Published Sep 11, 2023

I Was a Child of Mars

For one fan, this Short Trek evoked one of the most memorable days of Millennial childhood.

StarTrek.com

I didn’t expect to cry as hard as I did.

Oh sure, I’ve cried at StarTrek before; episodes with Holocaust allegories like “Duet” and “Ties of Blood and Water” got me, as did ’s first season finale when Michael Burnham at last earns her redemption; and of course at “City on the Edge of Forever” from . Last week, however, when I sat down to enjoy the newest Star Trek: Short Treks, “,” I was watching with an eye for clues as to the plot points for the premiere of . What I found instead was something much more significant.

"Children of Mars"

StarTrek.com

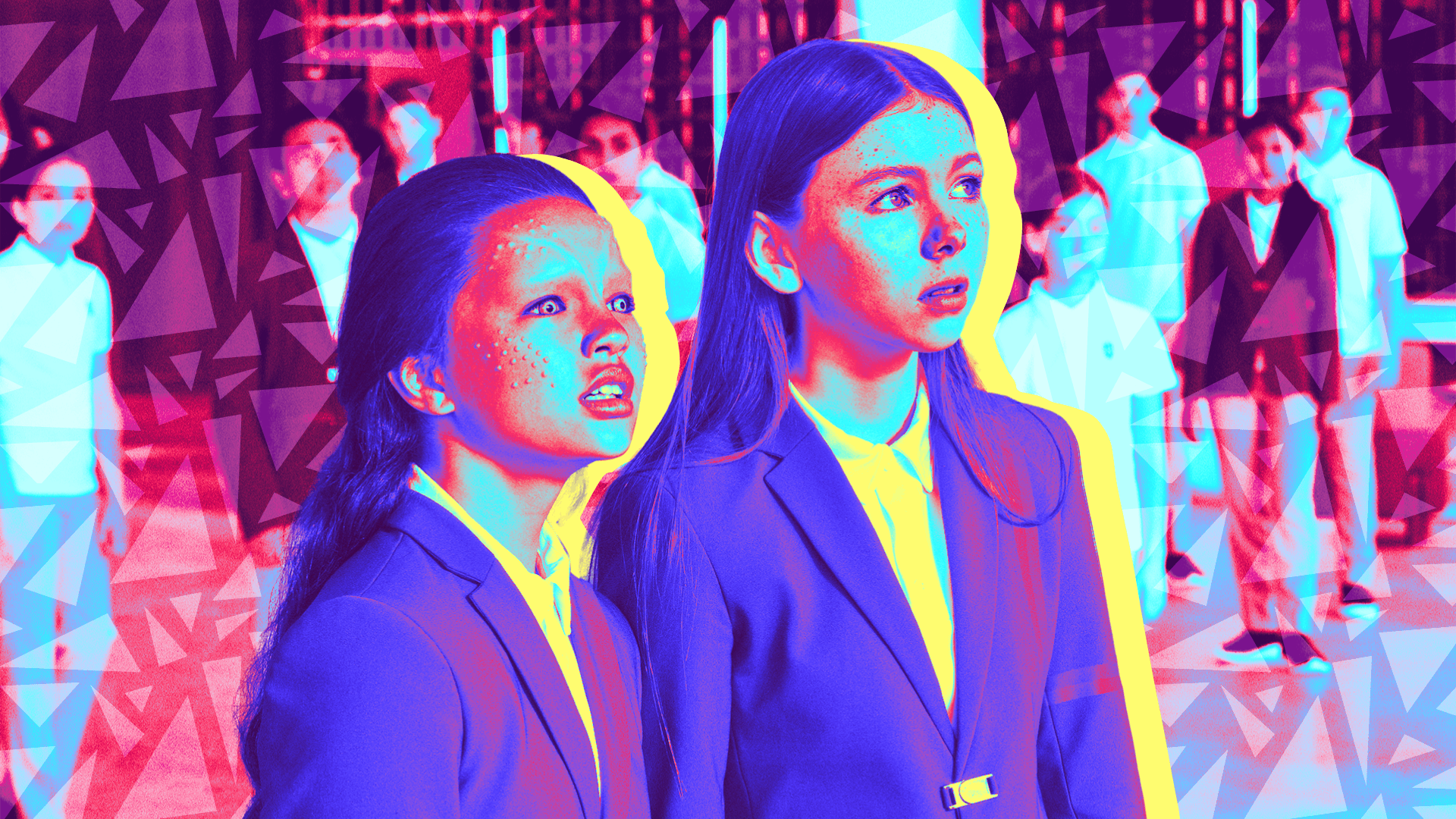

“Children of Mars” opens by introducing us to Kima and Lil, two middle school girls on Earth, who each have a parent who works on Mars at the Utopia Planitia complex, where Federation starships are built. For the girls, their day begins as normal as a school day can; they start their morning space-Facetiming with their parents. At the bus stop, Lil knocks Kima’s backpack off, making her miss the bus, and in retaliation, Kima trips Lil in the library to get her back. The two girls devolve into full on fisticuffs in the hallway, as the other students egg them on. They end up, of course, outside the principal’s office to be disciplined, when the unexpected and tragic happens.

There’s been an attack. The principal receives an emergency alert. A teacher approaches him, tears in her eyes. The emergency broadcast is on all the computers. Within seconds, it’s on the big screens, wiping away the inspirational messages of “Achieve! Grow!” with scenes of horror — news footage of an aerial assault on the Mars shipbuilding complex. There are screams of terror, scenes of workers fleeing down smoke-filled staircases, video of ships laying waste to Mars. Within seconds, the entire school is drawn from their classrooms to watch the horror. Kima and Lil, no longer enemies, no longer even children, reach out for each other’s hands, knowing that they each have a parent at the Mars complex. In their eyes, I could see childhood was over. I knew every ounce of what they felt — shock, confusion, horror, and most of all, fear. Raw, unfiltered, human fear. As a single tear runs down Kima’s cheek, thinking about her mom, I found I too was crying. I felt this story so profoundly, because their story, a regular school-day upended, everything known suddenly becoming the unknown, the abrupt jolt into adulthood was my story.

"Children of Mars"

StarTrek.com

I was in sixth grade at another regular school on a Tuesday in September. I lived on the Connecticut shoreline in a town where many parents commuted into New York City every day. A place my dad often went for work, not every day, but sometimes. I was in second period — science class — when an aide entered the classroom, stopping my teacher mid-sentence to hand her a piece of paper. What my teacher read, in a stiff, dry, disoriented voice, was that a plane had crashed into the World Trade Center. I remembered feeling confused, I leaned over to my best friend and asked him why would we have class interrupted with an announcement about an accident. That was when my teacher said it, slowly, and she looked around at all of us to tell us, this wasn’t an accident. This was an attack.

When class dismissed, kids flooded into the hallways, and the announcements began. First, it was a crackle of the loudspeaker as a student’s name was called down to the main office. A girl in my English class. Then, minutes later, another name was called over the PA.

Then another.

Then another.

"Children of Mars"

StarTrek.com

One by one, kids from all over my school were being called down to the office. The girl from English class didn’t come back. Rumors abundant, they said thousands of people were dead. Someone in the hallway said darkly that the kids being called down to the office were probably being told their parents had been killed or injured in the attack. In reality, it was that parents wanted their kids home, together with them during this tragedy. My stomach felt tight, like I’d been vomiting for hours, the first use of a muscle I’d never felt before, but I knew what I was feeling — fear.

…and then, it happened. I was in math class, and the loudspeaker crackled, and the principal spoke my name. “Nick Mancuso, report to the main office.”

I felt my fingers grow cold. I looked to my math teacher, who nodded, and I rose from my seat slowly. Time felt as though it was taffy, stretched, rubbery, and slow. My dad sometimes worked in New York. My dad had been to the World Trade Center before on business. Here I was, being called down to the office. I heard the echo of that student’s speculation in my head. I was going to be told my dad was gone.

I remembered walking down the brutalist hallway of the middle school, the painted cinder block walls, the way the musty carpet smelled. I remember the clothes I was wearing, the way my sneakers felt on the ramp down toward the main office. I was going to learn my dad had died. I felt shaky, and my cheeks felt tight. As I approached the office, I could see my Mom standing there, her purse on her shoulder. I could feel my breath in my throat as I reached for the polished steel of the door handle. I twisted it, and pulled it open.

"Children of Mars"

StarTrek.com

My mom looked at me. She wasn’t smiling, but she didn’t look like she’d been crying either. She had a grim look on her face, her mouth a flat line.

“Where’s dad?” I stammered. She looked confused.

“What? Dad’s at home, I’m taking you to the doctor to get shots. I didn’t want you to worry about it all morning.” In the doctor’s office waiting room, I saw the footage for the first time. It was so much worse than I’d imagined; people jumping from windows, the second plane impact. When we got home and dad met us, I fell apart, climbing up into his lap on the couch, 11 years old, and perhaps too big to sit in my dad’s lap. He began to cry too.

As tragedy unfolded for Kima and Lil, all their petty quibbles, their fighting, their impending discipline from the principal all vanished. Their innocence, their childhood problems were gone. As tears filled their eyes, mine did too, because I knew who these girls were. They were me. In this effective eight minutes, I saw myself at 11 years old, frightened for not only for my parents, but my friends’ parents, for the world I had always known. Their eyes were the eyes of children hurled into adulthood, the panicked faces of the adults, our teachers and principals and parents, the faces we were supposed to look to who knew everything, who taught us everything, just as terrified as we were.

Episode Preview | Star Trek: Short Treks - Children of Mars

The story ends there, of course. We don’t know what happened to Lil and Kima’s parents. We don’t know if, like me, they had their teary-eyed English teacher threw aside her lesson plans that afternoon to have a discussion with us about Islam — to explain that in the coming days, there would be a lot of hatred targeted at Muslim people, and we needed to stand up against it. This handful of violent men had nothing to do with the beautiful, ancient faith millions around the world celebrate every day.

We don’t know if Kima and Lil made it home to see their parents that night. I don’t know if they got to climb into their father’s lap like I did, his big hands squeezing my bony 11-year-old shoulders. I hope, for their sake, that their story ended like mine did because, in real life, 2,977 families on that morning, weren’t afforded the ending I was.

Star Trek has always told us stories of who we can be, and more importantly, who we should be. But when I witnessed “Children of Mars,” and I saw myself, right there, 11 years old, it was the first time Star Trek showed me something I’d never experienced before in a show about galaxies and science, aliens and starships. In “Children of Mars,” Star Trek didn’t show me who we should try to be, but for the first time, it showed me who we are, and how we live today.