Published Jun 9, 2023

How Star Trek V: The Final Frontier Made Me a Nicer Kid (and Better Person)

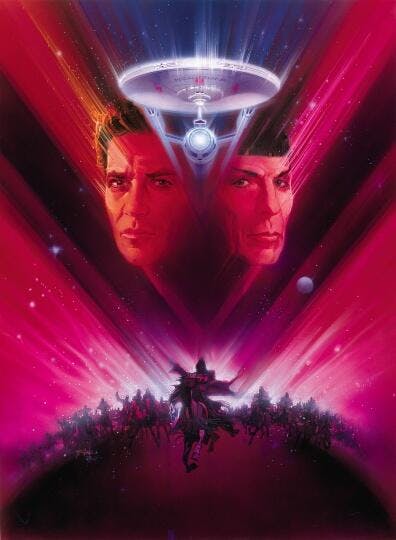

The 1989 film deserves more credit.

StarTrek.com

The idea that odd-numbered Star Trek movies are bad is a myth.

is good. No one nice actually thinks that Star Trek XI — better known as the J.J. Abrams reboot — is bad. And yes, , is in my book, a very good Star Trek movie; if only because it taught me, as a child, to be way more tolerant of the beliefs of others.

Star Trek V: The Final Frontier

StarTrek.com

In the canon of Star Trek, stories about religious differences are actually rare, which is why — 30 years ago, in the summer of 1989 — the Enterprise’s brush with organized religion was an important shock for an 8-year-old atheist kid.

I was a child who liked to catalog the things I watched (I wrote a recap of the finale “” in my 5th grade diary), but I don’t think I started to become critical of those things until my early teens. Star Trek was just Star Trek to me, and I could no more dislike one part of it than I could be mad about one of my cat’s paws. It was all part of the same animal to me, and because my parents were old-school fans who watched in the '60s and '70s, the TOS crew held a certain religious quality in our decidedly godless home.

"New Eden"

StarTrek.com

Though we lived across the street from a Lutheran church that we only dared to enter when it was time to vote, as a child, my relationship with religion was exactly like Michael Burnham’s experience of entering that church in the episode “New Eden.” To me, a church was a bizarre, alien place. And I, more often than not, found myself behaving like Spock or Burnham, looking for the empirical truth behind the spiritual myths.

Growing up, organized religion was everywhere — Mormons, Catholics, Jews, and Muslims made up not only people in my neighborhood, but also my friend groups. Still, because I was raised agnostic, I basically never went inside of a church as a child. For that reason, people who did go to church seemed weird to me.

"Where No Man Has Gone Before"

StarTrek.com

For the most part, my love of all things ‘60s Star Trek tended to reinforce the idea that churches — or things that claimed to be houses of God — were likely deceitful places. If you didn’t know anything about what Captain Kirk’s job really was on TOS, you might be shocked to discover that in several episodes he’s basically a false-god-unmasker.

Now, I’m not saying Kirk, Spock, and Bones are the Scooby-Doo Gang, and all those evil god-computers in TOS are like a muttering old men, bemoaning the existence of these “meddling kids” from Starfleet but I think you get the point. In The Original Series, the crew of the Enterprise beats back the machinations of false gods in “The Return of the Archons,” “The Apple,” “For the World Is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky,” “Who Mourns for Adonais?,” and famously, in Kirk and Spock’s first adventure; “Where No Man Has Gone Before.”

Behind-the-scenes of Star Trek V: The Final Frontier

StarTrek.com

And, at a glance, Star Trek V: The Final Frontier — famously directed by William Shatner himself (and based on a story he co-developed) — feels very much in line with Captain Kirk’s false-god busting from The Original Series. If you squint a certain way, Kirk uttering, “What does God need with a starship?” isn’t too different than he and Spock blasting the fake-god computer in “The Apple,” or even, destroying the war-calculating machines in “A Taste of Armageddon.”

After several films of middle-aged soul-searching, the Kirk of The Final Frontier is closer to the Kirk of TOS than, perhaps in any of the other Star Trek films. He operates within a credo of personal self-reliance, which he pretty much foists upon everyone he’s around. “I don’t want my pain taken away. I need my pain,” Kirk boasts after Bones and Spock both have quasi-religious experiences.

But, The Final Frontier is far less on-the-nose than an episode of The Original Series, and is, in fact, much more sympathetic to people of faith than those TOS episodes in which Kirk beats back false gods. In TOS, if Kirk destroyed or unmasked a false god, he and the crew were simply proven right — self-reliance and Starfleet know-how wins the day again! But in The Final Frontier, it’s more layered. And that’s all connected to the way we think about the character of the rebellious Vulcan — Spock's estranged brother, .

Star Trek V: The Final Frontier

StarTrek.com

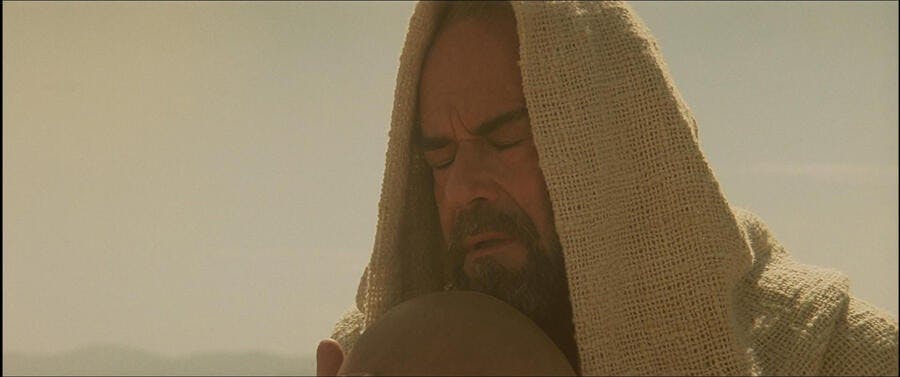

Superficially, Sybok is a delusional con-man; someone who takes up a religious quest and ruins everyone’s lives because of his monolithic vision. But, because Sybok allows people to share their pain, he’s not actually wrong in the way he tries to comfort Spock and Bones about their personal demons. While Sybok does commit crimes, hold people hostage, and steal the Enterprise, I’d offer that Kirk also stole the Enterprise two movies before The Final Frontier in The Search For Spock. Like Sybok, his motivations were personal, and let’s face it, pretty spiritual. From Kirk’s hypocritical point of view, it’s fine to break the law to save Spock’s soul, but it’s not okay for Sybok to break the law to save the souls of, perhaps, everyone.

Kirk and Sybok are equally dogmatic in their beliefs when The Final Frontier begins. Sybok has absolute faith in his quest, and Kirk has absolute faith that God isn’t real. That is, until the last third of the film.

When Sybok mentions the word “God” for the first time, Kirk says, “You are mad.” To which Sybok replies, “Am I? We’ll see.” From this point out, there’s actually an air of humility around Sybok; he ceases to be a creepy con man, and instead, becomes a curious, spiritual person. He’s gotten this far on his quest and now he must wait to see if God will show up.

But God never does.

Star Trek V: The Final Frontier

StarTrek.com

When you’re very young, you know what it is like to want something very badly, but not really be able to picture it. Even if you don’t grow up without a religion, you learn as a child, that having the idea that things will unfold as they should is a universal coping mechanism that many people develop. And so to watch Sybok’s dreams shatter in an instant resonated for me hugely as a child. In that moment, I began to feel sorry for Sybok. He had wanted so badly to meet God, and once he did, it turned out to be an impostor. Not only was Sybok’s quest futile, but his faith was being shattered in front of him. Kirk, Spock, and Bones could easily return to their agnostic status quo, but Sybok had to face the fact that he’d be living a lie.

I’ve never had a brother, and my sister is a well-adjusted, good person. But as an adult I have had close friends who reminded me of Sybok; driven by emotion and passion, believing “with their hearts,” and willing to risk everything on faith. The sympathetic portrait of Sybok helped prepare me for these kinds of emotional extremes in my life.

Star Trek V: The Final Frontier

StarTrek.com

For me, this acceptance of extremes — of not making Sybok a true villain — is the subtle brilliance of this film; the notion that family can be religion, and faith can be friendship. At the beginning of the movie, in the famous campfire scene, Kirk says, “Other people have families, Bones, not us.” Literally, of course, this is not true. In this film alone, we see Bones grapple with the death of his own father, and Spock face his brother, as well as tackle traumatic childhood memories regarding his relationship with Sarek. All of this leads to perhaps the best moment of the entire film.

As Spock reflects about the loss of Sybok, Kirk, Spock, and Bones discuss the nature of family. Eventually Bones throws Kirk’s early comment about not having a family back in his face. And then, Captain Kirk says what I believe to be the most important line of his Star Trek tenure. The line that helped me become tolerant and more understanding of people of faith, whatever their faith might be.

With a smile, Kirk simply says, “I was wrong.”