Published Nov 26, 2021

Kirk Thatcher Went From a Punk on Bus to a Special Effects Juggernaut

Today, we're catching up with The Voyage Home icon.

StarTrek.com

This article was originally published on February 4, 2021.

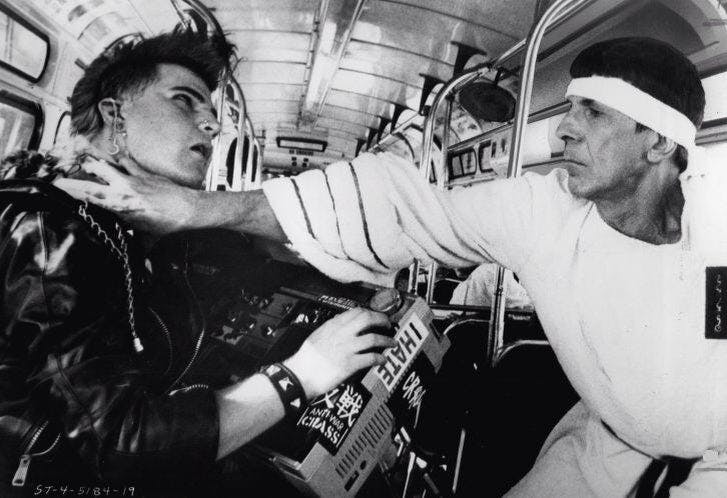

How long does it take to become an icon in the Star Trek universe? For Kirk Thatcher, just under two minutes. In 1986, the associate producer of Star Trek: The Voyage Home made a rare on-screen appearance as the orange-mohawked Punk on Bus, in which Spock gave him a Vulcan nerve pinch after he refused to turn down his boombox. While this memorable scene made Thatcher a bold-faced name among Trek fans, it’s just one facet of a multi-decade career in front of and behind the camera on such geek-friendly properties as Star Wars, Gremlins, Robocop, and The Muppets. Recently, StarTrek.com caught up with Thatcher to find out about his memorable cameo and learn more about what he’s doing now.

Getty Images

StarTrek.com: Were you a Star Trek fan as a kid?

Kirk Thatcher: I was! I liked it as a show that looked at hardcore science-fiction tropes, mirroring our society and playing with the what-if. To me, science fiction — and fantasy, to some degree — answer “what if” with different trajectories. For Christmas I got an Encyclopedia Britannica, and the next year I got a wildlife encyclopedia… My mom, to round out my interests a bit, said to me, “What if you try science fiction? [Those are] books based on the ‘what if’ but following a more science trajectory.” So then I got hooked and all I read was science fiction and the science encyclopedia. And Star Trek just hit me between the eyes, because it was obviously entertaining — it had pretty women in skimpy outfits and cool ideas of what aliens looked like — but more importantly to me, the concepts of it (were appealing). I was primed to love Star Trek from the get-go, and I did!

What was your career like before Star Trek?

KT: I grew up in the San Fernando Valley, which was essentially the bedroom community of Hollywood. Everyone who was employed as a worker bee most likely lived in the Valley. I knew it was a job. It wasn’t something done halfway around the world, where I saw the resulting product but I didn’t know how it happened.

I’d already been interested in special effects and sci-fi and fantasy before Star Wars came out, but when [A New Hope] came out, I said “I wanna work on those movies.” Not only were they doing it with a sense of fun, but the design, the aesthetic of it, was just amazing, from the creatures to the spaceships. I’d already decided I wanted to work for Walt Disney Imagineering or work in the movie business. I happened to be fortunate enough to work down the street from (Industrial Light & Magic) where it was originally based in Van Nuys.

My mom came home from church one day and said a lady from church had a son who worked on Star Wars. It was Joe Johnston, who designed all the spaceships and storyboarded the parts of the movie with the spaceships. I met Joe, he gave me a tour, we stayed friends through my high school years, and I told him “I want to work for you guys.” I was super excited because I could ride my bike to ILM, but I was only 15. I kept in touch with him. ILM moved to San Francisco, which was a bummer as we would say, because I couldn’t get a summer job there.

After a year at UCLA, I wrote to Joe, said “I’d like to work there — I’ll sweep the floors there,” and he put me on a list of people to interview for the creature shop. I worked on Return of the Jedi for a year and a half, making creatures — molding, casting, painting, puppeteering in a couple bits.

[After that] I worked on Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan, helping cast and paint the Ceti Eels, and on The Search for Spock I worked on set for about a week, either puppeteering the bacteria worms that came out of Spock’s space coffin or the lizard dog, the Klingon pet that sat next to Christopher Lloyd’s chair in the Bird of Prey. There was a hollow space under Christopher Lloyd’s chair, and I was curled up under there with a monitor so I could see what I was doing. I was just keeping him alive and making him look around — I didn’t want him to steal the scene.

After that, I went back to UCLA to learn computer animation, because I figured that was going to take over the effects business. While I was there, Star Trek set up a production office for The Voyage Home. They [contacted me and] said “Leonard Nimoy is looking for an assistant who knows special effects and the film business.” What [Nimoy] said when I interviewed with him was that he was frustrated because he wanted someone on his team — literally his guy — to consult with him about the effects. We hit it off. I got the job as his assistant, and when we started filming he said, “I wanted to make you associate director, but the Director’s Guild won’t allow that. ‘Director’s Assistant’ sounds like you [run errands], and you’re very much a creative part of this. Would you mind if we called you Associate Producer?”

I said “are you kidding me? You could call me Chief Chucklehead and I’d be happy!” I had a background in effects and design and production design and all the things he wanted someone on his team to know, but he didn’t want to deal with the minutiae. I think he also felt overwhelmed, and he said “I want you to take care of all of that. If someone asks what color a Klingon’s beard should be, you tell them.”

StarTrek.com

How did you get the role of Punk on Bus? Were you a punk fan?

KT: As a high school student I loved punk music a lot. What I liked about punk was not only the catharsis of jumping around and screaming and going “I’m angry” — I also liked the joyful anarchy about it, particularly the sense of humor.

The script came in with this punk scene. I felt just close enough to Leonard to say “hey, I’d like to play the punk,” ‘cause I was, what, 23 — I was still in that age range. I just said to him, “I’d like to play the punk,” and he said [impersonating Nimoy] “Reeeeeeally,” and I said “yeah! I think I’d do a good job. I was in a punk band. I know the music. I’ll get a mohawk.”

He said, “All right, let me think about it.” I hadn’t badgered him about it because I knew that would not go well. I worked with the guy, I had to work with the guy for another year, so I wasn’t going to become a pain in the neck. About a week later, we had our chat to wind down the day, and I was literally walking out the door, and he said “And one more thing...You can do it.”

I said “wait, are you serious?” I knew what he meant; I probably wasn’t that great at covering. He said, “Yeah, yeah, and don’t disappoint me.” And I said “Oh! No! Don’t worry! It’s gonna be great!”

I went down to Melrose [Avenue], the big punk fashion district, and bought the earrings and the dog collar and the iron cross earring. And the cheap-ass leather jacket. The makeup I just did with the makeup gals. I had my friend who did my hair when I was a demi-punk bleach my hair twice to get it almost white so the orange would really show up, and then she shaved the sides the week before we shot, so I had an orange mohawk for about three months.

We shot it on the day on the actual Golden Gate Bridge. I think we went up and down about five to six hours of driving just to get the scene — not just me, but also him and Bill [Shatner] talking. We had to wait because we were only driving north to Sausalito, so we could only shoot that two-and-a-half–minute drive and then turn around, come back, and start again. My take of the thing, I think we did that in two runs. Mine might have been the last scene [that day].

All the camera equipment was on the back of the bus. We had a joke about “aliens at the back of the bus,” but that was the easiest place to pull all the seats because we had to pull the dolly and the camera and the sticks in there. There was no music on the boom box and I was just miming it and keeping a rhythm of “duh-nuh-nuh-nuh-nuh-nuh-nuh”—some fast beat, knowing what punk was like.

You also wrote the song that’s playing on your boom box.

KT: We were in post-production and the music department had said, “oh, we’ve got Duran Duran or Spandau Ballet for the music,” and I said “Oh Leonard, that’s not punk! You want the Dead Kennedys or the Sex Pistols.” The music guy said, “They’re going to want too much money for one song, and it’s not an important song.” So I looked at Leonard and said “Dude, I’ll write the song! I know what punk is!”

He said, “okay, show me what you’ve got,” and I wrote the lyrics out in 15-20 minutes. They came to me really fast. I didn’t know how to play an instrument at that point, so I said to [sound designer] Mark Mangini, “Do you want to write the music for this song?” He wrote the guitar chords and played them. Three of the sound guys were the musicians and I was the vocalist. We recorded it in the hallway, so it sounded horrible.

Leonard came in to [the editing bay] to listen to the whale sounds, so we played it for him and he was frowning and looking slightly disgusted. When it was over he said, “Oh, it’s terrible, it’s awful.” I’m trying to figure out how to save it, and he says “So it’s perfect!” That was his sense of humor.

StarTrek.com

Where did the band name Edge of Etiquette come from?

KT: It was a joke, because my personality is kind of garrulous and silly. I would say things in these production meetings to the head of the studio, just making a joke and keeping it light. [After one of the meetings] someone said, “Man, you just walked the edge of etiquette.” So I put that in the back of my head, so that when someone asked me “what do you want to call this ersatz band you threw together for the song?” I said, “Oh, the Edge of Etiquette!”

More recently, you narrated an episode of Star Trek: Short Treks.

KT: I played the Punk on the Street in Spider-Man: Far from Home. I’m in that for a quick bit with the boombox. That was all Kevin Feige. He was a big Star Trek fan. Michael Giacchino, who scored JJ’s Star Trek movies, did the score for my Muppets Wizard of Oz movie and we’ve been friends ever since. He’s a big Star Trek guy with a sense of humor. He was talking to me about his Star Trek short and was showing me the [story] boards, and I was like “Wow, this is great! It’s a love letter to the fans of The Original Series.” And he said “Hey, would you like to do the narration.” We played around and I went with a British naturalist documentary voice. I recorded a scratch track, and as the animation got finessed, I recorded it two or three times as a scratch track and then went in for the final recordings. It was one of the last things they were doing. The Trek world is a small world!

Kirk Thatcher is currently working on two projects that should be released before the end of the year.

Chelsea Spear (she/her) is a frequent contributor to The Arts Fuse and Crooked Marquee. She lives in Boston. You can find her on Twitter at @travelswbrindle.