Published Jan 5, 2021

Different Like Me

How Data taught a girl with HSAM that being “different” isn’t something to hide.

StarTrek.com

Hi! My name is Anna, and I can’t forget.

I don’t mean I can’t forget just one thing or a few things. I can’t forget anything.

It’s not something I’ve trained myself to do. It’s not infallible, and I’m not an omniscient Q. I still have to ask myself short-term questions: “Why did I walk in this room? Where are my glasses? Where did I put my keys?” But the long-term things—the things that are stored somewhere deeper in my brain—are there to stay.

My family has long believed that I have highly superior autobiographical memory (HSAM), also known as hyperthymesia. If you haven’t heard that term before, HSAM is a form of neurodiversity. It causes people to be able to recall an unusually large number of things that have happened in their lives — from the most mundane to the extremely unusual. These memories are ever-present and highly detailed. Everything I see, touch, hear, taste, or experience in any way, good, bad, or neutral, is imprinted in my mind, and it plays back constantly, like a film reel — to the point where I can say that, on a Friday in late August when I was in kindergarten, I had chicken and rice soup for supper, at 7:03 PM, while I watched Bananas in Pajamas. The present is always glossed over with the past, until it, too, becomes a past that glosses over the next present.

Brief respite comes when I visit a place I’ve never been before. But, after I’ve been there once, that new place is no longer new. It’s marked by my presence, and, if I ever visit it again, all other experiences there involve mental pictures/videos of all the previous experiences, no matter how many there are. This includes both the mere facts and the “substance, the flavor of the moments.”

My life is always flashing before my eyes.

All this makes my mind a very busy place to live. Sometimes it’s a blessing, because it lets me relive and savor every little detail of my happiest, most beautiful days. But it’s less wonderful when my mind shows me pictures I’d rather not see. I don’t always get to choose which albums it pulls out to say, “Hey! Remember this?!”

For many years, my memory made me feel quite out of sync with a world full of a “forgetting” I’ve never experienced. I pretended to forget, so I would seem less different, less weird.

Episode Preview: The Mind's Eye

I have loved Star Trek since the first time my little four-year-old self stood still long enough to watch part of a TNG episode: “The Mind’s Eye,” 9:00 PM, a Monday in mid-July, 1996. (Yeah, I know, that’s quite an episode for a four-year-old to jump into Star Trek with, but that’s what was on!) The music, the sounds, and the images fascinated me, and, every time an episode started, I practiced reading by trying to figure out what the credits said. I was frustrated that I couldn’t decipher “Michael” or “Marina,” but, when Brent Spiner’s name popped up, my heart was so happy because I could read it! Of course… I thought it said “Brett Spinner,” but that’s not bad reading for a four-year-old!

Then, I got older, and watching Star Trek stopped being just about the colors, the pictures, the sounds, and trying to figure out how words worked. Now, I could understand what it meant, what each episode was actually saying to me.

That’s when I watched — really watched — “Encounter at Farpoint” for the first time.

And I heard Data say to Admiral McCoy: “I remember every fact I am exposed to, sir.”

My soul snapped to attention, thinking: “He does? Really?”

In that moment, I found in Data what is called a ‘kindred spirit.’ Data was different like me.

StarTrek.com

I started watching the TNG episodes even more closely because I wanted to know everything there was to know about Data. What was he like? What made his digital timing tick? Most importantly, how did he, an android whose positronic brain remembered everything, navigate a world in which he was out of sync—a world made to suit the needs and capabilities of organic lifeforms, who were unlike him? How did he handle being different, being “weird”?

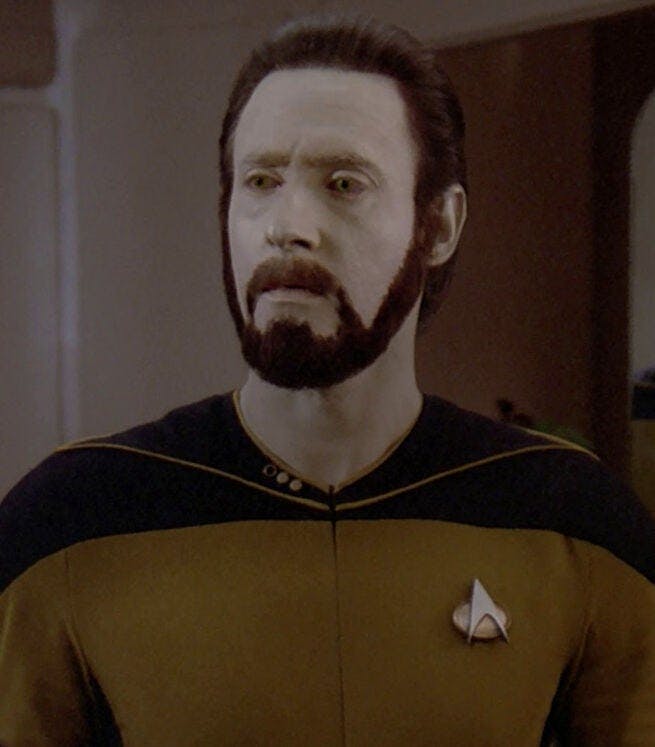

The more I watched, the more I saw that he navigated it remarkably well. Yes, he was different. He was a little endearingly eccentric sometimes (one of my favorite instances being in TNG’s “The Schizoid Man": “It is a beard, Geordi. A fine, full, dignified beard”).

StarTrek.com

But he made it. Day in and day out, he was doing this thing called life, and he was doing it well. He was loved. He was respected. He was accepted and valued as a Lieutenant Commander and as a friend. And his memory, speed, and accuracy were often what helped the “continuing mission” continue.

I have heard people question why Data idolizes Sherlock Holmes — a character so deliberately emotionless and so driven by logic, to the point of refusing to eat when he is working. After all, Data’s deepest desire is to feel, to experience the exact things Holmes purposefully rejects, to “taste his dessert.” But I get it. I really do.

We don’t always choose our heroes because they represent our visions of our ideal selves. Often, we choose our heroes because we see in them something that looks like us, exactly where we are—something that, fundamentally, is like who we are now, not who we would want to be if we could. We don’t always want paragons or the impossible to look up to. Often, we want the relatable, and we want people who make what feels impossible for us individually look a little bit more possible.

StarTrek.com

Sherlock Holmes is different like Data. In the absence of his emotion chip, Data can’t organically and spontaneously experience feelings the way he so desperately wants, but Holmes’s life shows him that he can still live fully, and have close friends (like Watson or Geordi), without the one missing piece that would make him consider himself more human.

Data is different like me. Data’s life has shown me that I was quite wrong to hide my differentness. Doing so didn’t make me any less different, but it did make me less “me.” Through Data, I found a very freeing path to personal acceptance, to embracing what makes me, “me.” And you want to know something? It wasn’t so terrible after all. I found that I had been my own problem. I was the only one who thought my memory was weird. These days, I can joke about it! When someone asks me a question, the answer to which is tucked away in one of my brain’s dustier storage files, I’ll give my best impersonation of Data sifting through his own memory banks while I fish around for the answer they need. (Okay, so, maybe it’s not the best impersonation, but it isn’t half bad for not actually being the Lieutenant Commander of Mirth, bah doom boom!)

StarTrek.com

This freeing acceptance is a gift, one of the first and one of many, that Star Trek has given to me. It has a similar gift for everyone. Out there, in all those lightyears and star systems, universes and timelines, there is someone — be they Captain or Klingon — who is different like each of us. That’s part of what makes Star Trek so captivating and so personal. It may be the most important part. Those heroes equip us to accept, even enjoy, who we are. We can then project that acceptance outward to strive toward making the kind of world Star Trek believes can exist. It’s a very different world than what we know now, but I believe we’re inching closer to making it reality.

I have a Hallmark itty bitty of Data, who has become one of my most treasured possessions.

StarTrek.com

I like to keep him with me. Most days, he sits beside me, on top of the curio cabinet, peeking over my left shoulder. He’s sitting there as I type this.

That little four-year-old lover of Star Trek grew up to be a writer of fiction herself. Each day, during those precious writing hours, I smile at my itty bitty Data, and, as his little embroidered mouth grins back at me, it feels like a passing of the torch. The pen is in my hand. It’s my turn to try my hardest to build places where the relatable, which makes the impossible seem a bit more possible, can exist. Will something I create one day impact another’s life the way Data touched mine? I don’t know. I certainly hope so. But I do know that this is how I’ve been equipped to help make that better world we see through Star Trek, “and the effort yields its own reward.”

My name is Anna. I remember everything, and, as Data taught me, that’s okay.

The world needs people who are different — like you and me.

Thank you, dear Data.

Data, What Are You?

Anna Elizabeth Gant (she/her) is a writer, academic editor, and summa cum laude (4.0 GPA) graduate of Regent University, who is completing her master’s in English at the University of Nottingham. Her most recent children’s novel is currently being reviewed by a UK publishing house. Find her on Twitter @Anna_E_Grant.