Published Mar 22, 2021

How Captain Kirk Helped Me Define Masculinity

...and find my name.

StarTrek.com

My name is James – yes, like James Tiberius Kirk – but it wasn’t always.

Getting to James a tad unconventional. Though no one calls me this now, I started going by Jim when I was 15 or 16, once again, inspired by my favorite Starfleet captain.

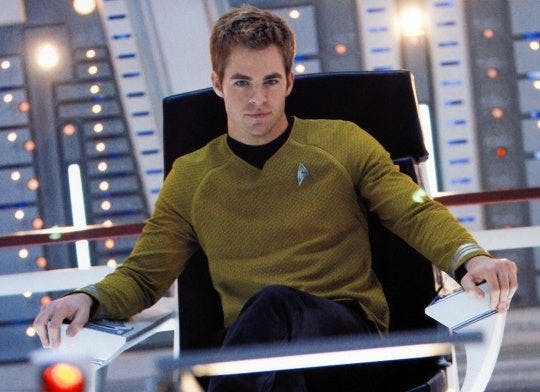

Unlike many Star Trek fans I didn’t actually grow up with the series. I was a nerdy kid, raised in a strictly Star Wars household, and like many members of Gen Z, I was introduced to Star Trek by the 2009 J.J. Abrams movie. I don’t remember the first time I watched it (I was 11) and it didn’t leave much of an impact on me at the time. Coincidentally, this was also around the time I first started realizing that I had feelings for girls, as a girl on the verge of adolescence myself.

I revisited Star Trek as an out, queer teenager in 2013 when Into Darkness was released. To my surprise I saw a lot of myself in Star Trek (2009) this time around, namely in the character of James Tiberius Kirk – and I don’t just mean his penchant for ‘90s alternative rock (but yes, also that).

StarTrek.com

Like Kirk in the first movie, I was a kid with a lot of pent-up emotions that I didn’t quite know how to process, using a leather jacket as protective armor instead. My dad didn’t die heroically in a starship crash and I didn’t throw fists at the slightest provocation, but coming of age as an openly queer person of color in a predominantly white school district came with its own set of challenges and sense of alienation. Kirk was clearly someone in pain, someone who needed help, someone who desperately needed someone to believe in him. I was too.

When that believer came along in the form of Christopher Pike, I could picture myself within that dynamic as well. The scene right after Kirk gets the crap kicked out of him by some cadets after he tries (and fails) to flirt with Uhura hit me surprisingly hard. Kirk and Pike are sitting at a table in a bar as it’s closing and the latter remarks upon the former’s aptitude tests, which are “off-the-charts,” despite his repeated delinquencies. Pike asks, “Do you feel like you were meant for something better? Something special?” Kirk’s non-answer as he avoids eye contact with Pike speaks volumes.

For me, home was the suburbs of Los Angeles, not the cornfields of futuristic Iowa, but I too felt trapped. I too yearned for something greater. And I too had that exact confrontation with teachers over and over again. I was a bright kid, they said. I had so much potential, but I could be doing so much better if I just applied myself. Applying myself, though, proved difficult with the combined weight of various social ills, burgeoning gender dysphoria, and a case of undiagnosed ADHD bearing down on me (the latter which I suspect Kirk to have as well, but that’s a subject for a different article).

I found my solace in Star Trek. Urged by a fellow nerdy, queer, person of color, I expanded beyond the reboot movies and started watching The Original Series in high school. I fell in love with the wonderfully imaginative storytelling, the costuming and flawless makeup (Spock’s eye shadow stays on point), the creatures from the Gorn to the Tribbles, and even the camera shakes. Though it was different from the movies that initially drew me in, TOS provided me with the same escapism. My own world might have been oppressively dark, but with the click of a button I could be transported to the technicolor world of 1960s Trek and be reminded of the goodness and light at the core of all sentient beings — human or otherwise.

StarTrek.com

I saw myself in this original iteration of Jim Kirk too, or at least I wanted to. Shatner’s Kirk was the epitome of masculinity. He’s suave, cool, and collected – except for the occasional instances where his shirt “inconveniently” rips in battle. Beyond that, his masculinity is based on deep respect and love for his crew, for the diverse species he encounters in his travels, for the women with whom he liaisons. While he has a strange reputation in pop culture as a womanizer, there’s no real evidence to support that in TOS. That was the kind of masculinity I aspired to cultivate, one that was about care and not callousness. Also, both Shatner’s Kirk and Pine’s Kirk have killer hairstyles. Who wouldn’t want that?

In the second episode of TOS, “Charlie X,” the Enterprise picks up the titular character, a 17-year-old boy who grew up alone in the remains of a shipwreck and is accordingly unfamiliar with social mores. Kirk literally has to teach him how to be a man, which he does in an intervention spurred by Charlie’s harassment of Yeoman Rand. He urges him to be slow and gentle and not put pressure on women, and teaches him that attraction is “not a one-way street.”

When Charlie resists his teaching, Kirk tells him, “Charlie, there are a million things in this universe you can have and there are a million things you can't have. It's no fun facing that, but that's the way things are.” Charlie responds, “Then what am I going to do?” and Kirk says, “Hang on tight and survive. Everybody does.” The last two sentences in particular were exactly what I needed to hear as a 17-year-old myself. The simple act of surviving was (and still is) a monumental struggle at times; to hear that even someone like Kirk went through that struggle meant a lot. It spoke to me so much that I made those two sentences my senior quote in high school, and a subtle shout-out to my namesake as well. I might have been in the closet, my birth name printed below my yearbook picture, but the name I chose was there too, however indirectly.

StarTrek.com

It’s more accurate to say I had one foot in the closet, one foot out. Everyone knew I was queer, but going by “Jim” was a secret, confined only to the Internet and my girlfriend at first, then to my close friends, then to my high school’s LGBT club. Along the way, I decided that I liked the more formal “James” better, and when I got to college that’s how I started introducing myself.

The name has stuck with me through a myriad of pronouns, gender identities, and sexualities. Right now, I use they/them pronouns and identify as a lesbian (and have for a while); calling myself “James” feels more right than ever. My identity may not make sense to a large portion of the world, but Star Trek also taught me the old standby of Vulcan philosophy: Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations. To me, that crucial tenet means making space for all the potentialities of who I am and will become. It means I can identify, to some degree, with womanhood but have a traditionally male name – just like Discovery protagonist Michael Burnham. It means I can be masculine without being a man. If the Vulcans can celebrate the vast spectrum of variations in life across the universe, I can certainly celebrate that in myself and others.

Now, a decade since Star Trek (2009) was released and five years since I adopted my name, I’m still in the process of coming out. It’s happening, though, slowly and surely. And hopefully this December when I graduate college early (like Kirk did at Starfleet Academy), I’ll receive a diploma with my proper name on it. I can only hope to live up, in some small way, to my namesake’s legacy.

Captain Kirk vs. Gorn

James Factora (they/them) is a writer and musician in New York. You can find them on Twitter @james_factora.