Published Nov 5, 2019

How Modern Surgical Tech is Approaching Star Trek's Future

The PIRL Scalpel may not be the final frontier in surgery, but it's pretty close.

StarTrek.com

In every iteration of Star Trek, from The Original Series to Discovery, there are always a few scenes where a medical officer whips out a tricorder or dermal regenerator, waves it over an injured crew member, and fixes up their injuries without leaving a trace.

This sort of medical care might seem like something that could only happen in the distant future — if it could happen at all — but new developments in medical laser technology by a team led by University of Toronto professor Dr. R.J. Dwayne Miller are moving some of what we see on screen away from science fiction and towards science fact.

“I think the thing that’s interesting about Star Trek is that the writers — and all sci-fi writers — let their imaginations go wild and ask ‘wouldn’t it be great if…?’” said Dr. Miller, who grew up watching the show. “And science, eventually, by some circuitous route, sometimes does find things that look very similar to what they imagined.”

ESU Lab

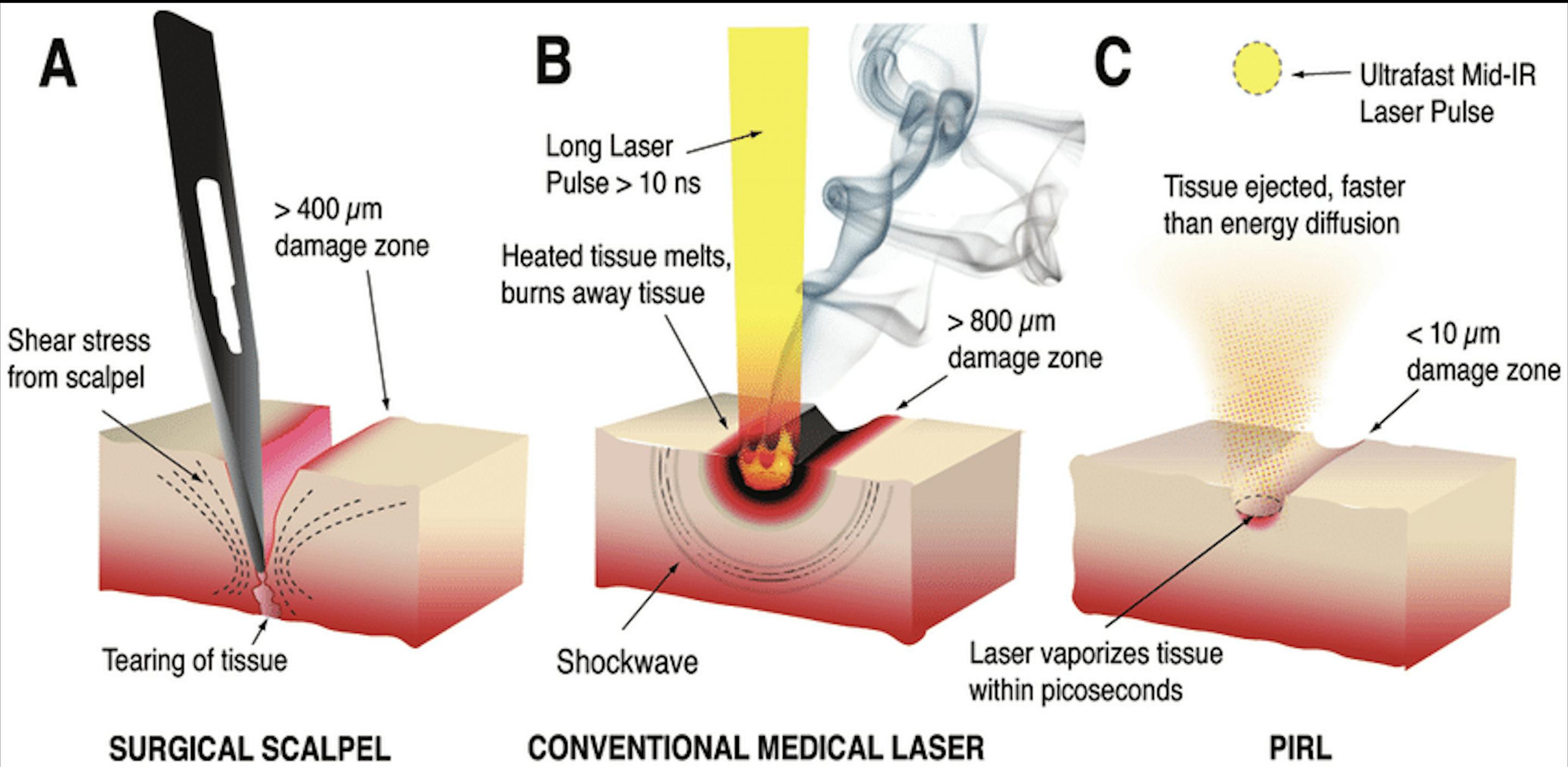

When Theodore Maiman successfully fired the first laser in 1960, just six years before Star Trek first aired, people almost immediately recognized its potential uses as a surgical tool. In theory, by focusing energy towards a specific place, lasers should allow a surgeon to make precise cuts even in hard-to-reach areas of the body. But there were significant downsides to this approach.

“The problem isn’t getting energy down to the dimension of a single cell,” Dr. Miller explained. “The problem is confining energy. You put the energy in, and what would happen is that it would thermally diffuse. The temperature of the adjacent tissue would get above the combustion point, and you would get horrific burning.”

On top of that, there was the problem of cavitation, also known as 'bubble collapse' — lasers cause specific areas of tissue to undergo phase transitions, turning them from a solid to a liquid to a gas. Dangerous bubbles can form and spread during this process.

“Think about boiling a pot of water,” Dr. Miller said. “Next time you do this, look at the bottom of the pot. You’re going to see there’s little nucleation sites everywhere — bubbles grow and grow and then they violently collapse. That’s what happened when you used lasers for surgery … [I’ve seen surgeries where] cavitation shockwaves led to collateral damage away from the cuts.”

Since the 1980s, Dr. Miller has been trying to figure out a way around these problems. Armed with new discoveries that his lab made over more than a decade about the atomic and molecular structure of water, he posed the question: what would happen if you had a laser that fired extremely high-energy pulses, cutting so quickly and for such a brief time that bubbles wouldn’t form, and the surrounding tissue wouldn’t burn?’

So, he and his team built that laser, called the Picosecond InfraRed (PIRL) scalpel.

“The very first time we used it was just on skin tissue,” he said. “[For comparison] when you do surgery with a conventional laser, you see smoke, it looks horrible, you can see massive damage where you’re cutting. When you look at our laser, it’s just melting away at the tissue. You don’t see any smoke. It looks like you’re breathing into cold air.”

The PIRL scalpel also makes it possible to do scar-free surgery — if handled properly, once the cuts are healed, they are totally invisible.

ResearchGate

“When you would watch Star Trek, they would seemingly solve different things and instantly heal injuries,” Dr. Miller said. “Well certainly, now we can cut at that ultimate limit [of precision], and the healing, if you do bonding with bio-compatible glues, would literally look like the Star Trek thing. Actual scar-free healing takes time. But if you hold it and glue it, it would look — from a visual perspective — like it healed instantly.”

Surprisingly, scent was one of the more interesting developments to come out of the invention of this new tool. Dr. Miller’s laser scalpel allows doctors to actually smell the difference between different types of tissue as they cut, whereas with previous tools you could only smell the burning. This could have major implications for how surgeons work in the future, warning them when they’ve moved too far off track and even signaling the difference between healthy and diseased tissue.

“It turns out that the water is perfect at ejecting entire protein complexes into the gas phase, and we have a complete signature of what is being cut,” Dr. Miller explained. “Now, you’re talking about turning any surgeon into a super-surgeon, because you’re basically getting a barcode for what tissue is being cut.”

While the PIRL scalpel might well make modern-day hospital operating rooms look and function a lot more like Sickbay on the Enterprise, Dr. Miller has no illusions about the glamor (or lack thereof) of the years of research that brought him and his team to this point. Still, he says, it has all been worth it.

“Science is not all ‘eureka’ moments and fun and games,” he said. “It can be frustrating. You have to have a deep-seated drive to solve a problem, and maybe you have to be a little bit nuts to do it. It’s competitive; it’s a contact sport. Peer review is rigorous, and you have to respect the process. Science takes a lot of hard work. It doesn’t work the way you always think – and thank goodness, because otherwise we’d already know the outcome. And the reward is in the end – you get to go to a very beautiful place where nobody else has been. We get to go where no one has gone before.”

And Dr. Miller had a few words of encouragement for scientists who are currently embarking on their own journeys of discovery.

“You never know – by definition – where it’s going to go,” he said. “But, whatever the voyage, it’s going to be beautiful.”

Julia Peterson (she/her) is a queer Jewish journalist currently based in Regina, Saskatchewan. She also writes for INK Magazine, The Carillon, and Reading in Translation, and would give just about anything to have a pet tribble. Find her on Twitter @hark_a_julia.