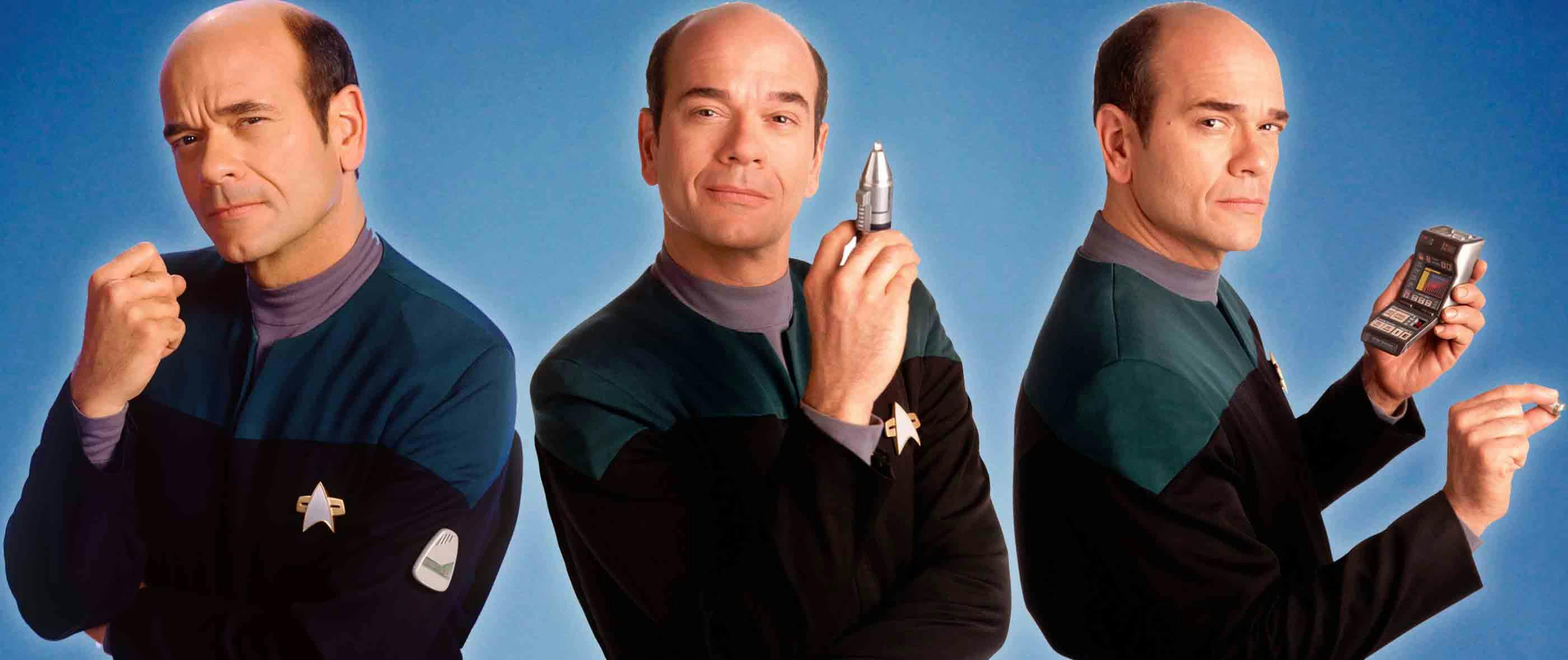

Star Trek has always emphasized character development. During the multi-year course of a Trek series, we witness the relational, intellectual and ethical growth of individuals and these changes make the stories told in each show compelling. One of the most interesting characters to watch was the holographic doctor in Star Trek: Voyager, magnificently portrayed by Robert Picardo. The Doctor began as a protocol emergency hologram and over the course of years became an independent person and important member of the crew. He also grew in his vocation as a doctor and his understanding of what medicine was intended to accomplish. This growth is seen most poignantly in the episode titled “Critical Care.”

In this episode, the Doctor is kidnapped by an unscrupulous trader named Gar, who negotiates a price with an alien administrator named Chellick of the Dinaali people. This occurs just as a group of trauma victims from an explosion arrive at the hospital, which is in an unsanitary, deplorable condition. The Doctor leaps into action attending to the injured and Chellick notes that this quick action is contrary to the Doctor’s initial protests regarding his situation. The Doctor responds succinctly, “Fortunately for these patients I am programmed with the Hippocratic Oath. It requires me to treat anyone who is ill.”

Hippocrates was the ancient Greek philosopher, who we know from Plato was a contemporary of Socrates. He was well known as a practitioner and teacher of medicine and is the person for whom the modern Hippocratic Oath is named. In his work, On Medicine, Hippocrates seeks to define what medicine is. He writes, “Let us inquire then regarding what is admitted to be medicine; namely, that which was invented for the sake of the sick.” Like Plato after him, Hippocrates understood medicine to be a craft and the skills of the craftsperson are aimed toward a particular object. Just as the carpenter’s craft is aimed at construction and the teacher’s craft is aimed toward students, the craft of medicine is not aimed at the healthy, but rather at those who are sick and in need of care. Such is the very nature of medicine. To emphasize this point, the Hipporatic Oath states, “I will follow that system of regimen which, according to my ability and judgment, I consider for the benefit of my patients, and abstain from whatever is deleterious and mischievous.”

The Doctor finds a radically different set of values on the alien medical ship. He initially encounters unacceptable (to human standards) medical conditions in what is known as “level Red.” Patients are not being given the necessary treatment or prescriptions because their “TC,” or “treatment coefficient,” is not high enough. An individual’s TC was designated by the allocator, the planet’s main administrative computer system. The level of a person’s TC was determined by factors such as education, skill, wealth and overall ability to be a “producing” member of society. The Doctor is appalled at the notion of withholding treatment from individuals on the basis of socio-economic standing. However, he is such an effective healer with his Federation knowledge that he is quickly transferred to “level Blue."

Level Blue is a different world. Whereas level Red was overcrowded, dark, unsanitary and lacked the necessary resources to provide adequate care, level Blue is clean and spacious with only a few patients resting comfortably in plush medical beds. Moreover, many of the patients here, with a supposed high societal value, were not even sick. They were receiving preventative care for illnesses they did not have with the same medicine that would save lives on level Red. The medical care on level Blue was second to none with all of the resources imaginable. The only caveat was that to be a patient you had to have a certain social standing based on societal usefulness.

However, the system that determines societal usefulness was flawed. The young man Tebbis was particularly gifted with medical knowledge and displayed proficient practical skill in diagnosis and treatment. However, he was not a member of a socio-economic community that could afford his formal training and provide opportunity for him to explore his talents. Hence, his TC was low because the way Dinaali society discovered and nurtured personal potential was shaped by social factors external to that individual potential. In other words, Tebbis’s medication would not be allocated to him because of his social status. This status had little to do with his desires, drive or talents, and much more to do with a lack of opportunity. One cannot be formally trained if one cannot afford the training.

Chellick is unsympathetic to the complaints of the Doctor regarding level Red patients. Chellick inputs data into the allocator and does not take responsibility for the results. He is also insulated from having to experience the hardship and neglect that level Red patients experience daily. He inputs the data and administers the rules. He does not think he has a moral obligation to provide better care for level Red patients. The Doctor gives Chellick a taste of his own medicine by infecting him with the same disease that eventually killed young Tebbis. It is only when Chellick has to experience unstable healthcare in his own system that he changes. It is only when he is no longer able to isolate himself from the rules of the allocator that he acquiesces.

What the Doctor sees clearly is that the kind of medicine provided in the Danaali hospital is actually a violation of the medical craft. This system fails to see that the object of medicine is the sick, not the wealthy – those in need of care rather than those who can afford to receive it. The Doctor’s programming with the Hippocratic Oath provides the ethical basis upon which he understands his vocation as a physician and what types of administrative and distributive procedure violate that vocation and prevent him from carrying out his craft. The tradition of medicine that has guided medical ethics from Hippocrates to 24th century was stymied by the allocator and administrative apparatus put in place to portion out care.

At the end of the episode, the Doctor is concerned that his own ethical subroutines are faulty because of his willingness to infect Chellick in order to bring about institutional change. Seven of Nine disappoints him in confirming that his ethical programming was sound and without need of repair. The Doctor confronts the tension between his responsibility to an individual patient, and the desperation of a planet filled with people who are sick and denied care because they are considered less useful by an administrator. It was not simply the difference between a patient he created and the patients who needed him. The Doctor’s ethical subroutines were not flawed – he did what the demands of his craft dictated. He was there “for the sake of the sick,” as Hippocrates would advise.

I would like to thank my colleague, Michael R. MacLeod, both for his helpful suggestions and comments on this piece and for his camaraderie in all things; especially those pertaining to Star Trek.

Timothy Harvie is Associate Professor of philosophy and ethics at St. Mary's University in Calgary, Canada. His interests lie primarily in philosophical theology, political philosophy, environmental and animal philosophies, and ideas of the role of hope in society. He is a lifelong Star Trek fan. http://www.stmu.ca/dr-timothy-harvie/