Published Jan 14, 2022

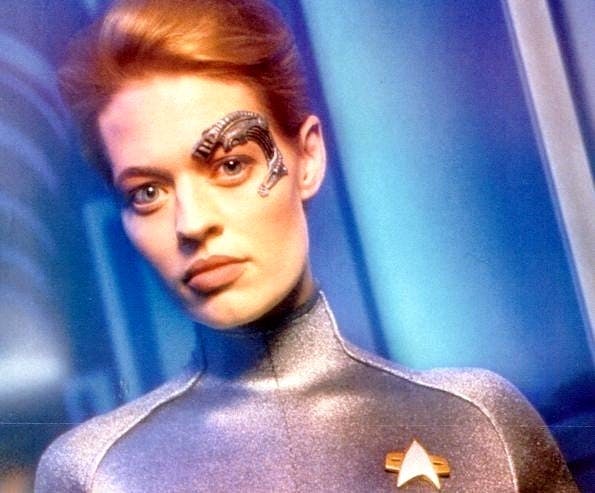

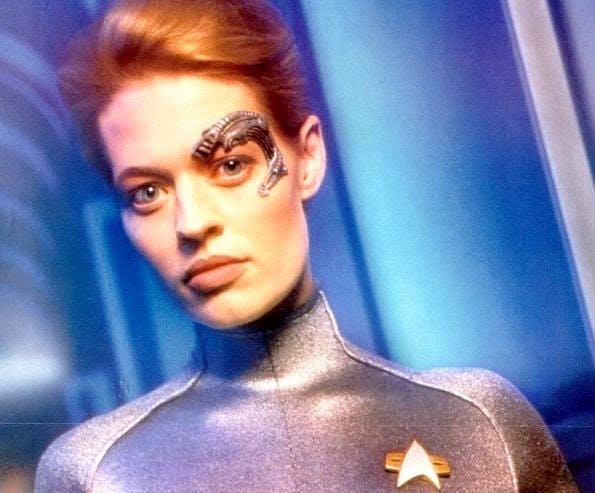

Seven of Nine Was Always Queer

Seven has always represented layered identities, and with Picard she finally gets to show us how far she's come.

StarTrek.com

This article was originally published on June 9, 2020.

For a fleeting moment during the season finale of Star Trek: Picard, we see Seven of Nine, aka Annika Hansen, take Raffi's hand in hers. The two characters look into one another's eyes before the camera moves on to show us how the rest of the crew has fared in the wake of their battle with and for the synthetic lifeforms against the Romulan Tal Shiar.Star Trek fans took that small moment of queer acknowledgement and ran with it—and who can blame us? Getting to see queerness as not subtext, but text on Star Trektook many decades. And, though Star Trek: Discovery beat Picard to overt queer representation, embracing an established and much-beloved character’s queerness not only sends the message that queerness is acceptable, but also that viewers weren’t wrong for clocking Seven as queer for over 20 years. Even Jeri Ryan agrees.

Oh, Seven is canonically bi, don’t you worry.

— Jeri Ryan (@JeriLRyan) May 28, 2020

The truth is that Seven has always been queer. No, I’m not talking about the palpable sexual tension between Seven of Nine and Janeway, nor the substantive number of Seven of Nine/Janeway fanfiction stories on AO3 — though that’s all a part of Seven’s queerness, too. What I’m referencing specifically is Seven’s relationship to her body, gender, attraction, and romance. The way she relates to her body and how her body autonomy has been taken from her by both the Borg and the Federation reads like the experiences of many transgender, nonbinary, and queer folks like me.From the first time Seven of Nine, Tertiary Adjunct of Unimatrix Zero One appears on Voyager, she captures the imaginations of viewers — and Jeri Ryan’s transformation from pale automaton to mega-babe in a shockingly tight bodysuit didn’t historically hurt viewership either. Over the four seasons in which she appears, Seven grapples with her identity as Borg and as human, finding a way to come to terms with the trauma done to her. Romantically, she’s shoved into suggested and real couplings with the Doctor (a hologram), Harry Kim, who turns her down, and Chakotay. She’s a workaholic who ends up raising an ex-Borg child named Icheb and returning to earth with the Voyager crew.

StarTrek.com

When Seven makes her epic first appearance on Picard, she arrives as a lethal space ranger on a revenge mission. She’s hunting down the human that killed Icheb, or rather, left him in such a terrible condition after harvesting his cybernetic implants that it was Seven who pulled the trigger at Icheb’s behest. She is understandably enraged and has no problem manipulating the interests she shares with Picard to get what she wants: A face to face with Icheb’s killer. After he talks her down and convinces her not to kill her, Seven gives Picard a ranger chip so he can call her and tells him something to the effect of, “Oh no, no. I won’t go back and immediately murder her. Unrelatedly, can I borrow these giant phasers?” Of course, she then transports herself back to face the rich ex-Borg implant peddler and kills her.Seven’s other appearances in Picard are equally as violent and powerful. She beats up and kills a bunch of Romulans to save the Artifact, a Borg cube separated from the collective, but still filled with dormant drones and xBs (ex-Borg). She plugs herself into the cube becoming the Borg Queen and destroying the Romulan forces aboard the cube. Then she just hops into the Borg warp conduit to follow and provide cover for Picard’s crew as they reach the synthetic beings’ homeworld.Her feats on both Voyager and Picard are wrapped up in violence, resistance, and philosophical quandaries around body autonomy and that’s part of what makes Seven’s story so queer. She and the Borg, like Data, Soji, and the synthetics, interrogate what it means to be human — and the limits of that humanity. And as history has shown time and again, who gets to be seen as human is determined by those in power; currently, the sitting U.S. president has been attempting to roll back human rights for LGBTQ+ folks and has succeeded in some instances.

StarTrek.com

As a child, Seven was taken to the Delta Quadrant by her parents who were exobiologists studying the Borg. For three years, her parents trailed, observed, and tagged the Borg aboard one cube, all in the name of science. One day, they got too close, their cloaking failed, and all three were assimilated. Seven was around six years old at the time and her family might have been the first humans assimilated into the Borg.Though we never see Seven’s assimilation, we know that unlike adults who are assimilated, she was placed in a maturation chamber where her synaptic pathways were remapped. As part of her five-year dual maturation and assimilation, she had parts of herself stripped away and replaced with cybernetic enhancements. One of her eyes was replaced and her body was filled with technology including in her hands, hips, and brain. It seems that most assimilated people experience extreme pain and fear in the moments when they wait to become Borg and it seems the same was true for Seven. Once a drone out of the maturation chamber, though, we know that Seven, like other Borg, became compliant and connected to the hive mind.The queerness and transness of it all is staggering. Transgender, nonbinary, and queer people have our bodies claimed and labeled when we are young — like the Borg assimilating Seven. Before we can declare who we are for ourselves, we get sorted into blue or pink — never green or black or yellow — and told that we’re only attracted to people who wear the other color; and then those categories are enforced over and over. The surgeries forced on intersex infants are one example of how the gender binary is enforced, and refusing trans teens access to binders, hormone blockers, and other means of harnessing and manifesting our gender identities is another. Adults who jokingly ask children if they have any crushes of only one gender is one example of enforced heteronormativity, while disallowing queer kids to bring their dates to prom would be another.But for 18 years, Seven of Nine lives as a Borg, humming with the connectivity and unity of the hive mind while she enacts the same violence done to her onto others who are assimilated. It’s something she has to grapple with throughout Voyager, but before she gets to that point, she has to face her own de-assimilation. Captain Janeway, acting as the long reach of the Federation, authorizes the Doctor to remove the cybernetic implants that they both know Seven would not elect to have removed. In “The Gift,” Seven begs to be returned to the Borg, begs not to be turned into a human against her will. After stripping her cybernetic implants from her, they even try call her by the name she had as a child, one Seven doesn’t want to be called — until she does. (As someone with two names, two ways of being addressed and perceived in the world, I get it.)In the same way that trans and nonbinary folks are never the same — and in reality, no person nor their relationship to their gender identity is the same — after having a fixed heterocentric gender binary forced onto our bodies and consciousness, so, too, is Seven never the same after she leaves the Borg. The crew of the Voyager can strip her cybernetic implants away, but they can’t remove them all without potentially killing her. They can tell her she’s safe and take her away from the Borg, but they can’t undo the trauma she experienced or the memory of all the violence she did with her own two hands when she was part of the Borg.

StarTrek.com

Who we become after living through the hyper-enforcement of the gender binary, even if we can find ways to live in our true genders and sexualities, is never the same person who could have existed before. We can never be the child who was not assimilated into heteronormativity and neither can Seven. We have to deal with hatred, discrimination, and trauma — including facing the ways we’ve forced others to comply with the gender binary. As she adjusts to her new self and her new identity, Seven is tutored on (aka pressured into) romance and relationships. Both the Doctor and Janeway want her to have normal human connections, to date, maybe one day to marry. And, she tries. She pursues romances, even ones that make literally no sense. In fact, those episodes can be difficult to watch as a queer and trans person, because I can see how uncomfortable Seven is, how little she wants to be in romantic or sexual relationship with those she’s around. Janeway and the rest of the crew just want to give Seven back what she lost. They just want her to be a normal human. But, Seven is still Borg. Just as we are still gender variant and queer.So much of what Seven does on Voyager is to break down the binaries that exist in Janeway’s and others’ minds. Seven is not good or bad. She is not Borg or human. She is both and she is neither. She is Borg, she is human, and she is one of the first of her kind: an xB.

Producing Star Trek: Picard: Hail to the Queen

Seven has always represented layered and conflicting identities. And during Picard’s finale, the way she both helps the humans on Picard’s crew and the xBs aboard the cube highlights how far she's come in learning to accept and reconcile her many identities. Of course, there are lots of ways Seven’s experiences don’t map directly onto queer, trans, and nonbinary experiences, but the parallels are undeniable, whether or not they were intentional.Queerness and transness are not defined by coming out stories or medical procedures, despite the fact that those are the narratives our media focus on. Being queer, trans, and nonbinary is so much more than a label, so much more than a rejection of heteronormativity. It is an acceptance of the multiplicity of being. It is an acceptance of the fact that everything changes. It is an acceptance that we may yet change again. Like many queer and trans folks, Seven’s body is often a site of conflict between her and those that would control, dismantle, or destroy her for her refusal to fit in a binary. But what she does by resisting those labels, by refusing to deny either her Borgness or her humanity, is create space for others: What does the future of the xBs hold? Who knows, but thanks to Seven, they’ll get to find out.

StarTrek.com

When she plugs herself into the Borg cube on Picard, Seven fears she might like being the Borg Queen, she might want to keep control of the drones even after their skirmish with the Romulans. As the Borg Queen she drives the Romulans out of the cube and a member of Picard’s crew looks at her and asks, “Are you going to assimilate me now?”Still the queen, she replies in the voices of the Borg, “Annika is not done yet.” Seven is unplugged from the cube and seems a little shocked by what she said. The moment shows both that Seven doesn’t quite know the limits of herself or her Borgness and that we and the Federation have more to learn about what it means to be Borg and xB. Seven may have been unique for her kind, but she is far from the last—and that’s exactly what it means to be queer, trans, and nonbinary. We follow in the footsteps of our forebears, declaring that we don’t have to assimilate—you have to change.

S.E. Fleenor (they/them) writes fiction and non-fiction centering on queer identities, feminism, pop culture, and literature. They're the managing editor at Bella Media Channel, co-host of Bitches on Comics, and editor of DecodedPride.com. Words appear them.us, Electric Literature, SYFY WIRE, and right here.

Star Trek: Picard streams exclusively on Paramount+ in the United States and is distributed concurrently by ViacomCBS Global Distribution Group on Amazon Prime Video in more than 200 countries and territories. In Canada, it airs on Bell Media’s CTV Sci-Fi Channel and streams on Crave.