Published Apr 29, 2022

Celebrate National Poetry Month With Captain Kirk's Favorite Poem

"A tall ship..."

StarTrek.com

Poetry is one of the world’s oldest art forms. It is even believed to predate the written word, existing for centuries as an oral tradition, passed between generations through spoken performances.

According to Star Trek, we can also expect poetry to exist long into the future. Across the franchise, many Trek characters reference and quote poetry from memory. Captain Picard retells The Epic of Gilgamesh, one of Earth’s oldest written poems, in the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode “Darmok.” Captain Janeway keeps the works of Italian poet Dante Alighieri with her onboard the U.S.S. Voyager. Characters as diverse as Khan Noonien Singh and Counselor Troi recite lines from John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost.

StarTrek.com

Many of these poetic references are fleeting – sprinkled in by Trek’s writers to add depth and color to the themes of an individual episode. But, today, in honor of National Poetry Month, we wanted to dig into one of the most significant poetic references in all of Star Trek. It is a reference which occurs several times, giving insight into one of Trek’s most iconic characters and the human condition itself.

This character is, of course, Captain James T. Kirk. While some viewers may think of Kirk as a man of action, he also shows his cultured side several times across the franchise, quoting from a range of literary works. In the Star Trek episode “By Any Other Name” he recites lines from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. And, memorably, he quotes from Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities in the final scene of Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan.

StarTrek.com

But Kirk’s most significant poetic reference comes in the Season Two installment “The Ultimate Computer.” In this episode, the brilliant scientist Doctor Richard Daystrom visits the Enterprise to test a new computer, which could fully automate the ship, enabling it to run without a crew. After Daystrom’s first test performs flawlessly, Kirk is forced into a moment of self-reflection. He tells Doctor McCoy how the test made him feel “useless, unneeded,” to be replaced by “a mass of circuits and relays.” He then asks McCoy “Do you know the one ‘All I ask is a tall ship’?” The Doctor seems to have some familiarity with the quote, replying “It’s a line from a poem, a very old poem, isn’t it?” Kirk affirms this, clarifying that it is from a “20th century Earth” poem.

StarTrek.com

The poem is indeed a 20th century composition, entitled "Sea-Fever." Written by English poet John Masefield in 1903, "Sea-Fever" is a three-verse poem, which expresses a longing for a return to a life of seafaring adventure. The poem was likely inspired by Masefield’s own experiences: he began training for a career in the Navy at the age of just 13, and qualified a few years later, setting sail for Chile and later joining another ship in North America.

Although Kirk’s experience is separated from Masefield’s by over 350 years, and Kirk’s ship sails the stars rather than the seas, he nonetheless feels the same longing as the speaker in "Sea-Fever."

“All I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by,” he repeats to Doctor McCoy, before explaining the personal significance of the poem more fully. “You could feel the wind at your back in those days,” Kirk says, “the sounds of the sea beneath you. And even if you take away the wind and the water, it's still the same. The ship is yours. You can feel her. And the stars are still there”.

StarTrek.com

In this way, Kirk draws a connection between himself and the seafarers of old, like John Masefield. He also sets himself in opposition to the scientist Daystrom.

Daystrom argues that his device means “Men can live and go on to achieve greater things than fact-finding and dying for galactic space”. But while it has practical benefits, Daystrom’s invention overlooks the fact that the Enterprise’s voyage is not merely a “fact-finding” mission. It is also a spiritual journey, which feeds the human thirst for adventure. Or, as Kirk puts it: “There are certain things men must do to remain men.”

StarTrek.com

In this way, Kirk’s poetic reference to "Sea-Fever" highlights the tension that often comes with scientific progress. While it may bring practical benefits to serve the betterment of humankind, it can also risk isolating us from the long-standing needs that are part of our human nature – whether we belong to the age of seafarers or the age of starfarers.

John Masefield, author of the “Sea-Fever” poem, may have felt the same way as Kirk. Born in 1878, he was a product of the Victorian era of wooden sailing ships. But when he died in 1967, scientific progress had pulled the world into a new age of motorized seafaring, trans-Atlantic flight, and burgeoning space travel. As the Irish poet Connor O’Callaghan puts it: “More than any poet I can think of, [Masefield’s] life and work straddle two irreconcilable worlds.”

Kirk also straddles two worlds in "The Ultimate Computer" – the scientific world and the world of human nature. These are physically represented by his diametrically opposed friends, the logical Spock and the emotional Doctor McCoy. So, it is no surprise that when Kirk quotes the “Sea-Fever” poem again many years later in Star Trek V: The Final Frontier it is these two friends who are present.

In this scene, the trio are approaching the Enterprise via shuttlecraft when Kirk spontaneously quotes the line “All I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by.” Despite having been told by Kirk years earlier that it is a 20th century poem, McCoy misidentifies it as a work by the 19th century writer Herman Melville. Spock quickly corrects him, before providing a rare moment of Vulcan humor with the punning explanation “I am well-versed in the classics”.

StarTrek.com

While this scene is a nice call-back to Kirk’s previous reference to “Sea-Fever” in “The Ultimate Computer,” it also has a thematic significance of its own. In this scene, Kirk is approaching the new U.S.S. Enterprise-A for her first mission. In the earlier film Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan we learn that Kirk had left behind the life of a starship Captain. Spock had told him this was a mistake and that “Commanding a starship is your first, best destiny.” Therefore, this scene represents a return to that destiny, as Kirk is finally given command of his own ship again. And by quoting from the “Sea-Fever” poem again, Kirk expresses a fulfillment of that insatiable appetite for adventure that is so much a part of the human spirit, just as much in the 23rd century as it was in Masefield’s day.

This link between the seafaring age and the age of space exploration is physically represented on the ship itself, with a new observation lounge, which includes a ship’s wheel, as well as several other maritime objects. This visual detail also provides a direct reference to “Sea-Fever,” which refers to “the wheel’s kick” in the line following the one Kirk quotes.

StarTrek.com

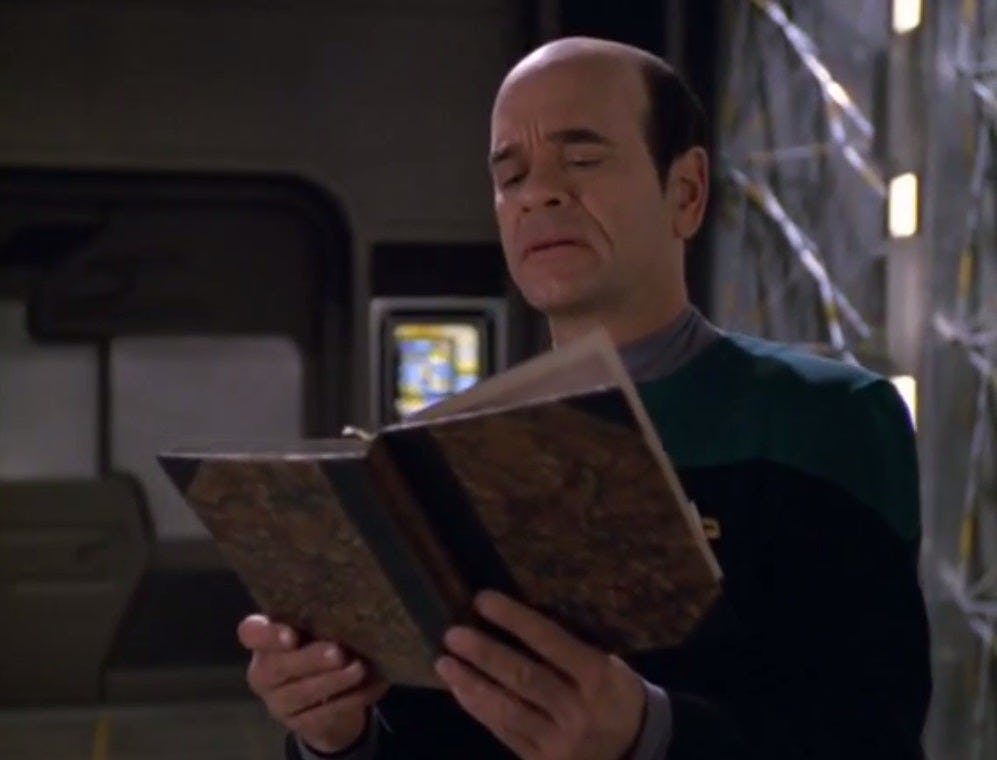

These two direct references to “Sea-Fever” – in “The Ultimate Computer” and in Star Trek V: The Final Frontier – clearly highlight the significance of the poem to Kirk. But, as if this were not enough, the poem is quoted by another character one more time in the franchise. And it is a rather unexpected character.

StarTrek.com

In the Star Trek: Deep Space Nine episode “Little Green Men,” Quark finally gets his own ship, which he modestly christens Quark’s Treasure. Before taking the ship on her maiden voyage, Quark quotes the same line from “Sea-Fever” as Kirk: “All I ask is a tall ship…” However, after a short pause, Quark corrupts the line by concluding “… and a load of contraband to fill it with.”

While this reference is an amusing one, which draws a sharp contrast between Quark and Kirk, it also raises an interesting question. Where did the Ferengi Quark, who has an avowed distaste for human culture, learn of the poem “Sea-Fever?” This question actually has a clear answer, which is visible to eagle-eyed viewers in some episodes of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. And that answer is onboard the U.S.S. Defiant, which includes the line, as originally quoted by Kirk, on its dedication plaque: “All I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by.”

While this explains how Quark may have seen the line and become familiar with it, this detail also has a further thematic resonance for Kirk. It suggests that his own spirit and ideals have become absorbed by Starfleet so fully that they are now “written in stone” onboard the vessels of the organization’s fleet. Despite the threat of Daystrom’s computer, the inclusion of the Masefield quote on the Defiant suggests that Starfleet has found a balance between scientific progress and preservation of the human spirit, rather than merely becoming a “fact-finding” organization.

Overall, by including this reference across several installments of the franchise, Star Trek presents us with the idea that even as humanity progresses technologically into the future, there are some things that will always keep us anchored to the past, through the continuity of our humanity. The spirit of human adventure is one of these things. And poetry is another.

This is what allows the 4,000-year-old Epic of Gilgamesh to remain as compelling to readers today as it ever was. It is what enables Dante’s La Vita Nuova to have as much relevance in 13th century Italy as it does in the 24th century Delta Quadrant. And it is what enables any reader to understand the feeling and longing expressed in John Masefield’s “Sea-Fever,” even if we have never been aboard a sailing ship.

StarTrek.com

National Poetry Month represents a wonderful opportunity to engage with one of humanity’s oldest art forms. By reading poetry, we can learn more about ourselves and others. For Trek fans, John Masefield’s "Sea-Fever" represents a perfect place to start. It is a poem that enables us to look to both the past and the future – articulating that spirit of adventure and exploration common to humans of all eras, and inviting us to consider how it might manifest itself in a far-flung future among the stars.

Christian Kriticos (he/him) is a freelance writer based in London, England. You can find more of his work at www.christiankriticos.com.