Published May 21, 2013

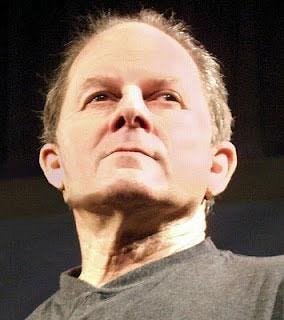

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: STID Novelization Author Alan Dean Foster, Part 1

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: STID Novelization Author Alan Dean Foster, Part 1

Your return to the Trek universe for the Star Trek (2009) novelization was 30 years in the making. How did it come about? Were you surprised they approached you?FOSTER: That’s easy. They asked me. Was I surprised? Yes and no. I was surprised because it had been so long. I was not surprised because I’d been doing book versions of movies all through those decades right up and through to films like The Chronicles of Riddick. So it’s not like I’d been away from the work, but I’d just been away from Star Trek.

Do you think the fact that you worked on the novelization of Transformers, which was an Orci-Kurtzman script, had anything to do with you getting the call for Star Trek (2009)?FOSTER: You’d have to ask Bob (Orci) that. I didn’t meet with Bob or Alex (Kurtzman) while I was doing the Transformers novelization, but I did meet with Bob prior to finishing the novelization of the 2009 version of Star Trek. So, obviously, they were pleased with the novelizations of the Transformers films, plus the original novel I did to bridge them, or they wouldn’t have contacted me, regardless of any other factors, to do the Star Trek film.How were you approached about doing Star Trek Into Darkness?FOSTER:

amon Lindelof during the process of writing this novelization? Or did you just work from the script you were handed?FOSTER: I always start with the script. Also, in the case of this one and the previous films, I was fortunate enough to be able to see the ed for me himself, specifically, but I have no confirmation of that. I’ve never met J.J. I just watch his movies. But, obviously, everyone concerned was pleased with the books version of the 2009 movies, so no one raised any objections to my doing the latest movie.To you, what is at the heart of Star Trek Into Darkness?FOSTER: It’s all about personality conflicts. There are people who love science fiction who will say it’s insufficiently science fiction, and there are people who will say that’s what makes Star Trek great, and always has. For me, good writing and good story has always been centered on characters and everything else, however well developed, is window dressing. Certainly, Star Trek Into Darkness, if anything, is even more character-centric than the previous film.Did you have access to Orci, Kurtzman and Damon Lindelof during the process of writing this novelization? Or did you just work from the script you were handed?FOSTER: I always start with the script. Also, in the case of this one and the previous films, I was fortunate enough to be able to see the film as it was being made and edited. That, of course

sing. Certainly, Star Trek Into Darkness, if anything, is even more character-centric than the previous film.Did you have access to Orci, Kurtzman and Damon Lindelof during the process of writing this novelization? Or did you just work from the script you were handed?FOSTER: I always start with the script. Also, in the case of this one and the previous films, I was fortunate enough to be able to see the film as it was being made and edited. That, of course, is an enormous help, which I’d almost never previously had when doing novelizations. I was very grateful for that. I had a long chat with Bob in his office at Universal. I expressed some thoughts and he came back (with his thoughts). It was a very unusual project. Usually, the people making the film have either very little interest in the book version or the interest they have is solely critical. And, in this case, there was considerably more back and forth than you usually get, which I think results in a better book.Scenes in movies are shifted around, trimmed down and

ake a bad mistake, if I describe the wrong color of uniform, somebody will catch it and say, ‘Nope, this isn’t right.’ That happened with the previous Star Trek novelization and with this one. Sometimes I would have to expand upon a scene and invent something and then they’d come back and say something. For example, I had the character Keenser, who is the little alien who is Scotty’s assistant, talking. I gave him some dialogue, which I thought would an interesting way of expanding his character. The scene in the bar with the two of them, Scotty is just bouncing his misery off Keenser. Keenser doesn’t say anything. He just stares back at him. I originally had given Keenser some dialogue. I forget who was vetting things at the time, but I got a note saying, “Keenser doesn’t speak in the film. Can you please take the dialogue out?” I was happy to do that because I wafortunate enough to be able to see the film as it was being made and edited. That, of course, is an enormous help, which I’d almost never previously had when doing novelizations. I was very grateful for that. I had a long chat with Bob in his office at Universal. I expressed some thoughts and he came back (with his thoughts). It was a very unusual project. Usually, the people making the film have either very little interest in the book version or the interest they have is solely critical. And, in this case, there was considerably more back and forth than you usually get, which I think results in a better book.Scenes in movies are shifted around, trimmed down and sometimes edited out entirely as a film comes together. How fluid a process does a novelization have to be?FOSTER: It is fluid, but in the earlier days of both films and novelizations there was no time for these things. There was no Internet for shooting things back and forth. There was no way for the author to communicate quickly with the people working on the film, even if they were so inclined, much less for the author to look at the film. Now, because of digital editing and the Net, things can be exchanged almost instantaneously. This is both good and bad. It’s good because you end up with a book that, in the final analysis, relates to the finished film as closely as possible. It’s bad because, as the author, I asked, even though I am not contractually obligated, to make the book match the finished version of the film as closely as possible. As a fan, however, I do feel a responsibility to include every last possible change right up until the final edit, in the book. What this means to me is a lot of last-minute, very quick rewriting, which I’m happy to do as a fan, if not even more so as a writer.You get to add a lot of subtext that a film simply cannot include. Let us give you an example in your STID novelization. During the volcano sequence, describing Sulu’s terse interaction with Uhura while Spock’s life hangs in the balance, you write, “Sulu outranked her. At the moment, he wished he didn’t.” That’s not in the film. The scene goes by so quickly, moviegoers might not even realize that Sulu feels terrible about the situation. Take us through your view on a scene like that…FOSTER: People think that one of the main things that novelizations do is to expand existing scenes. That’s true to a certain extent, but the fun part of it, and the important people of it, I feel, is to fill in the blanks. One of the biggest blanks in any existing film, assuming it isn’t 15 hours long, is to show what the characters are actually thinking. When they’re doing something on screen it’s just, well, “Sulu moved the lever forward.” That’s about as short a sentence as you can come up with. But I get to show what he’s thinking, why he’s moving the lever, what’s going on in his head while he’s moving the lever, what the possible consequences might be for moving that lever, and on and on and on. To me, that’s one of the joys of doing it. I get to make my own director’s cut, in other words.Does your director’s cut need to tie into Abrams’? Does somebody need to sign off on it because, especially in the world of Star Trek, in the eyes of hardcore fans, what’s in that book will be canon? You know that better than anyone…FOSTER: I’m fairly familiar as far as what’s canon, but your point is still well taken. Yes, everybody needs to sign off on it. People review it and they come back and they said, “Well, can you do more of this” or “Can you take this out?” or ‘You can’t do this because in the next cut of the film we’re going to change this scene.” When you have something like Star Trek or Star Wars or Transformers, where people obsess over the smallest details, if you are interested in what you are doing beyond just making money, then, yes, you want to make sure that everything fits as closely as possible to existing canon. I try to do that on my own, and I know that there are people backing me up who will check on it. If I make a bad mistake, if I describe the wrong color of uniform, somebody will catch it and say, ‘Nope, this isn’t right.’ That happened with the previous Star Trek novelization and with this one. Sometimes I would have to expand upon a scene and invent something and then they’d come back and say something. For example, I had the character Keenser, who is the little alien who is Scotty’s assistant, talking. I gave him some dialogue, which I thought would an interesting way of expanding his character. The scene in the bar with the two of them, Scotty is just bouncing his misery off Keenser. Keenser doesn’t say anything. He just stares back at him. I originally had given Keenser some dialogue. I forget who was vetting things at the time, but I got a note saying, “Keenser doesn’t speak in the film. Can you please take the dialogue out?” I was happy to do that because I wanted the scene in the book to accord with the scene in the film. So somebody is always there to check on such things. Now, that doesn’t mean nothing can slip through the gap, but it certainly makes the book and the film match up a lot better than if nobody was checking on it.Click HERE to purchase Foster’s Star Trek Into Darkness novelization. And click HERE to visit the author’s official site.