Published Jun 4, 2024

Adam Nimoy Pens New Memoir 'The Most Human: Reconciling with My Father, Leonard Nimoy'

Read an exclusive excerpt from the memoir, available everywhere books are sold today!

StarTrek.com

From Adam Nimoy, get an inside look behind his relationship with his father in his memoir, The Most Human: Reconciling with My Father, Leonard Nimoy.

This hardcover, available now everywhere books are sold like Bookshop, Barnes & Noble, and Amazon, tackles the universal lessons of recovery, becoming a better father to your children by healing your relationship with your own father, and a peek behind the curtain at a childhood growing up with an entertainment icon.

Chicago Review Press

While the tabloids and fan publications portrayed the Nimoys as a "close family," to his son Adam, Leonard Nimoy was a total stranger.

The actor was as inscrutable as the iconic half-Vulcan science officer he portrayed on Star Trek, even to those close to him.

Now, his son's poignant memoir explores their complicated relationship and how it informed his views on marriage, parenting, and later, sobriety. Despite their differences, both men ventured down parallel paths: marriages leading to divorce, battling addiction, and finding recovery. Most notably, both men struggled to take the ninth step in their AA journey: to make amends with each other.

Discover how the son of Spock learned to navigate this tumultuous relationship — from Shabbat dinners to basement AA meetings — and how he was finally able to reconcile with his father — and with himself.

Thanks to our friends over at Chicago Review Press, StarTrek.com has an inside look at The Most Human: Reconciling with My Father, Leonard Nimoy!

SPOCK AND SPIDEY

On a Saturday morning in the fall of 1966, when I was ten and Star Trek had just gone on the air, I went with my dad to Hollywood on one of our father-son outings. It was an annual tradition we'd started the year before where we'd drive to M'Goos — an old-school pizza parlor on Hollywood Boulevard — then head over to the Cherokee Book Shop, where Dad would buy me some vintage comics. It was a tradition that occurred exactly twice before being abandoned, which was something of a relief, as I never knew what to say to him when we were alone, and he barely said anything to me. In this respect, my dad was exactly like his father, my grandfather Max, a man of few words if any. Oftentimes it felt like Dad and I were strangers, always struggling for something to say.

"I like the sawdust on the floor," I said.

"Yeah, it's good," Dad replied. Then, nodding toward the waiters in their straw hats and red vests, "What do you think of their uniforms?"

"Yeah, they’re neat," I replied.

Despite our discomfort, I loved M'Goos — it had an authentic old Hollywood feel to it not unlike Musso & Frank, a dining landmark right down the street. We were at M'Goos in the late morning before the lunch hour, and the place was practically empty. Had it been busier, people would've been coming up to the table to ask for autographs, something that had been happening regularly over the past few months as Spock's popularity grew. One time Dad took me to a carnival at St. Timothy's Church on Pico and Beverly Glen. He was immediately mobbed, and that was the end of that. With no fans around at M'Goos, we just sat there in our awkwardness. I was glad when the pizza finally arrived because it gave us something to do. And it was delicious.

After we ate, it was off to the Cherokee Book Shop. Finding the collectible comics section at Cherokee was like discovering hidden treasure. You had to walk to the back of the store, then up a narrow staircase that led to a secret attic hideout. A humorless hippie named Burt ran the comics section, which was a small room of wooden bookshelves stacked with cardboard boxes filled with classic, colorful editions from DC and Marvel. There were sample comics in plastic bags taped to the front of each box — Batman, Justice League of America, The Atom, The Fantastic Four. The place was a mecca of comic book art and storytelling. It was there that I picked up old copies of Daredevil and Green Lantern, and my all-time favorite — The Amazing Spider-Man. So satisfying to sift through those boxes and find back issues with killer covers of Spidey being tormented by Green Goblin, Sandman, and Doc Ock. I could relate to that fatherless loner Peter Parker.

Dad and I didn't spend much time together in those early days. Before Star Trek he was constantly working odd jobs and pursuing bit roles in TV shows, a remnant of the work ethic forged on the Depression-era streets of Boston, where he was born and raised. My dad was a man obsessed with paying the bills while pursuing his passion. When he got his big break costarring on a new science fiction TV series on NBC, I barely saw him at all. I knew Dad had brought me on a father-son outing to Hollywood because he felt he should, because he wanted to be a good dad. But as was typical, he was distracted and withdrawn that day at the Cherokee Book Shop. We were in a room filled with one of the best sci-fi/fantasy comic book collections in the country, and the man who had appeared on The Outer Limits and The Twilight Zone, and was now making a splash as Mr. Spock on Star Trek, leaned against a wall and waited in detached silence. Sometimes, I simply could not figure the guy out. I remember feeling this unspoken pressure to decide what I wanted so we could get the hell out of there.

"And his own sensibility, it seems safe to say, informed [his] character." So read the obit in the New Yorker after Dad died in 2015.

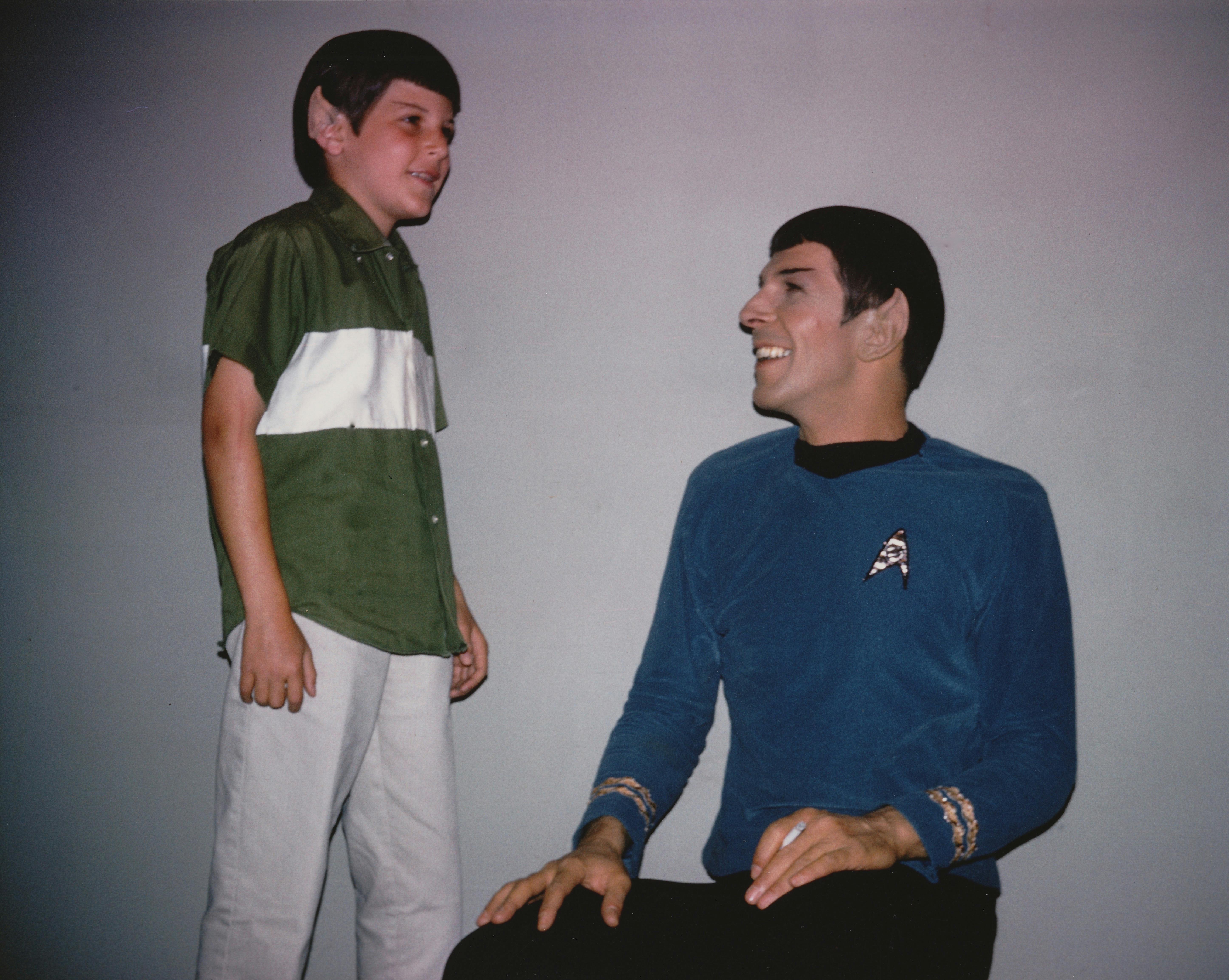

Courtesy of Adam Nimoy

It was definitely safe to say. Like Spock, my father was often inscrutable — it was hard to know what he was thinking or feeling. The similarity to the half-human, half-Vulcan science officer didn't end there. Like Spock, Dad was not the warm and fuzzy type. One of my earliest memories of him was when we were living in our tiny first house on Palms Boulevard in the Mar Vista neighborhood of L.A. I must have been five or six years old. It was morning, and Dad was wearing a suit because we were going to High Holy Day services. We were waiting for my sister and my mother when dad showed me a magic trick. He tucked a small rubber ball into the upper part of his sock and, with a wave of his hand, made it disappear.

Wow, I thought. Daddy can do magic! Then I had this weird sensation. While I was standing there in awe, I was waiting for him to give me a hug or a kiss. My mother would have done it. Her parents, Grandpa Archie and Grandma Ann, would have done it. But Dad didn't. I had this feeling that he was almost like a stranger to me, as if he were a long-lost uncle who came to visit and showed me a little magic and that was that. My mom would later tell me that when my sister and I were babies — my sister Julie is a year and a half older than me — Dad was much more hands-on helping to take care of us. We even have some old 8 mm film showing Dad giving us baths and holding us during outings. But by the time I was old enough to start remembering things, I felt this distance from him.

There's another memory about my dad that's stuck in my mind, something that happened when I was a little older, probably when I was seven or eight. I was standing in the kitchen of our second house, on Comstock Avenue in West L.A., while my mother was looking for something in the refrigerator. Dad came in to fix himself a drink. It was the afternoon, and I watched as he made himself a martini with a lemon peel. He then shuffled off to the bedroom, drink in hand, leaving the bottles and the lemon and the knife on the counter. It was just an ordinary weekend afternoon that I never would have remembered, except for the fact that, seeing the mess he left behind, my mother pulled a milk bottle out of the refrigerator, lifted it over her head, yelled my father's name, and threw it against the countertop. It shattered on the avocado-green tile. I ran out of the kitchen and into the living room, where I hid under the coffee table, whimpering. My father came into the room and sat in a chair. He sat there and said nothing. I crawled out from under the table and into his lap. He reluctantly put his arms around me. Years later when I read about Dr. Harry Harlow's "monkey love experiment" for some psychology class, I flashed back to that day, because it felt like I was one of Dr. Harlow's baby monkeys trying to get comfort from a parent made of bare wire.

I had so much trouble bonding with Dad when I was a kid, which isn't to say he didn't try. In the winter of 1968–69, not long after we moved into our third and final house in the neighborhood of Westwood, Dad returned home from an out-of-state personal appearance, which was something he often did on weekends, because it gave him a chance to interact with the fans. And it generated fast cash. I was in my room when he came in and handed me a small box containing a colorful set of Mr. Toad cuff links and tie clip. The set was clearly made for a little boy, but I was twelve at the time. It didn't matter, because I was so grateful for the gift. My father had thought to buy me something while he was away. I never wore the Mr. Toad cuff links or tie clip, but I adored them.

Dad also took me fishing back in the day when there was a huge barge anchored way out in the Santa Monica Bay. And sometimes we'd go sailing. He was an excellent sailor from his years growing up on the Charles River in Boston. He had a natural feel for the wind and the water and would give me clear orders when to switch the jib sail when he was turning the boat. I remember one day we were at the rental office at Marina del Rey and it was windy as hell. The guy at the desk had just said to the people in front of us that he was only outfitting the boats with mainsails. Then he turned to Dad and said, "Mr. Nimoy, you know how to handle yourself out there, so I’m going to also give you a jib."

I always felt secure with Dad when we were doing these kinds of activities, whether we were sailing a boat in rough conditions or he was flying his single-engine Piper aircraft through a rainstorm.* He had a focus and a confidence that put me at ease. Then again, sailing with him was more of a meditative experience than an opportunity for us to connect. And sitting for hours in a noisy cockpit with his eyes fixed on the controls or searching the sky at ten thousand feet was not exactly conducive to conversation. This was the difficulty I had with my father: there was always an emptiness between us — we were missing a deep emotional connection. He sometimes told me that he loved me, but it was so hard to feel it. We never watched TV together, never played catch. He never came to my Little League games. Except for our occasional excursions, we never hung out together. It just wasn't his thing. But I was always proud of him.

* Dad learned to fly in London in 1972 while making a forgettable TV movie. Once he earned his instrument rating, I could never get him back in a boat. Star Trek III actually grounded him for a while, when the insurance company said no to the film’s director and star tooling around in the air. Years later, when his plane’s retractable nose gear refused to go down and he had to skid to a stop on the landing strip, that’s when he hung up his pilot’s goggles.

Courtesy of Adam Nimoy

Even before Star Trek, I'd see him popping up in bit roles on my favorite TV shows like Get Smart, Sea Hunt, and The Man from U.N.C.L.E. Wow, I'd think. That's Dad! I remember one Saturday afternoon in the early '60s, I was at home watching a low-budget thriller called The Brain Eaters. I could tell it was a cheesy film, but there were only six channels back then and there was nothing else worth watching. Roger Corman, the king of cult movies, was one of the producers, as was Edwin Nelson, a friend of Dad's. Ed had brought his family to a party my parents threw when we were living on Palms Boulevard. He would go on to costar in the highly successful prime-time soap Peyton Place, but in those early days, in the "struggling actor" days when Dad was hustling all sorts of odd jobs, Ed got him a job as a process server. The two of them would hide in the bushes then jump out and serve people with court papers.

In The Brain Eaters, alien parasites have infiltrated the small town of Riverdale, Illinois, and have managed to attach themselves to — wait for it — people's brains. It was a typical black-and-white horror movie featuring "crawling, slimy things terror-bent on destroying the world!" Ed coproduced and starred in the film as Dr. Kettering, the lead investigator who finds a spaceship-type structure that has let loose the parasites. Fearlessly climbing inside, he finds a bearded man named Cole who seems to be in control of the brain eaters. The actor is wearing so much makeup he's unrecognizable, but the minute Cole spoke I was shocked to discover that it was Dad. I thought to myself, Holy cow, Dad is the king of the brain eaters! Then I yelled for my mother. "Mom! You gotta come see this!!"

That's the kind of acting work Dad was doing in the late '50s and early '60s: small parts in a few films and dozens of TV episodes. Then, one December night in 1964, he brought home some Polaroids of himself in makeup and wardrobe for a pilot episode he was working on. It was one of those I’ll never forget this moment moments, as he handed me the pictures, front and back shots of Mr. Spock. It was the early Spock, the primitive Spock: rough, uneven haircut, bushy eyebrows — and those ears. (Many years later Dad would explain to me that it was Charles Schram at the MGM makeup department who created the first foam latex prosthetics for Spock’s ears. Mr. Schram was best known for his work creating the prosthetic makeup for the Cowardly Lion and the Wicked Witch in The Wizard of Oz.)

Even in 1964, when nobody had heard of Star Trek, the eight-year-old me had watched enough Outer Limits and My Favorite Martian episodes to understand exactly what I was looking at. I mean, "The Galaxy Being," the first Outer Limits episode, had a huge impact on me. A scary but benevolent alien accidentally arrives on Earth and is misunderstood and treated badly — a sci-fi trope that always appeals to us outsiders and social misfits trying to find our way in a sometimes unwelcoming world. And now here was Dad playing the half-human, half-alien Mr. Spock, soon to take that trope to a whole new level. All these years later I can still feel the excitement I felt that night when I was given my first glimpse of this strange-looking man from outer space. (Miraculously, I still have one of those Polaroids of Spock backed with the inscription Leonard Nimoy Dec 1964.)

"This is what I've been working on all week," Dad said, obviously pleased by my reaction. It was a big moment for him, a costarring role in the pilot of a potential new TV series. In Dad's family his older brother Melvin was the star because of his academic career — something my father had no intention of pursuing. When Dad told his parents he wanted to be an actor, they were devastated. It was as if he had told them he wanted to join the circus. Dad always played a supporting role to my uncle, but now he was coming into his own, and I shared in the excitement of this new development. It was a way for us to connect on a deeper level, to have something that appealed to me as an avid fan of science fiction and to my dad as an artist striving to get to another level in his career.

Jonathan Melnick

There would be many more shared experiences related to Star Trek, like the time I was visiting the set and the crew decided to pull a prank on Dad by putting me in Fred Phillips's makeup chair, where he cut my hair, shaved my eyebrows, and glued on a pair of Spock ears. While Kirk was on the planet of the week and Spock was in the captain’s chair, the turbolift opened and out I walked onto the bridge. While I was in the turbolift waiting for those doors to open, I remember having another one of those I’ll never forget this moment moments. The episode was "What Are Little Girls Made Of?" — which was shooting in July and August 1966, over a month before the show even aired. Let the cosplay begin!

When I walked onto the bridge and kissed my father on the cheek, everyone on the crew started laughing. Dad smiled as if to say, Ha-ha, you got me again, because they were always pulling pranks on set, all of which showed up in the immensely entertaining blooper reels they screened at the Christmas parties. After our little prank, the crew broke for lunch and Dad and I went off to one of the Enterprise corridors to have our picture taken. It was a nice moment between us, because whenever I visited the set, he was otherwise typically all Spock, all remote, all distant.

Then there was the much-anticipated night of September 8, 1966, when Star Trek premiered. Our family drove to a friend’s house in Beverly Hills to watch the first episode, "The Man Trap," on a color TV. (The fall of 1966 was the first time all three networks aired their primetime schedules in color.) It was so powerful to see that first glimpse of Spock in the scene on the bridge with Lieutenant Uhura. She challenges him to lighten up and let his hair down while Captain Kirk's away on the planet, but Spock remains all business.

Not only was the New Yorker right that my father's own sensibility informed his character, but while they were shooting the original series there would also be this feedback loop. Dad later admitted that he found it difficult to get in and out of character during his three years on the original Trek series, which meant that during those years the withdrawn and detached attitude I had experienced from my father was now being amplified because of the character he was playing on television. As my sister Julie succinctly pointed out, during the Trek years Dad was simply unavailable.

After the premiere, the producers would regularly let the cast and crew out early on the day the show was airing so that they could all get home in time to see it. And so, on Thursday nights at 8:30 pm, my family would gather on my parents' bed to watch Dad in the breakthrough role that would change our lives — on our portable black-and-white TV.

Spock's immediate popularity prompted the fanzines to start writing about Dad's personal life, characterizing us as a "close family." Julie and I smiled for photos meant for thought-provoking articles such as Why Leonard Nimoy Hides His Two Children and Leonard Nimoy: Is My Wife's Love Enough for Me? My favorite was a headline splashed over a two-page picture of me and Dad: How Leonard Nimoy Tries to Cope with Teenage Sex and Dope.

Star Trek was canceled after three seasons in 1969, but that same year Dad replaced Martin Landau on Mission: Impossible, playing Paris, the master of disguise, for two seasons. So from 1966 to 1971, he was rarely around. At the end of each shooting day, he'd come home for dinner, learn his lines, and then crash before getting up at five thirty the next morning. That first season of Star Trek, he woke up to the sound and smell of coffee brewing. It was this ridiculous setup — a large coffee pot plugged into an old clock radio, all of which sat on a flimsy aluminum folding table next to my parents' bed.

On the weekends, Dad was often out of town making personal appearances. He was also busy with his recording career, which all started with Mr. Spock's Music from Outer Space, a kitschy album that I just loved. Weekends were also made for recovering from the work-week or working on home improvement projects, like the brick wall he built between the driveway and backyard. When Dad decided to leave Mission: Impossible in 1971, we were living in our last home in Westwood where he suddenly found himself with a little more time on his hands — just when I was entering the angst and angry phase of my teen years. That's when the awkwardness between us and our failure to find any deep connection led to bigger problems.