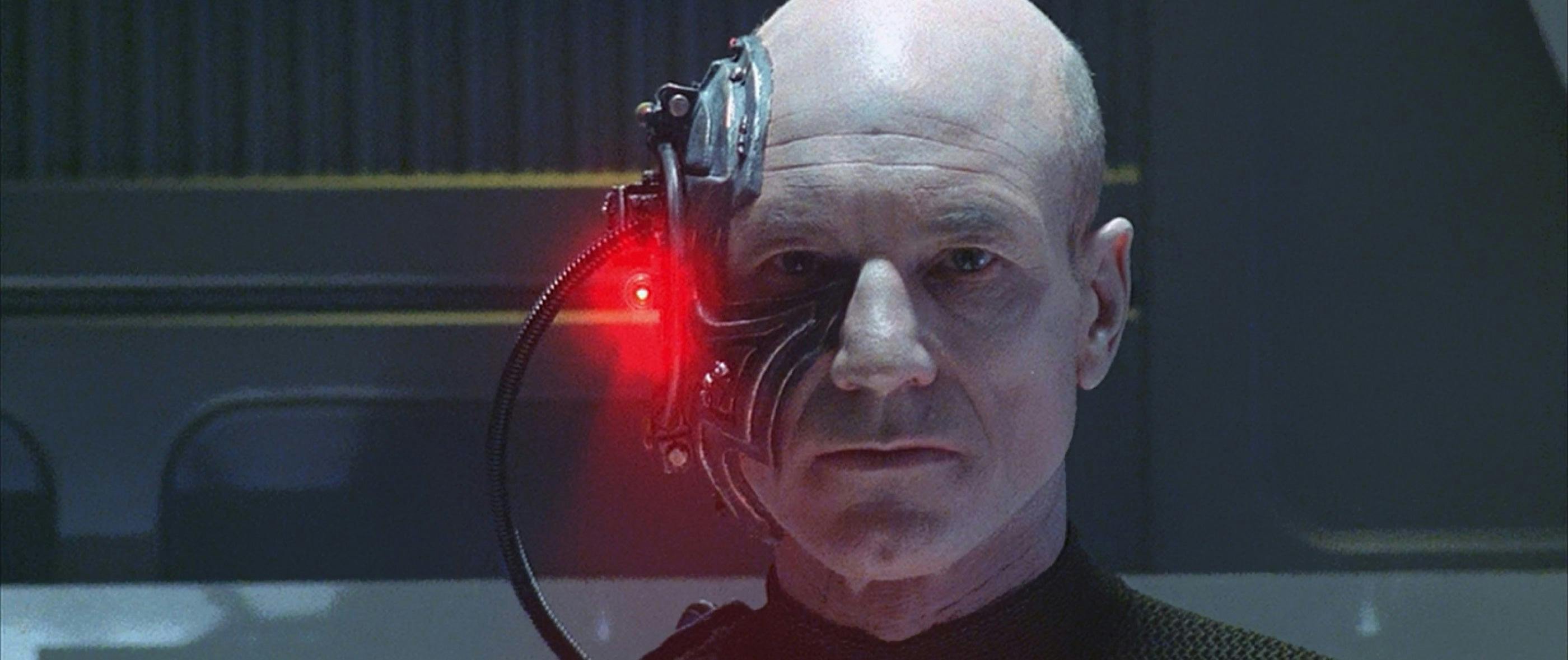

“I am Locutus, of Borg. Resistance... is futile. Your life as it has been is over.” Spoken by Captain Picard on the season-three finale of Star Trek: Next Generation, this has to be one of the most-chilling bits of dialogue in the entire Star Trek canon. It’s not just Patrick Stewart’s cold-blooded delivery, but also the image that accompanies it. Picard has been modified. His head has been augmented with Borg technology, a cortical processor has been implanted in his brain and a laser scope is mounted below his right eye. A cable circulating hydraulic nano-fluids runs from his motorized right arm into his skull.

We are deeply fascinated and unsettled by this man who is no longer wholly human. Like Frankenstein’s monster Picard has been remade in a laboratory, his body hacked, drilled and resectioned. It’s fuel for our nightmares. Yet we live in a world where medical technology and freedom of aesthetic choice make implants and body modification possible, even commonplace.

When we can have acrylic rings inserted into our corneas to correct nearsightedness, defibrillators embedded in our chests to shock an arresting heart, and sacks of silicone implanted in our buttocks to create Kim Kardashian curves, why does Locutus disquiet us?

Aren’t we, like him, Borg?

Last week, I spent three hours in a dental chair while an oral surgeon implanted a titanium rod in my jaw. It’s a screw-like post that forms the base of a dental implant. I was so taken with the X-ray I asked the surgeon to email me a copy. Here in black and white is proof I am now a cyborg. Part human, part mechanical device. What you can’t see on the X-ray is the xenotransplant. Living tissue from a non-human species (bovine bone) has been packed around the implant where, over time, it will be integrated into my natural bone.

Assimilating a foreign species, technology embedded in my jaw: Am I Borg?

It’s estimated that as many as five million Americans are implanted with medical devices each year. The most-popular procedure is almost exclusively performed on children: a myringotomy where a polymer tube is inserted into the eardrum to prevent buildup of fluid in the inner ear. Nearly a million kids a year have this done. Yet we recoil when we see a Borg maturation chamber (Star Trek: Voyager) containing an infant augmented with cochlear implants.

Why? What’s the difference between our implant technology and the Borg’s? Is augmenting our bodies only acceptable when there is a medical need, such as a recurring ear infection or heart arrhythmia? What about procedures we elect to undergo for aesthetics? Breast augmentation, chin augmentation, silicone six packs? Over 300,000 Americans underwent breast augmentations in 2017. Clearly, there is widespread acceptance and adoption of body modification for both medical and aesthetic reasons.

Could the difference be then that we consider it immoral to remove healthy organs and limbs and replace them with performance-enhancing technology? When we believe the Borg have removed Picard’s right arm and replaced it with a prosthetic equipped with a multi-functional tool, we are repulsed. This represents mutilation to us… but does it also represent our future?

DARPA is currently developing wearable mobile machines called exoskeletons which increase the strength and endurance of troops in battle. Elon Musk’s company Neuralink is creating a BMI (brain-machine interface) which can be implanted into the human brain to augment intelligence and create a “neural lace” network. Google has filed patent on a lens implant that requires drilling a hole through the eye’s natural lens in a procedure eerily similar to the one performed on Picard by the Borg in Star Trek: First Contact. When big companies put big money into mashups of healthy human tissue and high tech you can bet we haven’t heard the last of it.

The drive to integrate our biology with our technology is part of a movement called transhumanism. Transhumanists believe in pushing human capabilities beyond their natural limits. Superior bodies, superior minds and immortality are the ultimate goals.

Borg are the living definition of transhuman. Their augmented bodies give them incredible physical strength. Their neural processors and collective “hive mind” give them a computational power beyond our understanding. And immortality? In Star Trek: Voyager, Seven of Nine, a former Borg, tells us, “When a drone is damaged beyond repair, it is discarded. But its memories continue to exist in the collective consciousness. To use a human term, the Borg are immortal.”

Is this why we feel both horror and fascination when we first see Locutus on the Borg cube? Do we recognize the Borg as an allegory for our future selves? If we continue to embrace technology and push the boundaries of what it means to be human will we evolve into drones who use their technology for one purpose: to acquire more technology?

Maybe.

The Borg, in their singular pursuit of technology, have lost appreciation for human beauty. Their bodies are enhanced solely for function. Could this be the real reason they repel us? Utilitarian black hoses plugged into necks, a scrapper’s yard of body hacks, hands a virtual toolbox of pincers and cogs? Neither slick nor pretty, the Borg are the embodiment of anti-aesthetic… which just might be the most alien thing about them. After all, haven’t we always hoped the future would be beautiful?

To learn more about this subject, please visit www.LearningForASmallWorld.com. The course "Star Trek: Inspiring Culture and Technology” provides greater depth on this and many more aspects of the history and impact of Star Trek.

J.V. Jones is a USA Today bestselling writer whose acclaimed Sword of Shadows series is published by Tor Books.