Published Jul 2, 2012

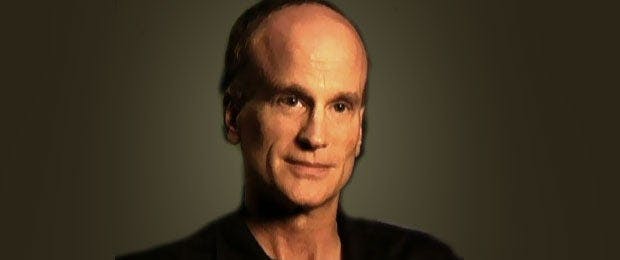

David Livingston On Directing Star Trek Episodes, Part 1

David Livingston On Directing Star Trek Episodes, Part 1

There are prolific Star Trek directors, and then there’s David Livingston. Livingston – who started out on The Next Generation as a unit production manager and worked his way up the ranks to director – called the shots on 62 hours of Star Trek television and directed episodes of all four post-TOS Trek adventures. By the time he shouted “Cut” for the last time, Livingston had helmed two episodes of TNG, 17 episodes of Deep Space Nine, 28 episodes of Voyager and 15 episodes of Enterprise. Along the way, he received story credit for the DS9 hour “The Nagus” and, infamously, it turns out, had a lionfish named after him. Yes, Livingston the lionfish, as seen in Picard’s ready room, is a tip of the cap/a flip of the bird, to the subject of our latest StarTrek.com interview subject.

Over the course of an hour, Livingston spoke candidly about his nearly 20-year tour of duty in the Star Trek universe. Other topics of interest addressed include his upcoming appearance at Creation Entertainment’s Official Star Trek Convention, to be held in Las Vegas next month, and what he’s doing to earn a living these days. Below is part one of our extensive interview, and check back tomorrow for part two.

Put Star Trek in the context of your career for us. Was it your most important job? Was it your favorite? Or was it one job among many and it just happens to be the one people are still interested in hearing about 25 years later?

Livingston: It’s certainly the most important job and also the longest-lasting. I did a lot of jobs on Star Trek. So it wasn’t as if it was just one job, but directing was my favorite of the jobs. I started off as the production manager on “Encounter at Farpoint,” and I was actually going to leave the show at Christmas, around halfway through the first season because I didn’t want to do episodic television. The grind of being a production manager is just not something I ever liked. I did it a lot, but I never liked it.

You actually told them you were leaving, them being Rick Berman and Robert Justman, right?

Livingston: That’s right. Rick and Bob called me in and said that Bob is leaving the show because he just wanted to get it up on its feet, that he’d done what he wanted to do for the show and now was going to go take it easy. Rick said there’s part of Bob’s job open, a line producer kind of job, and they offered me that position as line producer. I didn’t have to be the production manager anymore, which was fine and dandy with me. A lot of times on series, the line producer is also the unit production manager, but they made it clear to me that that was not a requirement. So I said, “OK, you’ve got a deal.” So I was making more money and had less work to do. That’s always a good thing.

You did that for about four years, at which point you noticed several members of the cast and crew throwing their hats into the rings as DITs – directors in training. And, soon enough, it was Berman who asked you if you wanted to direct. Had you always wanted to direct?

Livingston: It was something I’d wanted to do forever. I’d gone to film school and wanted to be a director, but it was something I was always professionally really fearful of. But Rick offered it to me and I said “Sure.” I actually went into therapy to try and deal with my fears and anxieties about doing it. I took classes through the Director’s Guild. I did scene study and talked to the (TNG) editors and other directors. I went to the set to see what other people were doing and sat in with the editors. I went to our DIT school and finally Rick gave me an opportunity to direct.

Your first episode was “The Mind’s Eye.” What went through your mind as you read through the script? And what was the takeaway from having directed that particular show?

I was pushing envelope, even on that episode, which got me into a lot of trouble as a director. But I was running really, really late on the last night of shooting. We were supposed to do a stunt where Picard disarms LeVar, who is the assassin, but it was so late. Patrick (Stewart) and I were talking about it and, finally, convinced myself that all we had to do was just grab the phaser out of LeVar’s hand. That was a huge, huge mistake on my part because it was the finale, and you needed some kind of force, some kind of physical, strong action to cap the episode, especially if you had to have one of your own – Picard or Worf or whoever—attack Geordi to prevent him from killing somebody. I missed that beat. It’s very soft and very unsatisfying, and I always regretted it. But I learned from that.

What did you learn?

Livingston: I said to myself, “I’m never going to do that again. I’m never going to settle. If they fire me, if they pull the plug on me, whatever, I have a responsibility to the script and to the story and to the show as the director not to miss something that important. As I said, I always regretted it, but I made sure in my own mind that I was never going to do that again. And I don’t think I did. As you do more and more episodes, you learn what’s important and what’s not important. So I don’t think I was being obsessive. I learned that you really have to do the beats in the script and you have to deliver it to the audience.

We won’t make you go through every episode of every show, but since you only directed two hours of TNG, what are your thoughts on “Power Play”? That was another possession story…

How in on the ground floor were you when DS9 became a reality?

Livingston: Very. In fact, Rick involved me tremendously in it. I actually went to and participated in the casting sessions for the pilot. During the cast process, Michael Piller said that he wanted to consider having an African American play the commander on the show. They were looking at a lot of black actors. I, as a production manager, had done Uncle Tom’s Cabin with Avery Brooks, and I was a huge fan of his depth as an actor and his seriousness and gravitas, and also his physicality and voice and whole demeanor. I said to Junie Lowry, the casting director, “What about Avery Brooks?” She said, “Oh, that’s a great idea.” A couple of days passed and I didn’t hear anything. I said, “What’s going on with Avery?” She said, “He’s in the Caribbean on vacation, so he’s not reachable.” I said, “Well, come on, he’s reachable. Get a hold of his agent and see if you can send him a script.” She said, “OK, OK, OK.” So, she got back to me again and said, “We were able to get him the material down there on vacation and he read it, and he wants to audition.”

He came out to Los Angeles for it. It was a studio audition. I didn’t go to those, but I remember waiting for him to come out from the audition and saying hi to him. It was kind of cook because I hadn’t seen him prior to that. And he got the job. So, in a way, I feel that I’m partially responsible for Avery being on the show. In fact, Avery has acknowledged that fact to me, and I’m proud of that fact because I really feel that he literally was the soul of that show. Of the four shows, it’s my favorite because, to me, it most reflects what our reality is like. On TNG, everybody was these super-evolved humans. Voyager was sort of the same way. Enterprise, not so much. They were sort of in between. But, DS9 was really a reflection of what we are as a society today. The Ferengi are so human. So, for that season, it was my favorite series.

You have a story credit on “The Nagus.” Take us through how that happened and your thoughts on the episode…

So we’re sitting around talking about the business part of the story. Ira Behr was there. Michael was there. I’m not sure who else was there from the writing staff. But Michael said – and I’ll never forget this – “Well, let’s do The Godfather.” Everybody’s eyes lit up and they all said, “Yeah, of course. Let’s do The Godfather!” Michael pointed to Ira and said, “Ira, you write it,” and Ira wrote it. So, we did The Godfather. When I read that finished script I died and went to heaven. And the only thing I contributed to The Godfather part was the name Zek. That’s it.

Who thought of Wallace Shawn to play Zek? That was just perfect casting…

Livingston: Rick Berman thought of Wally. Rick was brilliant at that. He’d be the best casting director in Hollywood. We were sitting around trying to figure out who to cast. Junie was having a real hard time. Finally, Rick said, “Well, what about Wallace Shawn?” Again, everybody’s eyes lit up. It was a no-brainer. They called and made him an offer, and there’s no one else on the planet who could have played the guy. It was brilliant, perfect casting. And I never had so much fun working with somebody. The irony is that I’d never met Wallace Shawn. I worked with him for eight days and never met him because he was always in the makeup. When you’re an episodic director, you don’t get to participate in the post-production, but I said “I’m going to go to a looping session. I won’t bother anybody.”

Peter Lauritson; that was his domain and I respected that. He respected my domain as production and I respected his domain as post-production. So I didn’t get in the way. I did like to go to some of the music spotting sessions, though, to put in my two cents worth. But I went to the looping session and went up to Wallace. I said, “Hi, Wallace, I’m David. You know me, but I haven’t seen your face in real life. I wanted to say hi now because I’ve only seen you with your goofy makeup on.” That happens. It’s so weird, but when you do Star Trek the people become more real to you with their makeup on than out of makeup because some of these actors, you only saw them on set, in makeup, and they couldn’t take it off during the day. They’d get in at four or five in the morning to put it on and it wouldn’t come off until everyone else has gone home. So, for eight days, all I saw of Wallace Shawn was this weird-looking guy with big ears. It’s a very strange experience.

Visit StarTrek.com again tomorrow for part two of our interview with David Livingston. In it, he talks more about DS9 and discusses directing Voyager and Enterprise, how Picard’s lionfish came to be named Livingston, and his unusual career change.