Published Dec 4, 2020

How to Meet a God, According to Star Trek

Star Trek provides us a useful guide on what to do in a variety of situations when encountering divine beings and their adherents

StarTrek.com

The greatest moment Captain James T. Kirk’s career happens in Star Trek V. No, really, come back! Sit back down please, I’m serious.

StarTrek.com

Face to face with the awesome and almighty power of God, Kirk stops everything — interrupting the real or figurative rapture of those around him — and awkwardly asks why God needs his starship.

In the face of potentially the greatest answer to all the big questions, to the question, Kirk instead continues asking questions. In essence, he chooses to continue to explore, seek out, and boldly go rather than accept at face value and go home.

Star Trek’s mission statement has often seemed at odds with religion. If faith is about trust and belief without seeing, the mission of Starfleet is that not only are we going to go see, we are going to scan, catalogue, and decipher whatever it is we see when we get there.

There was no chaplain aboard the Enterprise and, while there is occasionally a room for a wedding or the like, the only Chapel to be found was the long-suffering nurse. Yet despite its seeming agnosticism, Star Trek in its many forms has not shied away from tackling issues of humanity’s relationship with God and faith. So perhaps, if it can provide a roadmap for a better future of technology, race relations, and politics, it can teach us something about what to do with a God as well?

What to do when someone claims to be a god:

StarTrek.com

James T. Kirk bookends his career arguing against men claiming to be gods. Long before he passed on his “Noah’s Ark” moment and denied the false God of Star Trek V a trip aboard the Enterprise, Kirk matched wits and karate chops with his best friend turned omnipotent being Gary Mitchell in the second pilot for The Original Series, “Where No Man Has Gone Before.”

Mitchell’s claim is that he is a god by virtue of gaining godlike power (because of space rays, it’s a long story). To Kirk’s credit if any of your friends suddenly turned around and told you to worship them you’d probably give them a karate chop or two yourself.

It isn’t that Mitchell is bad. Far from it, the first thing he does with his power is save the Enterprise from blowing up its impulse deck. But the real danger presented by godlike beings is argued by Spock, who concludes that they have to kill Mitchell immediately, saying that soon, “We’ll be not only useless to him but actually an annoyance.” Spock’s argument prevails and they dispose of Mitchell. Though one wonders if upon encountering their next of many godlike aliens coexisting just fine with mortal beings, perhaps Spock felt a bit sheepish about it?

A century later, Worf has several crises of faith, encountering both the Klingon Satanic figure Fek'lhr (actually a conwoman in disguise) and the messianic Kahless (in clone form). Worf would later present the Klingons extremely practical solution to theological issues: “Our gods are dead. Ancient Klingon warriors slew them a millennia ago. They were... more trouble than they were worth."A sentiment Spock would no doubt approve of.

What to do when someone is indistinguishable from a god:

StarTrek.com

From the Organians of The Original Series’ "Errand of Mercy", to Voyager’s "Caretaker", Star Trek has no end of seemingly omnipotent beings, who could, if they wished, make a good case for godhood. Rarely upon encountering these beings do Starfleet crews fall on their faces and choose worship, so some level of skepticism even in the case of miraculous power should be observed.

However, at least one of these beings actually claimed not just to be “a” god, but “the” God, in the Abrahamic sense.

When Captain Jean-Luc Picard dies on the operating table in TNG’s “Tapestry,” Q tells the captain that not only is he capital-G God, he’s also in charge of the afterlife. Q claims to be omnipotent (and this is never disputed) but is cosmic power enough for legitimate godhood? To answer this, we must ask what we think a god is.

Merriam-Webster helpfully gives a god the attributes of power, wisdom, and goodness, also adding that they are one “who is worshipped” and seen, in some cases, as creator of the universe.

Certainly goodness and creation are optional elements. These are largely Abrahamic concepts and don’t always apply in comparable theologies. Zeus is not the creator of the universe, he just rules it, and Inanna (the Sumerian goddess of love and war) is sometimes quite frankly a jerk. The necessity of having worshippers as a criteria is also interesting, as it suggests that to be a god someone has to recognize you as one.

So is Q a god? Well, yes, though it depends on who you ask.

StarTrek.com

It is unclear if Q really believes himself to be a god, though it seems unlikely. But nevertheless he was considered a god, as confirmed by Vash, on the Gamma-Quadrant planet of Brax, where Q was referred to as the God of Lies. His relationship with humans could also qualify him as some form of trickster-god in the tradition of Loki.

This does not stop Picard (or indeed any human whom Q encounters) from denying his divinity outright. If Q is a god, perhaps Picard is something of a Job-like figure, being constantly tormented to test his worthiness.

It’s possible that Picard does not recognize Q’s godhood simply because that just isn’t how people think in the 24th Century. In fact, Picard ironically invokes the Watchmaker Analogy (“if the universe is so well designed there must be a divine planner”) to argue against Q, saying “I refuse to believe that the afterlife is run by you. The universe is not so badly designed.”

What to do when they actually are a god:

StarTrek.com

“What in the name of-” says Dr. McCoy as the Hellenic god Apollo stretches forth his hand and grabs the Enterprise out of the sky. McCoy never does get so far as the last word in the phrase, and neither does the episode, despite the fact that Apollo is indeed the god he claims to be.

Kirk’s Enterprise crew encountered several mythological figures of Earthly origin over their five year mission, including the Mayan snake-god Kukulkan and even Lucifer himself, both in animated form.

What’s fascinating about Kirk’s reaction to meeting a Greek god is his cognitive dissonance. He is the first to realize that this person could indeed be the real Apollo, and the first to apply the “ancient aliens” theory to explain why this is, but he also asserts that Apollo is not a god.

He responds, saying, “mankind has no need of gods,” not because they have outgrown religion, but because they “find the one quite adequate.” So it’s possible Kirk is a monotheist, believing only in one omnipotent creator-God as opposed to an atheist or even a henothist who could believe in the possibility of multiple gods while still thinking their particular one is best.

Kirk is, after all, another word for church.

Another interesting facet of Apollo’s appearance is the crew’s rejection of his offer of paradise in exchange for worship. Sure, if someone came along asking you to kneel to them you might scoff, but life in paradise seems like it would be a harder pass.

Still, whenever a Star Trek crew is offered life in a utopia (outside of the Federation), they refuse, argue, and frequently punch, saying in essence that struggle and imperfection are the way life really is. It’s a tradition stretching back all the way to the first pilot, “The Cage,” and it adds an interesting wrinkle in Star Trek’s claims to being utopian fiction.

What to do when they are someone else’s god:

StarTrek.com

Gene Roddenberry’s secular humanism in the face of divinity ends where Deep Space Nine begins in several interesting ways. Where other series merely dabbled with meeting a god or two, much of the plot on the titular space station revolves around the alien pantheon of the Prophets of Bajor.

Far from the confrontational approach of a Kirk or Picard, DS9 allows us to watch as Benjamin Sisko finds faith in the Prophets and their plan for his life — to the point where he is willing to abandon Starfleet, give himself over completely and, like Abraham, even sacrifice his son to their will.

Confusingly, the word “prophet” means ‘one who speaks with or for a god.’ They are not the god themselves. There doesn’t appear to be anyone above The Prophets in the Bajoran religion, so perhaps this is a mistake of the universal translator.

The rest of the Starfleet officers on DS9 behave in a very Starfleet-ish way, not really accepting the divinity of the Prophets, per se, but respecting the Bajoran belief system and culture. Though they are also not above pointing out harmful or irrational aspects of this, as when Major Kira’s faith led her and others to accept an archaic “D’jarra” or caste system in which she was required by her gods to sculpt a rather unfortunate play-doh duck.

They also generally refer to the Prophets almost exclusively as “wormhole aliens” which, while certainly accurate, can’t help but come across as a bit rude!

What to do when they claim that, actually, you are a god:

StarTrek.com

“If someone asks you if you’re a god, you say yes,” the Ghostbusters’ Winston Zeddemore wisely said.

By the 24th Century it is implied Starfleet has access to tests and ratings for telepathic ability and exotic energies, which might have cut through some of the confusion surrounding claims of divinity if a tricorder had incorporated the function of a Ghostbuster PKE meter. But, Jean-Luc Picard would disagree regardless.

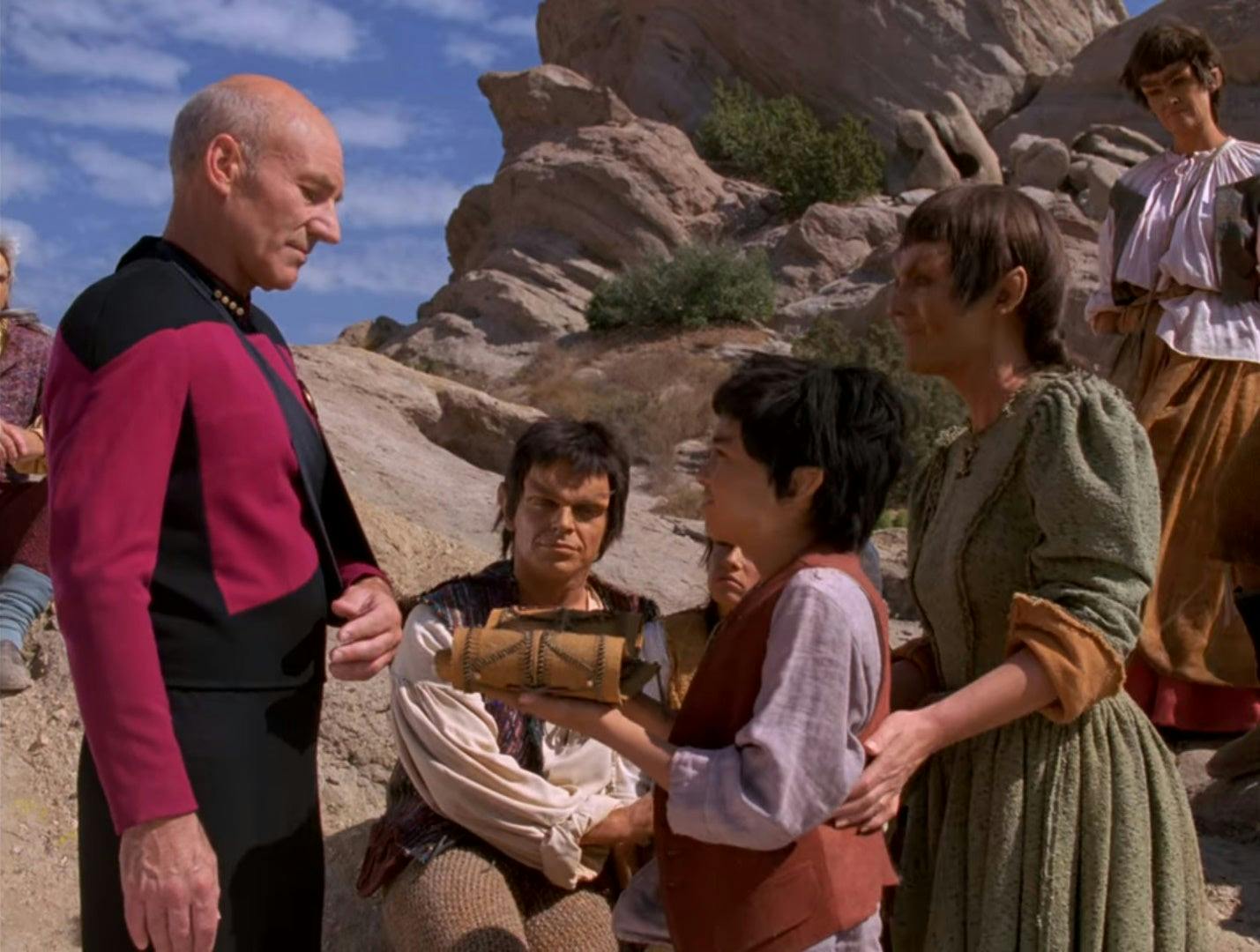

When mistaken for a god by the bronze-age people of Mintaka III, Picard must decide whether he should take the easy road — lean into this god stuff, and tell the Mintakans to give back his people — or, alternatively, violate the prime directive and explain to them the whole advanced civilization from space thing.

Picard, who appears substantially more agnostic than Kirk, is even encouraged to pose as a god and dictate commandments. He refuses this suggestion (posed by an anthropologist studying the Mintakans) in perhaps Star Trek’s most fiery condemnation of religion:

“Dr. Barron, your report describes how rational these people are. Millennia ago, they abandoned their belief in the supernatural. Now you are asking me to sabotage that achievement, to send them back into the dark ages of superstition and ignorance and fear? No!"

StarTrek.com

Still, for all his righteous fury Captain Picard is not above celebrating a classic Christmas morning which just goes to show that sometimes the best way to encounter different people’s beliefs is to just relax, enjoy the decorations, and get over yourself.

John de Lancie on Creating a Star Trek Icon

Andrew Hawthorn (He/Him) is a journalist and comic book writer living and working in St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador. His credits include writing for CBC News and Tales of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. He thinks Star Trek VI is better than II, but only just. You can follow him @hawthornandrewj on twitter and instagram.