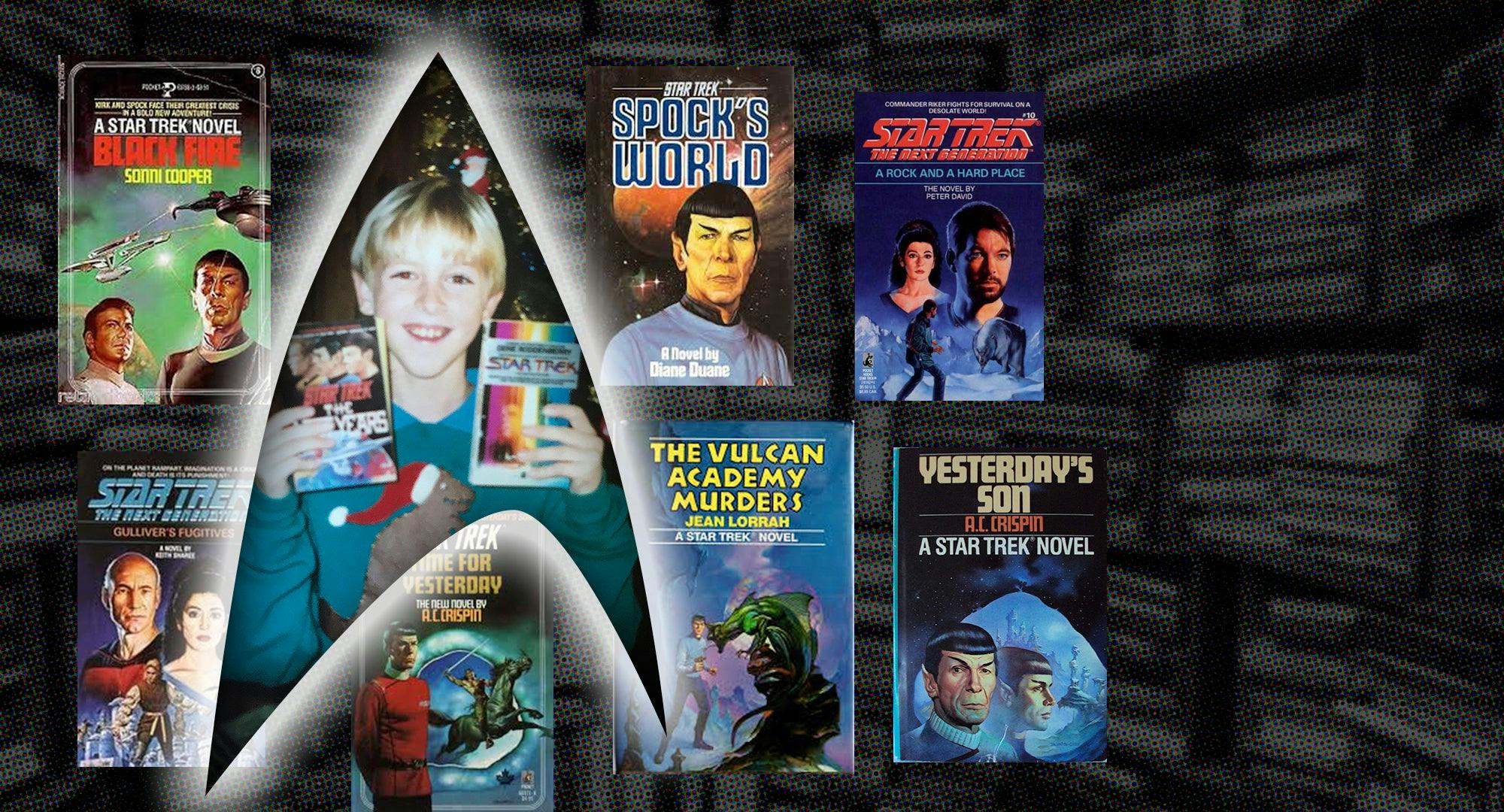

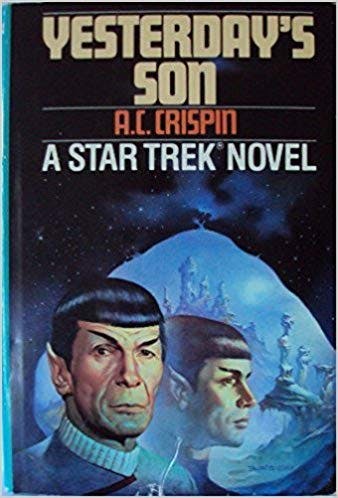

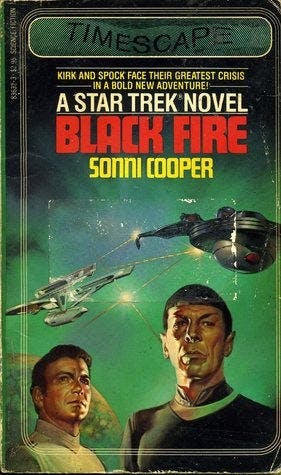

If you asked me to name my favorite author at 11-years-old, I would have said unequivocally that my favorite author was A.C. Crispin, author of the novel Yesterday’s Son. If I had to name a second favorite author, I would have probably said Sonni Cooper, the author of Black Fire. Flipping through these Trek books now, you’ll discover that they are just a scooch racier than your average episode of the original Star Trek. In Black Fire, Spock becomes a smooth space pirate, and in Yesterday’s Son, he discovers he has an illegitimate son — with the endlessly cool name of “Zar” — living in the distant past on the planet Sarpeidon. What both of these books had common is they dealt with Spock as a sexual entity, and both of them, with their initial only first name credits, were written by women.

The idea that my favorite authors as a young boy were women, was to me at the time, just a given. And that’s because, I think, the Trek novels of the ‘80s and ‘90s (regardless of the gender of the author) tended to have a non-gendered approach to their narratives. I mean, I freaking loved a book called A Rock and a Hard Place by Peter David in which Riker basically fights mutant snow wolves and the whole thing is like TNG-meets-Gary-Paulson’s-Hatchet . But even the male-centric Trek novels I adored weren’t macho or regressive. These books contained the same progressive pathos of the shows but made you think about the characters in a more multidimensional light.

StarTrek.com

In other words, the novel versions of Spock, Riker and Data are infinitely better for kids than, say, the Hardy Boys, who are the kids of kids whose social awareness is closer to racist Johnny Quest than anything else. To be clear, the Star Trek novels I read in the ‘80s and ‘90s were not sexy fanfiction in which Kirk and Spock made-out or Data was fully-functional. These were the real-deal licensed Star Trek novels that were totally approved. They weren’t canon at all, but when you’re a little kid, the idea of what does and doesn’t count in the overall “real” story of Star Trek hardly counts. That wasn’t their appeal anyway. They were great because the books also offered something to a fan that TV shows never could: They let you get inside the heads of your favorite characters.

For kids on the verge of puberty, the character of Spock is great from the outside, but arguably even better from within. Crispin’s Yesterday’s Son and its sequel Time For Yesterday didn’t present Spock’s feelings in a sort of cagey way; for the most part, these feelings are right there on the page for the reader to understand. When Spock learns of a cave painting that depicts the face of his son, Crispin lets us into his mind: “As I sit in the solitude of my cabin, I know I must begin considering precisely what I should do about the face on the wall of the cave.” There’s a familiar Sherlock Holmes-ish air to Spock’s internal thinking, and the fact we get that peak into his mind at all is a treat.

But there’s another humanizing moment, too. When Spock seeks advice from T’Pau, we get a telling moment of inner-nervousness from Spock: “Spock realized he had been holding his breath. The worst was over.” In the series and the films, you never really got this sense of Spock; the Spock who held his breath in tough situations.

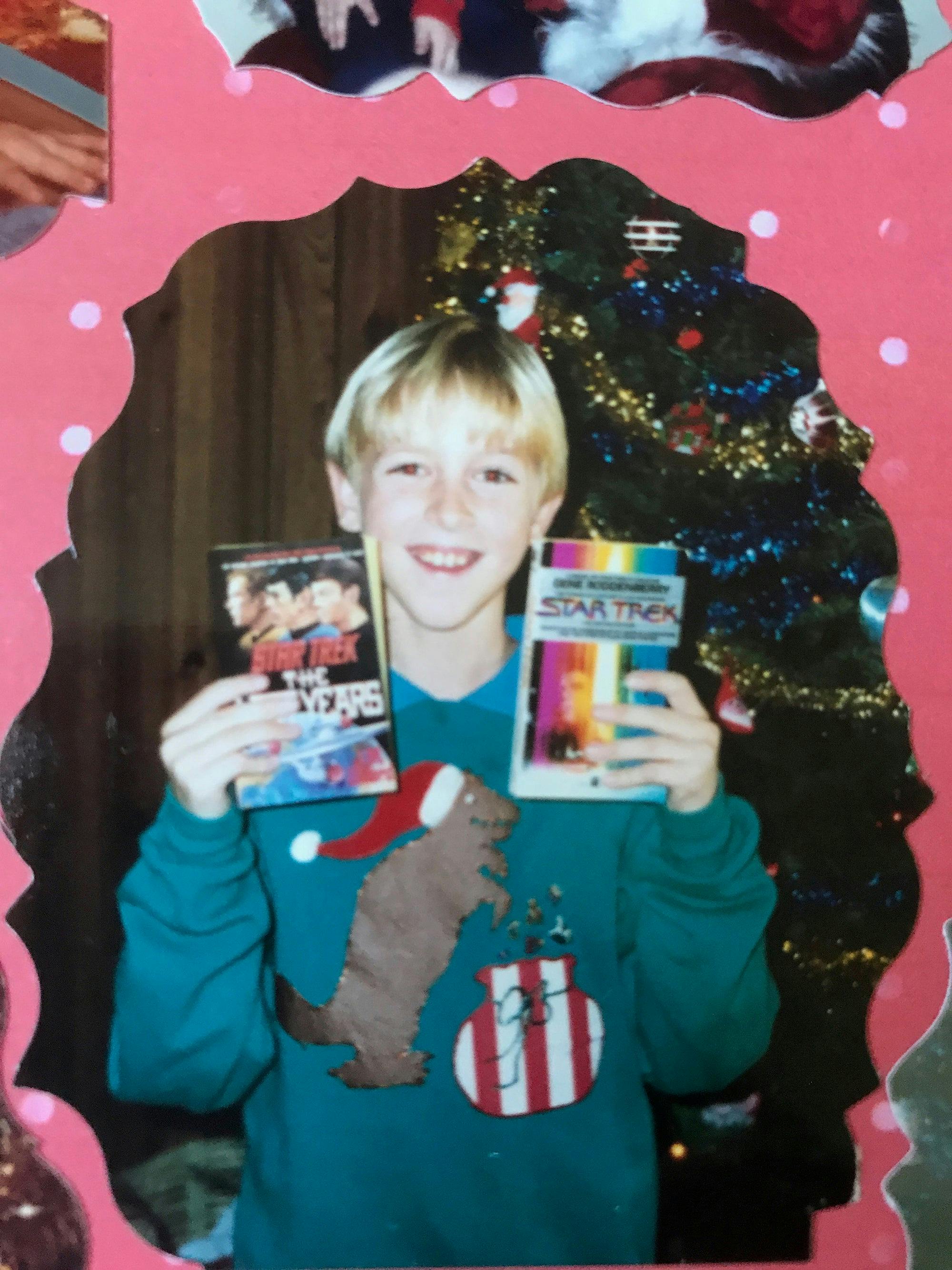

Ryan Britt

In Jean Lorrah’s The Vulcan Academy Murders, this notion of a character’s interior life is particularly interesting because we’re allowed inside Sarek’s mind for nearly the entire novel, which includes quite a bit about his love for his wife, Amanda Grayson. When I saw the Discovery season two episode “Lethe”, in which Michael Burnham enters Sarek’s mind, I immediately wanted to revisit the mind of Sarek as I remembered it in The Vulcan Academy Murders. To my pleasant surprise, it was just as easy to read the novel in 2017, picturing James Frain as Sarek, as it was to read it in the late ‘80s seeing only Mark Lenard in your mind’s eye. And, just like Michael Burnham was gifted Alice in Wonderland by her mother, Star Trek novels were also good gateways to other books.

In Christmas of 1990, I found The Next Generation novel Gulliver’s Fugitives stuffed in my stocking, a moment I will hardly forget, mostly because at nine, I wasn’t totally sure how to pronounce the word “fugitives” and I had no idea who this Guillver person was. Could they have been a Star Trek character I’d never heard of? Maybe there was an episode I’d missed? But, the premise of this novel, written by Keith Sharee, turned out to be much more interesting than a random space adventure. In the book, the crew of the Enterprise-D hits up a planet called Rampart, a place where it’s illegal to read fiction. This premise is so deliciously and purely Star Trek, I sometimes forget it wasn’t an actual episode of TNG in the ‘90s. And through this novel, I was introduced to all sorts of other books; the titular Gulliver as created by Jonathan Swift of course, but also Leopold Bloom of James Joyce’s Ulysses.

Ryan Britt

Later, I would learn that Gulliver’s Fugitives was a kind of mash-up of 1984 and Fahrenheit 451 combined with Next Generation characters, but, as I’ve grown up as a writer, the fact that this book was even published astonishes me because it’s both so thoughtful and so strange. When I think about all the Trek books I read as a kid, the ones that stuck with me, the ones I have revisited as an adult all shared one trait in common: They weren’t safe. Yesterday’s Son challenged what you knew about Spock’s basic character, The Vulcan Academy Murders was saturated in raw Vulcan feelings, and in Rock and a Hard Place, well, Riker almost gets eaten by a wolf. The point is, nearly every time, Star Trek novels weren’t comfort food. These authors did — and still do — take huge chances with beloved characters and situations.

Being shy and a little withdrawn is probably why I constructed a wall of paperback books on my desk in 4th grade. But, like a lot of fans, I also felt like the characters of Trek were reliable friends that I could always count on. Seeing Spock’s face on the cover of Diane Duane’s Spock’s World or seeing Picard’s steely gaze on Gulliver’s Fugitives probably helped me through more than one hard day. But, the paradox of these books is that as comforting as they were to look at, the real power they held was the absolute over-the-top riskiness of what was inside. One of my happiest childhood memories was browsing for a new Star Trek novel in a Waldenbooks and wondering if, through some kind of holodeck simulation, the books had been programmed to be specifically written for me. It was hard for me as a child to believe books could be that entertaining; it had to be some kind of trick!

But of course, many serious readers and writers start their love affair with books in exactly the same way: the sheer awe of realizing the infinite diversity and infinite combinations contained on some ordinary paper held together by an extremely slick cover. With Star Trek novels, you could judge a book by its cover, and still be surprised. Which, in a way might be a good explanation for why the franchise has lasted so long. Every installment of Star Trek is like a beautiful book on the shelf; familiar, well crafted and sturdy. But what’s inside is somehow, always a little different.

Ryan Britt's (he/him) essays and journalism have appeared in Tor.com, Inverse, Den of Geek!, SyFy Wire, and elsewhere. He is the author of the 2015 essay collection Luke Skywalker Can't Read. He lives in Portland, Maine, with his wife and daughter.