Published Apr 20, 2022

Star Trek Helped Me Find Pride in Being a Queer Man in STEM

"Star Trek nourished each identity - Asian, Queer, and STEM-focused - and helped bring them together."

StarTrek.com

This article was originally published on June 21, 2019

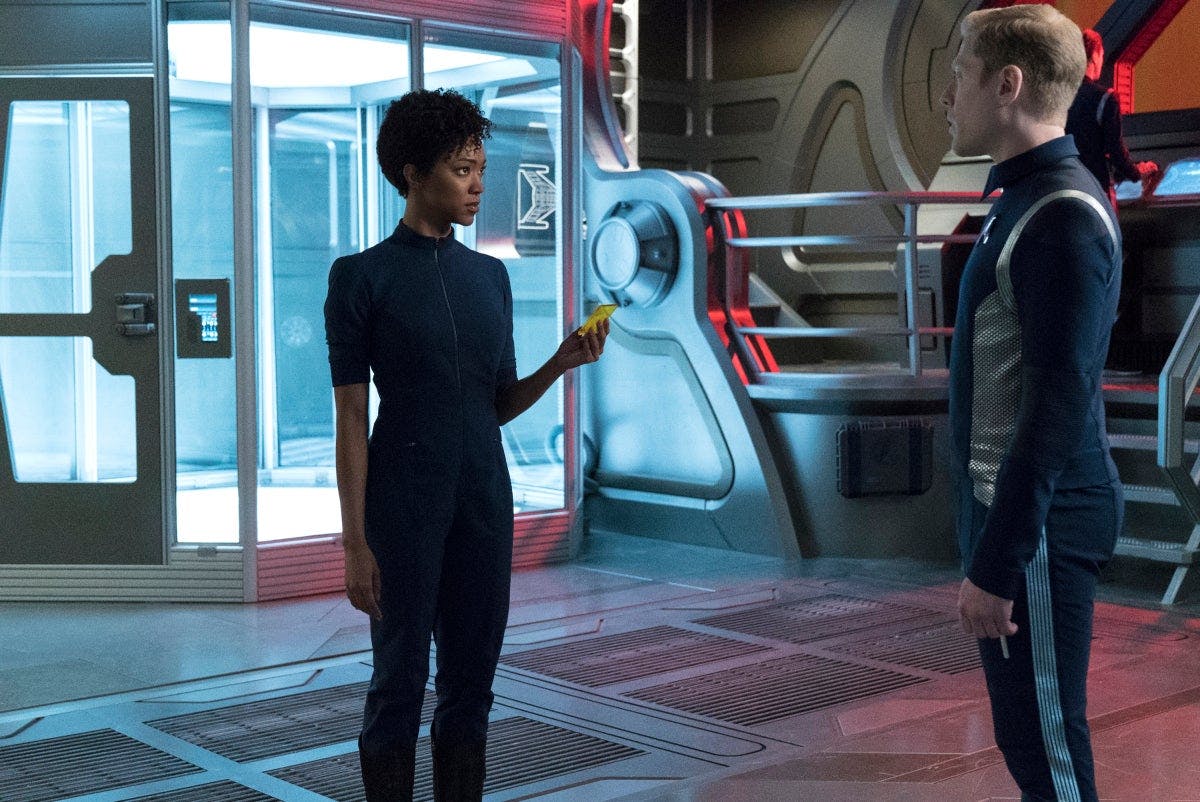

When Michael Burnham meets Paul Stamets, in the Star Trek: Discovery episode "Context is for Kings," the chief engineer is venting his frustration at the U.S.S. Discovery's militaristic shift from a scientific vessel. "I became an astromycologist because of awe," Stamets tells her. "Awe at the miracle of life."

At the age of seven or eight, I couldn't have phrased my love of science that eloquently, but I felt it. I spent afternoons reading about the anatomy of insects (head, thorax, and abdomen) and the water cycle, enthralled by the colorful illustrations within a series of books my parents had bought me. I wanted to understand the miracle of life desperately. I was a bright, but socially awkward child, the kind of child who didn't know the right things to say or do in groups. I had a sense that I was just a bit off, unable to connect with people in a way that appeared effortless to others. Often feeling lonely, science — seemingly reliable and endlessly complex — became a steadfast companion, something I could rely on to fill the hours.

StarTrek.com

Looking back, I knew I was different, but couldn't articulate how: it would take decades to process how my queerness, my Asianness, and my curiosity for STEM would define me, but also Other-ed me. The idea of the "Asian nerd" is a crushing stereotype because it takes a strength and curdles it into a weakness. What drew praise from adults drew venom from other children. I had to navigate these identities — queer, nerdy, Asian — sometimes individually, and eventually in concert with one another. But I always found that Star Trek has nourished each identity, and helped bring them together.

One of my treasured memories was watching The Next Generation on the couch, beside my mother. She'd been a fan of TOS, which she watched as a child living in Montreal. I loved television as an escape to worlds I might one day get to inhabit myself, and every week, I not only enjoyed the novel environments the U.S.S. Enterprise explored, but also a society that strove for logic and reason to take precedence.

Traveling with Captain Picard and his crew was an hour-long reprieve from the bullying I received at school. Although the show was set in the future, I couldn't help imagining one day being in Starfleet, where I might be welcomed. I became interested in astronomy, and spent afternoons drawing and redrawing the solar system while I begged my parents to take me to the planetarium. Every night I fell asleep to the faint fluorescence of the glow and the dark stars and planets I’d glued to my bedroom walls. I wanted to live amongst the stars.

StarTrek.com

Imagining myself on a starship was easy; the crew of the Enterprise looked more like my neighborhood in Toronto than most television shows, a mosaic of men and women from countries around the world. The additions of Rosalind Chao and Patti Yasutake as recurring cast members in the fourth season of TNG thrilled me: here were women who looked like my family members making important contributions to the Star Trek universe.

My passion for the sciences continued in adulthood and led me to an undergraduate degree in biomedical engineering. I marveled as professors talked about regenerative medicine, such as cardiac patches derived from pluripotent stem cells. Surrounded by a classroom of multicultural students that felt like the Starfleet Academy, I began drawing throughlines from what I was learning to a Star Trek-like future of dermal and vascular regenerators.

After graduation, I worked as a molecular biologist for a startup housed in a university that aimed to improve the lives of patients with significant orthopedic programs by building organic implants to replace the cartilage that wears down between joints. I was surrounded by people interested in research, and I was proud that I, even in the smallest of ways, got to contribute to the body of knowledge that could do good.

And yet I didn’t always feel welcome in academia. There has been a longstanding tension between the scientific and queer community, the former having used faulty research to justify labeling the latter as depraved, ill, and malevolent. (Sadly, this was not unique: bad science has been used to justify diminishing women, people of color, and other underrepresented groups.) Although many in science are inclusive and accepting, the overwhelming atmosphere of intolerance is enough to keep some researchers in the closet in fear of jeopardizing funding and career progression.

In my second year on the job, during the fall of 2005, George Takei came out publicly. It had never occurred to me that the iconic actor behind Sulu might identify as gay. As a child, I'd learned to believe that I was aberrant and that my desire was a statistical blip. I internalized the homophobia that told me that being myself was wrong, and perhaps it’d be better to not exist at all. But in my twenties, I realized that the stories we're told are shaped by the era they were written in, and Takei coming out showed how many hid in plain sight. Empathy is a powerful force, and when someone you know and love comes out, it can change minds: Now, so many fans of the beloved show would know someone from the world they loved who was out.

Suzi Pratt / Getty

A decade later, I similarly cheered the decision to feature John Cho’s Sulu with a husband in Star Trek Beyond — especially one of Asian descent. The moment is brief but surreal: five decades after the debut of Star Trek, I could see someone like me have their story played out without whispers, without codes. That excitement carries through, as I watch the interracial queer relationship on Discovery develop between Anthony Rapp’s Stamets and Wilson Cruz’s Dr. Hugh Culber.

Being different is both special and isolating all at once; but as RuPaul says: If you can't love yourself, how in the hell you gonna love somebody else? For me, it's still a continuing process, but I don't think I'd be as far along without Star Trek in my life.

We have to persevere to find our tribes — people who can come from many different backgrounds and yet connect with us in fundamental ways. With the help of organizations like the National Organization of Gay and Lesbian Scientists and Technical Professionals. I found mine within the many LGBTQ scientists who have changed this world, including Sally Ride, Alan Turing, and Lynn Conway. I’m excited by new faces like Emma Haruka Imao, who calculated pi to a record-breaking 31 trillion digits, and all of the research finally being done on queers in the STEM sciences.

More than anything, I’ve become more proud of my curiosity for how things work. And, much like Paul Stamets, I’m still in awe of the miracle of life — no matter what form it takes.

Jaime Woo (he/him) is a Toronto-based writer whose work has appeared in the Advocate, Globe and Mail, and Hazlitt. His book, Meet Grindr, an exploration of how the app influenced gay culture, was shortlisted for the Lambda Literary Award. He can be found at @jaimewoo on Twitter.

Star Trek: Discovery currently streams exclusively on Paramount+ in the U.S. Internationally, the series is available on Paramount+ in Australia, Latin America and the Nordics, and on Pluto TV in Austria, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Switzerland and the United Kingdom on the Pluto TV Sci-Fi channel. In Canada, it airs on Bell Media’s CTV Sci-Fi Channel and streams on Crave. Star Trek: Discovery is distributed by ViacomCBS Global Distribution Group.