Published Apr 23, 2022

Finding Star Trek at the Seder Table

"Let my people boldly go..."

StarTrek.com

A massive, slowly spinning space station poised at the entrance of the Celestial Temple and a table (or Zoom call) surrounded by people all leaned to the left: at first glance, these two things appear to have little to nothing in common. However, much of Trek’s deep ethical underpinnings either root themselves in Judaism (beginning with that famous hand gesture, explicitly derived by Leonard Nimoy from Rosh Hashanah’s priestly benediction) or run parallel to those ideals. Passover showcases this closeness beautifully. From dramatis personae to storylines and philosophy, it’s easy to find Trek at the Seder table.

Every year, observant Jews around the world gather during Passover to eat a festive meal together and read the seder (“order”). Many different versions of the seder exist, written in haggadot (“tellings,” singular haggadah). Some fall very closely in language and format to the earliest modern haggadot, dating from the 13th century. Others range in content and audience from children’s books to humorous takes on the seder to LGBTQ+ focused. The 14 steps of the seder lead us through retelling how Moses (and Aaron and Miriam) lead the Exodus from Egypt.

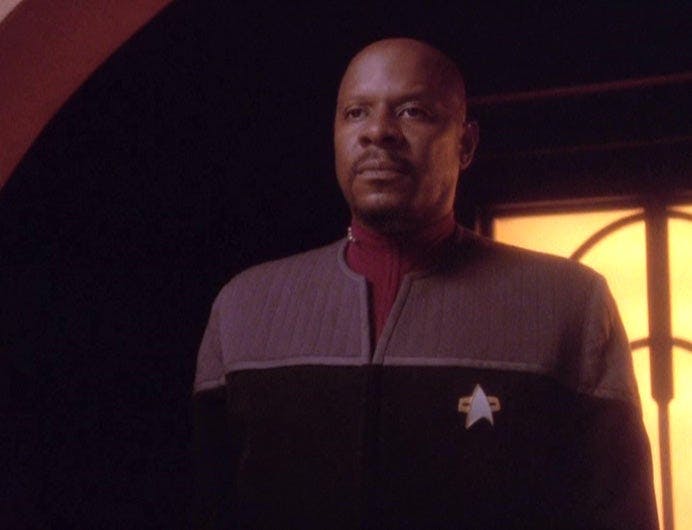

Moses predictably takes center stage in the seder’s story. A reluctant religious leader, Moses protested his fitness to take on the role God asked of him but became the leader of a tribe in whose culture he hadn’t been raised. He led them through long and sometimes violent trials, unable at the end to enter the peaceful era after those trials with the rest of his family and loved ones. We don’t have to stretch much to find Trek’s Moses in Benjamin Sisko’s repeated refusals of his role as Emissary before he reluctantly assumes that mantle.

On Passover, like Sisko we come to understand it is not linear: every time we sit down at a seder table, we join a chain of celebrations leading back at least 2500 years. During Maggid, the fifth section of the seder, we retell the story without separating ourselves from the action. We don’t say they left Egypt—we say we left Egypt. We recognize ourselves as part of that ongoing story of liberation while reinforcing the truth that we have not completed that work. Just as Sisko understood that he kept returning to the moment when he lost Jennifer, and that this moment shaped everything which came after it, we understand that we return to Passover every year. Our history prepared us for the Exodus, and the way both the trauma of Egypt and the first moments of freedom shaped us continues to guide us as a people.

StarTrek.com

From that moment sprang a people constantly striving. Jews know that we don’t have all of the answers to how the universe works, or what G-d wants from us. We constantly seek the right way to do something, looking for the next set of answers. When it comes to solutions and knowledge, we always boldly go. We’re so fixed on continuing to explore questions of ethics and truth that one of our foundational documents, the Talmud, usually comes printed in 40 volumes – and if there’s room in the margins, my first rabbi told me, there’s room for your commentary in the Talmud, too. The universe is big, beings are diverse, let’s find out what's out there and let's always question what the 'right way' to do something is. That is Starfleet at its best, too.

Passover is all of this, but doubly so. We hadn't yet had the Golden Calf, 40 years in the desert, the loss of Moses, and everything that came after. What we had in our hands during the first Passover was this amazing freedom, this wide-open world unfolding in front of us, when generations of fear and oppression lifted and suddenly what we had was a horizon stretching out in front of us. And even then, even in that moment, we were very conscious of who we were, where we came from, what our freedom cost. Hundreds of years later we built our remembrances into a ceremony so we would both remember that freedom comes from resistance, and not forget everything it took.

That, too, is Trek: looking forward while not forgetting what got us to this point. And in Passover we find perfect examples of how we continually strive for better and more understanding. People add items to the seder plate to represent people important to the story. Additions over the last few decades include Miriam’s Cup sitting next to Elijah’s to honor the role of women in Jewish society, an orange for LGBTQ+ rights, and acorns to weave Indigenous land discussion into our Seder observations as part of a larger discussion on teshuvah, working toward greater justice and reparations in these matters and others. We write new Haggadot which seek to incorporate the whole of our experience and all our interlocking identities, like the LGBTQ+ Haggadah I have which still requires yearly updates because we read out the names of the past year’s victims of transphobic violence instead of the names of the plagues. We take drops of wine out of our cup to symbolize the lessening of our joy as we mourn those who our community has had violently taken from us.

StarTrek.com

When seeking a Trek proxy for Passover’s anger and grief, Jews need look no farther than Bajorans, especially as typified by Major Kira Nerys. At the beginning of Deep Space Nine, Kira finally has the freedom she fought for all her life. She has that open horizon (or that freed planet) she struggled for. The tension between her time in labor camps and the new freedom she finds after liberation form the backbone of the rest of her life. Kira is defined by her struggle for liberation and how to live justly in this new, fully independent world once she finds it.

In the book of Exodus, two midwives, Shiprah and Puah, lie outright to Pharoah’s face to protect the lives of Israelite boys (including Moses). One of the Mishnah (basically “rabbinical headcanons”) states those names were the noms de guerre of Miriam and Yocheved, Moses’ sister and mother. With that in mind, Kira fits neatly the role of Miriam. It’s easy to picture her staring Pharoah down and saying without blinking that Israelite mothers are just too darn good at this whole “having babies” thing, so they can’t get to birthing beds fast enough to verify the newborn’s gender. Miriam follows Moses down the river, hides in the reeds, and then bold-facedly lies again (this time by omission) to Bithiah, daughter of Pharoah, so this self-appointed undercover agent can bring back Yocheved to act as Moses’ nurse.

Moses and Aaron’s partner in leadership, our traditions say Miriam’s righteousness brought us the manna in the desert, the pillar of fire to lead us, and our water in the desert. We see the strength of the women who carried us through the desert in Kira, from her partnership with the Moses figure of Sisko to her challenging of our Aaron figure: Kai Winn.

StarTrek.com

A leader in his own right, Aaron struggles with doubt and his desire for controlling the uncontrollable. Completing the triumvirate who led us through the Exodus, he acts in compliance with everything ever asked of him if Moses is there to provide explicit instructions. The moment there’s no one to give him directions – when Moses goes up the mountain – we see him fall into doubt, leading to the construction of the Golden Calf. Similarly, every time Kai Winn finds herself faced by a choice in which either her faith or her fear can rule, her fear gets the upper hand. Her tight grip on any form of control over her environment comes from the trauma she suffered during the Occupation just as fully as Kira’s bold righteousness comes from hers, and whenever she loses that control, Kai Winn acts rashly out of fear.

When we sit at the seder table, we know comes next in this story: yes, we’re free, but the hard part’s just beginning, whether that’s the work of finding a land to make our homes in or cleaning up what the Cardassians did to Bajor. We may find ourselves tempted to let fear rule us so that we do not boldly go forward into the future but instead shrink back from the challenge of creating a better, more beautiful world that celebrates life in all its infinite diversity. Passover challenges us to reject that fear.

The seder is neither linear nor static. It reaches back into the past and looks forward into the future. Like Star Trek, Passover shows us our history of striving for better as a people, while acknowledging that we may not see a perfect world within our lifetimes. We may never achieve the justice and freedom the seder calls on us to strive for, but Passover lays out our continuing mission.

Star Trek: Deep Space Nine — The Journey

Spider B. Perry (he/they) lives in Portland and runs NerdyKeppie.com with his partners, daughter, and 4 rescue pit bull mixes. Find them talking endlessly about disability, LGBTQ+ history and why Sisko is the best captain at @vaspider on Twitter.