Published Nov 24, 2020

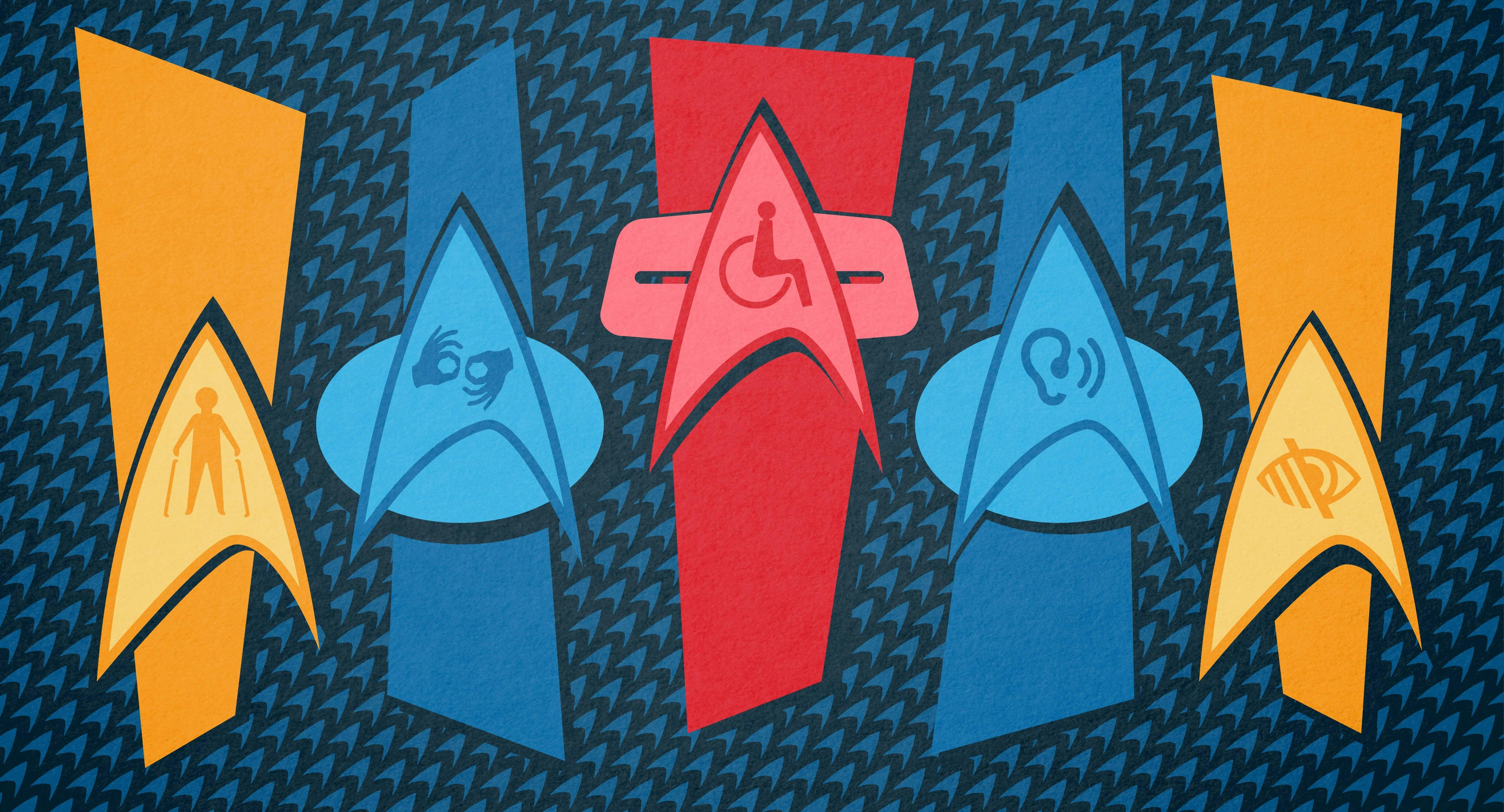

Deep Space Nine Still Had a Melora Problem — But We Shouldn't

Both today and in the future, accessibility should be a priority for everyone

StarTrek.com | Getty Images

“The truth is there is no ‘Melora’ problem. Until people create one.” (“Melora,” DS9, S2, E06)

When stellar cartographer Melora Pazlar decides to leave her low-gravity homeworld to join Starfleet, she adapts to higher gravities by using a wheelchair and braces. On a mission to DS9, she has difficulty navigating the Cardassian-built space station, which isn’t up to Starfleet’s design standards. The problem isn’t only with DS9’s physical spaces. The crew treats Melora differently than they would a non-wheelchair user as well. Dax discusses how inspirational Melora is, Bashir wants to “fix” her, Sisko consults Bashir on her medical fitness without including Melora. The crew displays ableist attitudes, and Melora calls them out on it. She refuses to be belittled and demands respect. Many disabled folk experience similar ableist sentiments. This episode shows the problems with using a medical lens only when viewing a disabled person. What needs to change isn’t Melora herself, but rather her physical and social environments.

Sara Goering explains the social model of disability in her scholarly article “Rethinking Disability: The Social Model of Disability and Chronic Disease”: “For many people with disabilities, the main disadvantage they experience does not stem directly from their bodies, but rather from their unwelcome reception in the world, in terms of how physical structures, institutional norms, and social attitudes exclude and/or denigrate them.” Goering does not negate the need for medical attention if needed or desired; instead, she argues for a more nuanced approach to treating disabled folk beyond the medical.

StarTrek.com

Everyone moves in and out of abilities. We become ill, we require glasses, we use crutches, we take medications, we have surgeries. We all require accommodations at multiple points throughout our lives. Society considers it a disability when the condition is long-lasting and lacks socially acceptable accessibility. For example, I require glasses to see. This condition is long-lasting and requires constant accommodation in the form of glasses. Yet, it’s typically not considered a disability because poor eyesight and wearing glasses have become normalized in a way wheelchair-use has not. If I lived in the 17th century, my poor vision would be much more debilitating because of the lack of accommodations. What creates the disability isn’t the wheelchair user; it’s a lack of accommodations and social perceptions surrounding wheelchair use. This is the difference between viewing disability through a medical lens versus a social lens. In the medical lens, the disabled person needs to be fixed, and the impetus for change is placed on their bodies. In the social lens, disability is a social construct created from stigmatization and a lack of accommodations. The impetus for change is broader and more inclusive.

Part of Bashir’s fascination with Melora stems from his desire to “fix” her. However, the cure he discovers would prevent her from returning to her homeworld. When she refuses his cure, he’s disappointed. This desire to “cure” or “fix” a disabled body often belittles the disabled person. Many disabled folks don’t want or need a cure. As disabled activist Wendy Lu argues, “Cure-focused narratives promote the harmful idea that disabled people’s bodies and lives are less valuable because of their identity.” While Bashir’s status as a doctor may make it logical for him to want to cure her, he fails to see Melora as a person. Melora did not ask for treatment or a cure because she knows nothing is wrong with her body. The issue is with Bashir’s perception of her body as being faulty.

StarTrek.com

I have an invisible disability called postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), and because of it, I cannot drive and have difficulty walking up and down stairs without becoming dizzy and occasionally fainting. No medication directly treats POTS, and the medications doctors tend to prescribe make me feel worse. I would rather have my body as is, but more accommodations in society would be nice. I daydream about transporters, and how easy it would be for me to buy groceries or visit a friend if only I had a transporter installed in the house. Of course, if I lived in a city with reliable public transportation, I wouldn’t need transporters or to bother friends and family for rides. If there were less of a stigma against non-drivers, I wouldn’t feel guilty asking for rides, and I wouldn’t be mocked for doing so (yes, this happens regularly). Similarly, if DS9 had been installed with ramps and wide aisles, and Dax, Bashir, and Sisko had respected Melora as an equal rather than pity her or praise her for “rising above” her disability, her experience on DS9 would’ve been very different.

The thing about these accommodations is that once in place, they tend to benefit everyone. On a space station that welcomes many alien species, ramps, wide aisles, and other accommodations would be extremely helpful, and I’m sure parents using a stroller to walk their child around the station would also appreciate them.

I’m not saying disabled folk shouldn’t seek treatment if they want it. They, of course, should, and many disabilities require constant medical aid. However, there’s a difference between treatment and the attitude that bodies that look too “different” should be “cured.”

StarTrek.com

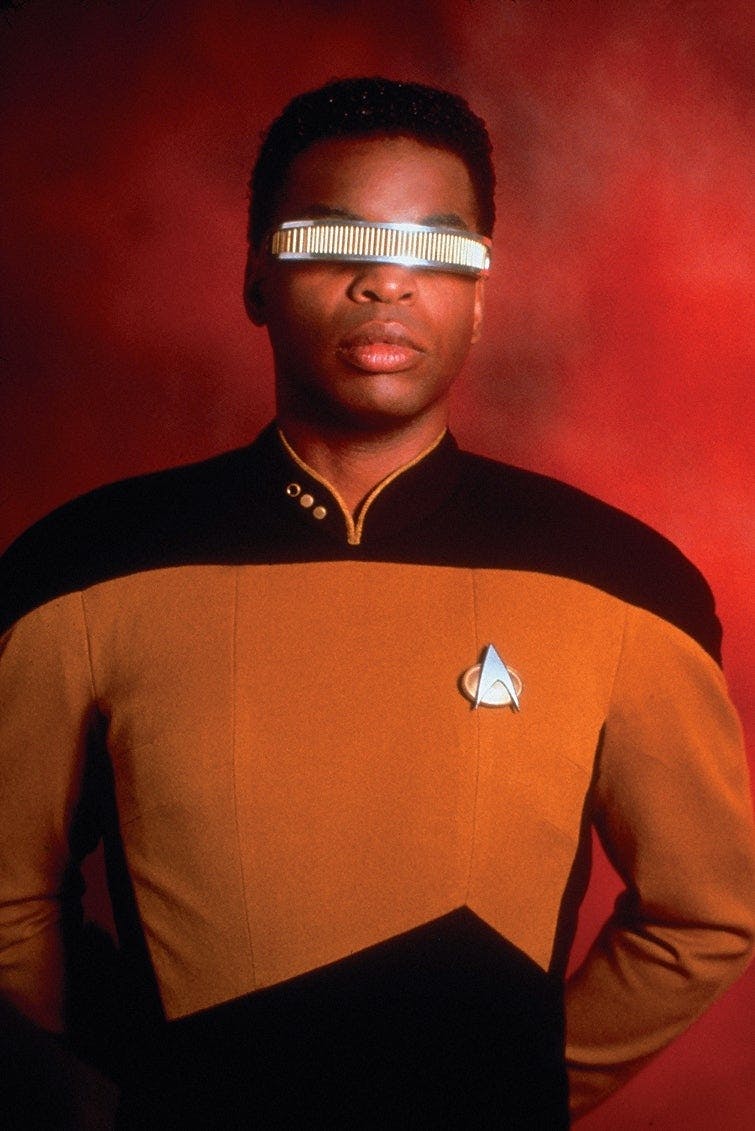

Geordi La Forge’s character is a perfect example of Starfleet embracing the social model of disability. Born blind, he requires an accommodation in the form of a visor to see. Unlike Melora, though, he’s treated as an equal by the crew. Picard doesn’t consult Dr. Crusher about Geordi’s ability to complete his work. The crew doesn’t uphold Geordi as an inspiration because of his disability. They respect him because of his personality and the work that he does. Moreover, his visor often aids missions. He saves the day many times by seeing things the rest of the crew cannot. Our differences are important. Accommodations and respect benefit all.

Seven of Nine is another example of a disabled character being treated as an equal, though her equality is hard-won. Her cyborg body initially causes fear among the Voyager crew, notably by B’Elanna Torres, who eventually comes to respect her. In Seven of Nine’s case, the reaction her body causes has less to do its appearance and more to do with the history of trauma caused by the Borg. She carries that history everywhere she goes. Her cyborg body becomes an essential aspect of her identity. With the xB’s, the new Picard series has another opportunity to explore disability. Will the xB’s be accommodated into the Picard universe? As Melora, Geordi, and Seven of Nine show, accommodations can only improve Starfleet.

Everyone uses technology, gadgets, medicine, design, etc. in some way to accommodate their abilities. While Starfleet has a mixed history of embracing disability, when they do, they show how accommodating and including folk of all abilities, rather than stigmatizing and pitying those deemed “too different” to be normal, can create a better future for all.

Margaret Kingsbury (she/her) is a contributing writer at Book Riot, where she raves about the SFF books she loves. She writes about children's books at Baby Librarians, a website she co-founded, and you can find her on Twitter @areaderlymom and on Instagram @babylibrarians