Published Apr 7, 2020

Are We Ready for Genetically-Edited Humans?

CRISPR, one of the most innovative technologies, could transform the fields of medicine and agriculture. But will the world’s first gene-edited babies live long and prosper?

StarTrek.com

With “Doctor Bashir, I Presume?,” the fifth season of Deep Space Nine dropped a bombshell when the episode aired back in 1997. It had never occurred to me until that episode how little we knew about Doctor Julian Bashir’s backstory, and the last thing I expected was that he had been genetically-edited as a child. One of my favorite things about Star Trek is its ability to subvert your expectations from the beginning of an episode to the end of one, and this episode was no exception. The idea that Bashir’s stellar Starfleet record and incredible list of accomplishments could be attributed to anything but his own innate abilities had never crossed my mind, and to this day it is one of my favorite twists in a main character’s arc. As Julian laments in the episode, there is “no stigma attached to success.”

StarTrek.com

Over twenty years ago, the idea of a genetically-enhanced human seemed relegated to just the world of science fiction. With the discovery of CRISPR, a specific technology that allows for gene editing, fiction has now become fact. In 1987, Japanese scientists first discovered mysterious repeating sequences in e. Coli’s DNA. As the years passed, researchers discovered even more similar clusters in the DNA of other bacteria. They named the repeating sequences Clustered Repeating Interspaced Palindromic Repeats, or CRISPR for short.

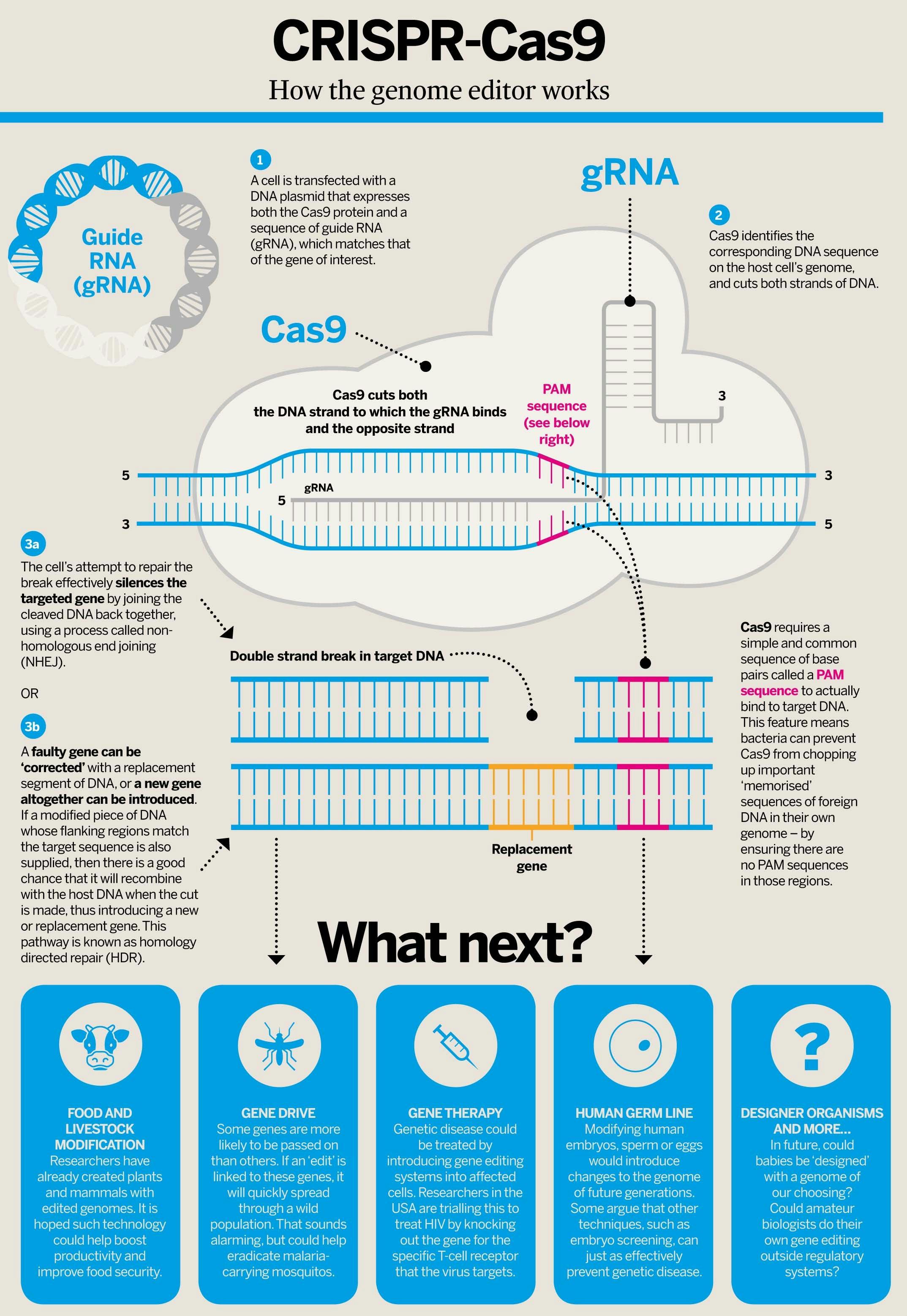

How exactly does CRISPR work? Bacteria are constantly assaulted by viral infections, causing them to create enzymes to destroy the viruses. Once those enzymes are able to destroy the virus, other smaller enzymes come in and clean up the remaining virus’s genetic code and cut it into tiny pieces. Those enzymes then store the fragments in the CRISPR spaces. When future attacks emerge, the bacteria utilize the genetic information stored in those fragments to destroy the virus. Special attack enzymes called Cas9 carry around the stored genetic information to match to a virus’s ribonucleic acid (RNA), thereby chopping up the virus if it matches information stored in the enzyme.

In 2012, research emerged showing that those Cas9 enzymes could be fooled with artificial RNA to seek out anything that matched the same code, not just viruses. Just a year later, scientists demonstrated that CRISPR could be used to edit human cells. What makes CRISPR different from other gene editing techniques is that it’s incredibly precise, easy, and cost-effective. The edits occur in the span of a few days, not weeks or months. Over the past few years, the pace of research surrounding CRISPR has exploded, with refinements for precision and new techniques for manipulating genes emerging at an astounding pace.

The usefulness for CRISPR in a variety of fields cannot be understated. A 2016 paper published in Nature Biotechnology note just a few of the applications for CRISPR: stopping genetic diseases such as BRCA and HIV, editing crops to create more nutritious plants, editing crops to make them disease-resistant, creating more effective antibiotics and antiviral medications, altering entire species, and creating “designer babies.”

StarTrek.com

The concept of designer babies may have once seemed far-fetched, but it is now a reality. In 2018, Chinese scientist He Jiankui revealed that two gene-edited babies had already been born, much to the world’s surprise. While the announcement itself was shocking, the method in which he delivered the information may have been even more so. Jiankui decided to release the information via a YouTube video, with no scientific paper to support his claims, stating that two baby girls—“Lulu” and “Nana”—born via IVF had been edited in an effort to make them resistant to HIV. Jiankui and his colleagues had recruited a man who was HIV positive and a woman who was not to create the embryos. His technique attempted to completely cripple CCR5, which is the gene for a protein on immune cells that HIV utilizes to attack and infect healthy cells. A particular variant of CCR5 that naturally occurs in some of the human population results in a high level of resistance to HIV infection.

Outrage was swift from the scientific community, condemning Jiankui for dangerous and unethical behavior. Many scientists believe that it is far too early to start editing the DNA of human sperm, eggs, or embryos. The procedure performed by Jiankui and his staff may have a whole host of unintended consequences on the twin girls, given both babies are now likely a mosaic of edited and unedited cells. In fact, a study published in Nature Medicine found that the changes made increases the girls’ risk for infectious diseases. China has also now confirmed that a third baby has been born that has undergone the CRISPR procedure.

He Jiankui has since been sentenced to three years in prison for conducting an illegal medical practice; the government concluded that Jiankui had violated Chinese regulations and ethical principles and that regulatory paperwork had been falsified. The Southern University of Science and Technology maintains that it was unaware of Jiankui’s work, and it’s also not clear how much the parents knew about the procedure beforehand. Given the stigma in China surrounding HIV and the lack of access to fertility treatments, the parents likely felt pressure to participate in the study without knowing all the risks.

There is no question that discoveries surrounding CRISPR are astounding, and the potential benefits for disease-resistance and immunity may be limitless. However, there are a variety of ethical and moral implications to consider for genetically-edited humans. The girls may have a higher mortality rate than they would have had otherwise. A recent study prompted MIT Technology Review to suggest that the babies may have increased learning abilities and enhanced memories; however, research surrounding CCR5’s role in memory and cognition is still shaky and not comprehensive. There is simply not enough information to determine whether manipulation of genes can change or improve cognitive function.

Additionally, one must consider the profound psychological impact genetic enhancement may have on a person. In “Doctor Bashir, I Presume?” Julian refers to himself as “unnatural,” a “freak”, a “monster,” and a “fraud.” He views himself as fundamentally flawed and a failure, needing to be modified to be deemed worthy of society, even going as far as to change his name from “Jules” to “Julian.” His anger with his parents that they never even gave him a chance to move past his learning difficulties as a child is certainly valid, as he believed that they simply viewed him as a disappointment.

StarTrek.com

One of the most powerful moments of the episode is the speech made by Julian’s mother. Her pain when acknowledging how difficult it is to watch your child fall further and further behind each day is palpable (this scene is made even more impressive when you know that Fadwa El Guindi is not a professional actress but an anthropologist, and to this day this episode remains her only acting credit). It’s easy for people to pontificate about the perils and pitfalls of something like gene editing, but when it’s your child that could benefit from the procedure, the line between what is right and wrong gets a bit blurry. No parent wants to sit idly by while your child struggles and fails when they know there is something that can be done to help them. As Julian’s father passionately argued, he feels that Julian was saved from a life of remedial education and no opportunities. His parents know what they did was against the law, but their actions in turn gave Julian a far better chance at life than he likely would have had otherwise.

We are still years away from more research on the physical and mental effects of genetic editing on humans, and for now, caution does seem to be the best course of action when it comes to utilizing CRISPR on humans. However, the benefits of immunizing humans from debilitating diseases and enhancing cognition may well outweigh the negatives, and it appears that CRISPR is here to stay. Recently, scientists used the technique on a patient by injecting the tool into the eye of a patient with a rare genetic disorder in an attempt to cure blindness.

Aiming to improve the human population is a noble goal, but at what cost? And what, in fact, makes a person human? As Chief Miles O’Brien notes, genetic editing cannot give you a personality, ambition, or compassion. Eugenics is a very slippery slope, however, and these practices are inextricably connected to racist, sexist, and ableist beliefs. And while we have not yet created “superhumans” with a lust for world domination, the warnings from DS9 and Julian Bashir’s story seem even more prescient today.

Nicole Zub (she/her) is a lifelong Star Trek fan and freelance writer based in Kentucky. She is always dreaming about a place far beyond the stars. You can find her on Twitter @zubmarine4.