Published Sep 22, 2016

50 Years Later: Where No Man Has Gone Before

50 Years Later: Where No Man Has Gone Before

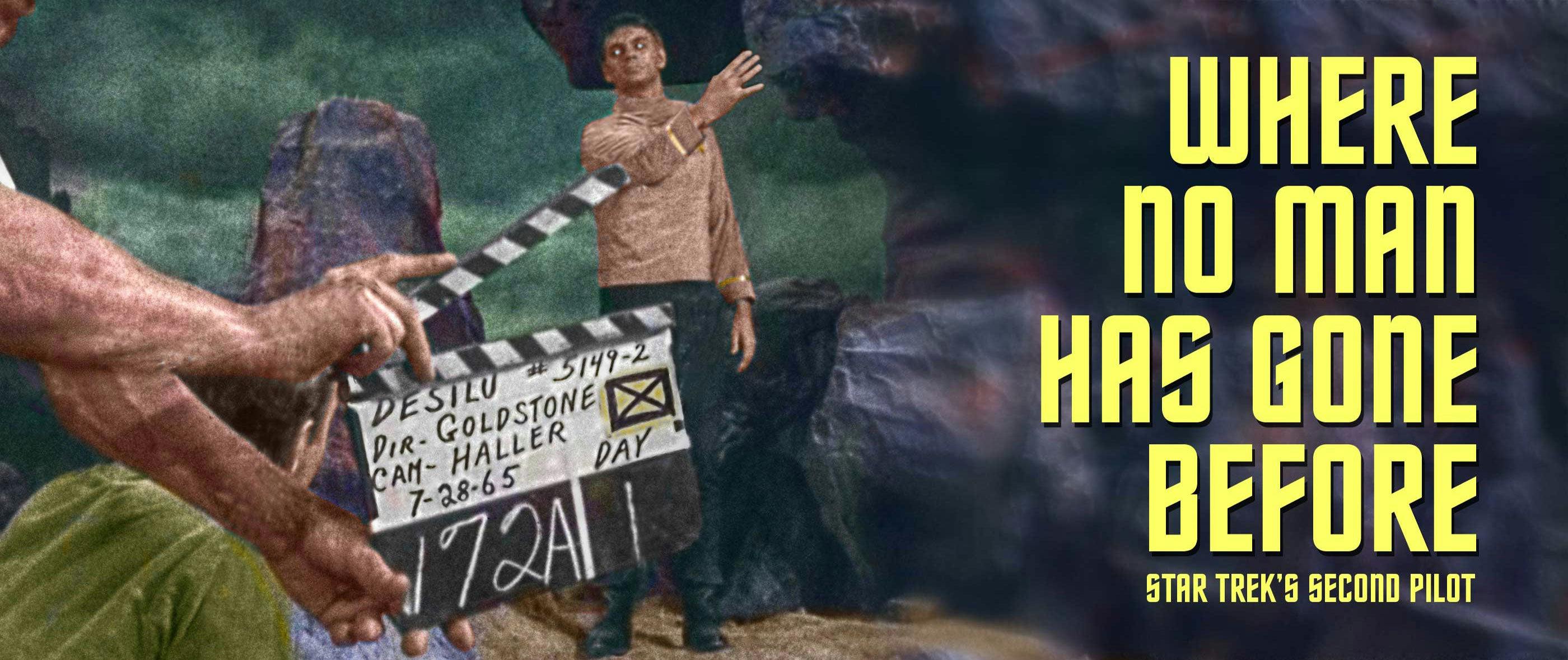

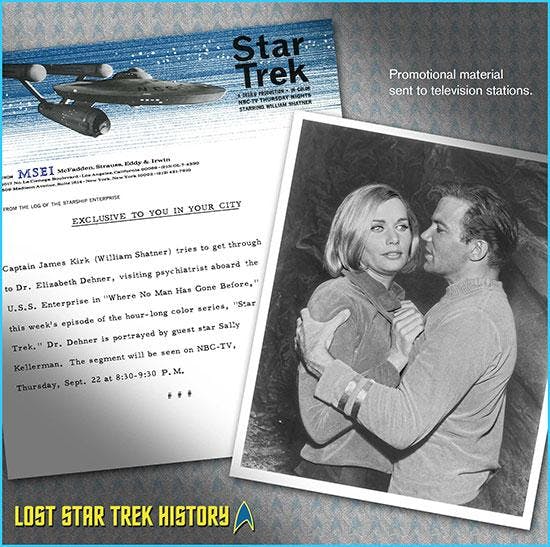

“Where No Man Has Gone Before” was the second pilot made for Star Trek, and it came about because “The Cage,” the first pilot, failed to sell the series to the NBC network. As we mentioned in last month’s article, the executives at the network realized after viewing “The Cage” that Gene Roddenberry and Desilu Studios could produce mature science fiction, but that the story they told in that first adventure wasn’t what NBC was looking for. Thus, the network took an unusual step and requested another pilot for the series. This time, however, they made it clear to Roddenberry that they wanted a simpler, less erotic action-adventure story and a somewhat different cast.

So, with those marching orders, Roddenberry went to work retooling Star Trek. He fleshed out not only his ideas for a new story concept, but he also invited other writers to pitch theirs. Finally, out of three possibilities (“Where No Man Has Gone Before” by Samuel A. Peeples, “Mudd’s Women” by Stephen Kandel and “The Omega Glory” by Gene Roddenberry), “Where No Man Has Gone Before” was selected by the network to put into production. This story was on the mark, as far as NBC was concerned, because it gave them almost everything they asked for. And, after the network viewed the finished film, they were sold… and so was Star Trek. The Original Series was officially green lit, and that started its historic trek to television.

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the television premiere of “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” we thought we’d explore the galactic barrier and present two behind-the-scenes snippets about it.

Mr. Mitchell, we’re leaving the galaxy. Ahead, warp factor one.

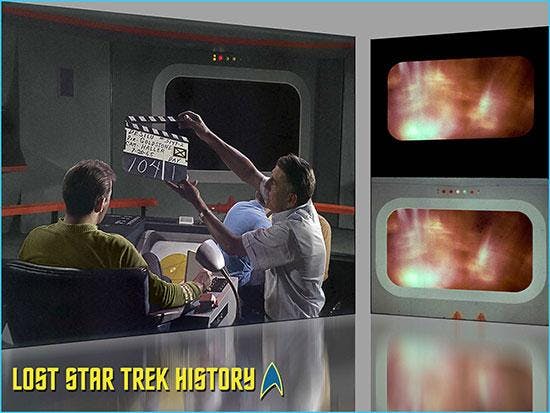

Most of the viewing displays in “The Cage” – for example the one in the briefing room and the monitors above the bridge stations – were frosted screens that had slides and motion pictures rear projected onto them. Although this approach was tedious and noisy (and expensive, as they had to pay the projector operators), rear projection allowed the actors to see and react in real time to what was displayed. This wasn’t the case, however, for the viewing screens in “Where No Man Has Gone Before” and the rest of the episodes, more or less. For the most part, the active graphics on the viewing screens from the second pilot onwards were separate optical elements that were inserted into them in post-production. This meant, of course, that the actors had to use their craft to imagine what they were not seeing.

As an example of the optical effects work that was used to insert images on the main viewing screen (MVS), here’s a photo sequence from “Where No Man Has Gone Before” that shows how the galactic barrier was placed on it.

The large photo on the left in the above collage is from a frame of film showing William Shatner watching the MVS as the scene is slated by John Eckert. The black area in the interior of the screen is the “hole” that’s been added to it in post-production and will be the place where the footage of the barrier display will be added. The upper photo on the right shows a frame from galactic barrier footage that will be inserted into the MVS. According to the script, the galactic barrier was to resemble an aurora borealis, so it was created, in part, by flooding a brightly-lit cloud tank with colored ink/paint and photographing the results. Using the optical printer, the completed footage of the barrier was then matted (masked) to the size of the MVS. Finally, the matted galactic barrier film was rephotographed together with the footage of the MVS with the “hole” in it to complete the effect as shown in the bottom right photo.Rejected Barrier Effects

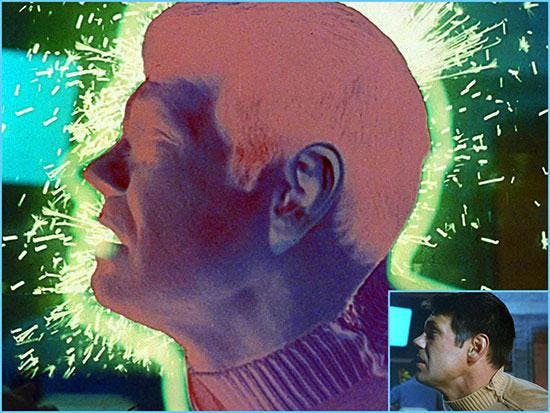

When the Enterprise encountered the galactic barrier in the first act, it wreaked havoc on the ship and its crew. On the bridge, we saw electronic panels exploding and Elizabeth Dehner and Gary Mitchell (Gary Lockwood) turning negative as they got shocked with thick, sparking lines. (An example of this latter effect, done in post-production via mattes and animation techniques, is shown below.)

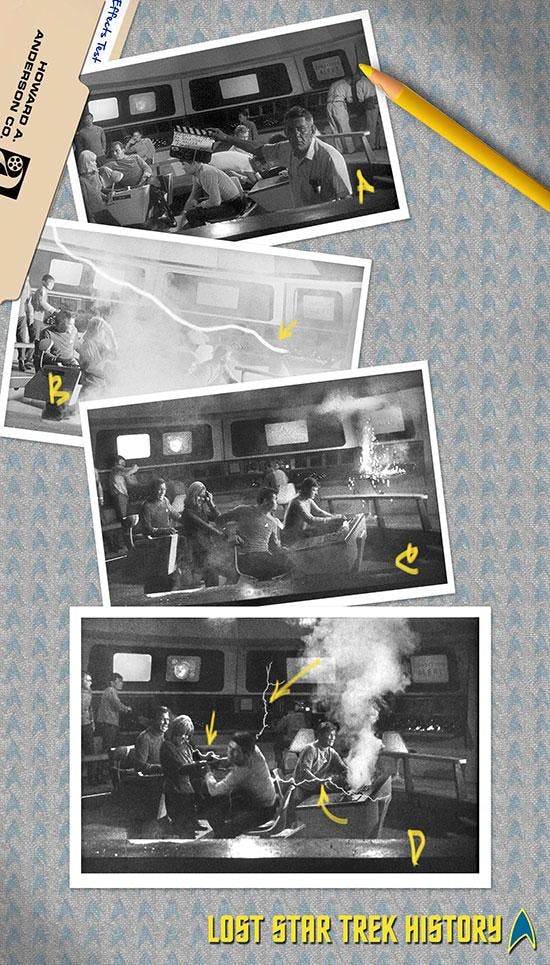

Interestingly, though, this entire sequence originally had different effects that, for unknown reasons, were left on the cutting room floor. Presented below are photos from frames of black and white daily footage that show them, and please note that the captions for the letters in the bottom corners of the pictures can be found after the collage.

Photo A: This first frame comes from before the scene began and shows the cast relaxing before the action started. The technicians in front of the navigation console and on the far right are preparing flash pots (containers holding special pyrotechnic powder) for the soon-to-be-happening explosion and related shower effects.

Photo B: After the director called for action, the bridge was filled with smoke to create the illusion of off-stage fire and a scissor arc lamp was fired to simulate the flash of light for the static electric “lightning bolt” from the barrier. Of course, the lightning bolt striking the bridge panel (denoted by the yellow arrow) was added in post-production and was not seen in the completed and broadcast episode.

Photo C: After being zapped by the barrier lightening, the bridge panel then erupted in a shower of sparks courtesy of a flash pot.

Photo D: Later in this scene, the flash pot on the navigation console was ignited and, simultaneously, Gary Mitchell got hit with several bolts of static electricity that amplified his “Esper” ability (courtesy of optical effects and denoted by the yellow arrows). It’s interesting that the animation effects in this discarded sequence are different from those used in the finished episode (shown earlier) but similar to the ones that were later used in sickbay when Mitchell attacked Kirk and Spock.

And with that, we’ve ordered Mr. Kelso to get us out of here. Lateral power!

Biographical Information

David Tilotta is a professor at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, NC and works in the areas of chemistry and sustainable materials technology. You can email David at david.tilotta@frontier.com. Curt McAloney is an accomplished graphic artist with extensive experience in multimedia, Internet and print design. He resides in a suburb of the Twin Cities in Minnesota, and can be contacted at curt@curtsmedia.com. Together, Curt and David work on startrekhistory.com. Their Star Trek work has appeared in the Star Trek Magazine and Star Trek: The Original Series 365 by Paula M. Block with Terry J. Erdmann.