StarTrek.com | Shutterstock/Everett Historical

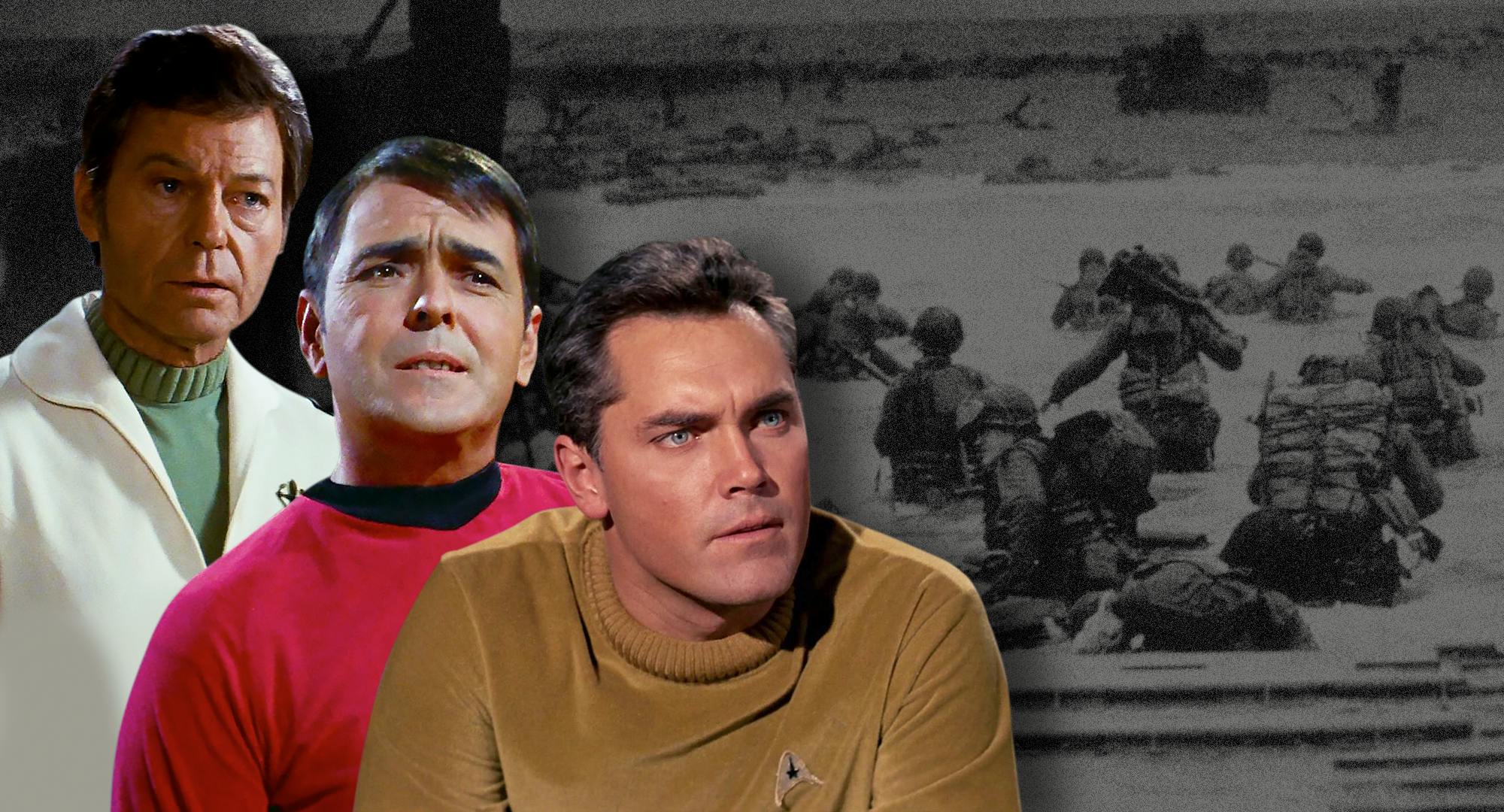

If ever an officer on the original Enterprise required dextrous fingers it was Scotty, whose delicate handling of the transporter’s iconic sliding buttons ensured that anyone beaming up to the ship arrived with their atoms intact. But ironically James Doohan, who played the miracle-working engineer, was forced to rely on a hand double since he was lacking the full ten digits. Eagle-eyed viewers would have spotted, in less carefully composed wide shots, that Doohan was missing the middle finger on his right hand – the legacy of a war wound sustained on D-Day. June 6, 1944 was an eventful day for the young Lieutenant Doohan, but by the time darkness fell, he believed the worst to have passed. So it came as a shock when, walking back to his command post a little before midnight, he found himself under machine-gun fire. One bullet was stopped by a cigarette case in his breast pocket – the only time, he later joked, that being a smoker had improved his health – four more struck him in the leg, and several shot his finger to pieces. Somehow, Doohan made it to the nearest first aid post, where they bandaged up his bloody hand, before sending him to a hospital back in England. The finger was amputated at the middle knuckle, but the stump had limited movement, so Doohan – on his doctor’s advice – chose to have it taken off altogether. It was either that, he mused, “or spend my life looking as though I was flipping someone an obscene gesture.”Doohan’s D-Day story is certainly a dramatic one, but he was far from the only World War II veteran working on Star Trek, whether in front of the camera or behind it. When the show tackled themes connected to the war – in “Patterns of Force” or “The City on the Edge of Forever,” for example – it was not imagined versions of history being invoked, but the creators’ own lived experiences. The ‘two Genes’ at the helm, Roddenberry and Coon, had both been stationed in the Pacific, while Matt Jefferies’ service had taken him as far as North Africa. Bob Justman had served as a Radioman in the US Navy, and DeForest Kelley had operated a control tower at an Army Airbase in New Mexico. Even those who had been too young to serve, such as William Shatner and Leonard Nimoy (both born into immigrant Jewish families) had grown up under the shadow of the war years, and their memories of that terrifying time were still fresh. Here, then, in commemoration of the 76th anniversary of the D-Day landings, are some of the war stories of the people who made Star Trek.

James Doohan

StarTrek.com

Jimmy Doohan signed up for the Royal Canadian Artillery at the age of 19 and shipped out to England soon after his twentieth birthday. There followed more than four years of waiting before he would see any real action. He spent most of the time, as he later recalled, "going to pubs, eating fish and chips, and drinking warm British beer." But he also completed the officer’s training course, receiving his commission as a lieutenant, and – perhaps more significantly – met a man who would prove a major influence on his career: a fellow soldier from Aberdeen by the name of Andrew. Doohan had always been good with accents and soon mastered his comrade’s Scottish brogue, filing it away for the future. (He later claimed to have softened the accent on the advice of Gene Roddenberry, who told him that if he reproduced it too accurately, no-one would have a clue what Scotty was saying.)And then, at long last, the preparations for a second front began. Doohan and his men trained for six weeks with the Royal Navy, rehearsing for an ambitious amphibious landing on the coast of France. On D-Day itself, Doohan was in charge of 120 men from the Winnipeg Rifles, part of the 21,000-strong Anglo-Canadian force charged with capturing Juno Beach. After many hours at sea, during which he accumulated a small fortune in craps winnings, the order was given to make landfall. Doohan bundled into an Assault Landing Craft along with 33 other men, and finally they bumped up against the beach. It was, he wrote in his memoirs, “a cacophony of violence.” The noise of the explosions and gunfire was deafening, and the air was baking hot from the shells constantly bursting overhead. Somehow Doohan and his 33 men made it to the cover of the sand dunes without anyone being hit, before scrambling onto a road leading inland. Fortunately, thanks to the incident with the missing finger, Doohan’s time on the frontline was brief. By the morning of D-Day Plus One, he was in a hospital bed back in England. Once recovered from his injuries, he was sent to flying school with the Royal Canadian Air Force, where he proved to be something of a daredevil, slaloming between telegraph poles in a Taylorcraft Auster Mark IV aircraft. The incident was not exactly popular with the top brass, but it soon earned him a reputation among the men as the “craziest pilot in the Canadian Air Force.”

DeForest Kelley

StarTrek.com

When DeForest Kelley was called up on March 3, 1943 it couldn’t have come at a worse moment. Only the day before, the aspiring actor had learned that Hollywood maverick Walter Wanger wanted to sign him on a fixed-term agreement. Now he would have to serve out a much more arduous contract instead.

Kelley’s performing background did, however, help him towards a fairly cushy posting. With basic training complete, he was assigned to Signals in the Army Air Corps, dividing his time between stints as a public relations writer and – thanks to his previous radio experience – a control tower operator at an Air Base in Roswell, New Mexico.Work in the control tower might have been safe, but it still had its hair-raising moments. On one occasion, Kelley was left shaken when two aircraft began approaching the same landing strip, ignoring his increasingly frantic entreaties to "Pull up!" Whether the flyboys were deliberately teasing him with their daredevil antics he was never quite sure, but the thought of the horrific accident that might have ensued on his watch continued to haunt him. Eventually, the Army took Kelley all the way to Hollywood. In January 1945, he was transferred to Hal Roach Studios, where he worked as a production technician for the First Motion Picture Unit. He even found his way in front of the camera, appearing in a pair of instructional videos: “How to Clean Your Gun” and “How to Act if Captured." By the time he was demobbed in 1946, he had signed a one-year contract with Paramount.

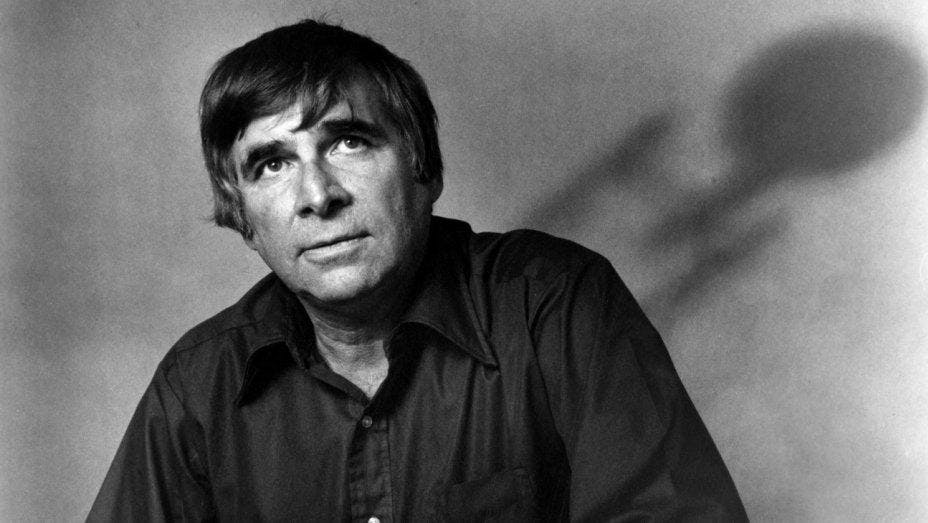

Gene Roddenberry

StarTrek.com

The Great Bird of the Galaxy was formerly a US Army pilot. Gene Roddenberry joined the civilian pilot training program at the age of eighteen, before enlisting in the Army Air Corps. Within days of the attack on Pearl Harbor, he received his call-up papers, and eight months later he was commissioned as a second lieutenant. Thanks to his height, Roddenberry was considered unsuitable for fighter service, so he was assigned to fly B-17 bombers instead, operating out of Hawaii. To begin with he was mostly on reconnaissance, sometimes clocking up to eleven hours in the air, but the lengthy flights were not entirely without incident. On one occasion, Roddenberry and his crew were lucky to survive after he successfully piloted them directly through a typhoon. In January 1943, Roddenberry began flying actual bombing missions. One of his most frequent targets was an airport on the island of Bougainville, which was under Japanese occupation. The raids would take place at dusk, utilizing half a dozen B-17s, with no fighter escort. During one incident, Roddenberry’s plane came under attack from several Japanese fighters. He sought sanctuary in a bank of clouds, allowing his navigator to shoot down the enemy aircraft, and made it back to base in one piece.Roddenberry estimated that he flew around ninety missions in total. He had his fair share of scrapes, but the most serious incident involved no enemy forces at all. He was piloting one of the new B-24 bombers from a base in Guadalcanal, when he was forced to abort an unsuccessful take-off. Unfortunately, the plane’s brakes failed and it ploughed on past the end of the runway before crashing into a clump of palm trees and bursting into flames. Roddenberry and most of his crew evacuated, but the navigator and bombardier in the nose of the plane lost their lives. A formal enquiry cleared Roddenberry of any wrongdoing, but some of the other men were less forgiving. Before long, he found himself reassigned to Los Angeles, where he spent the rest of the war as an Army air crash investigator.Roddenberry was demobbed in 1945, having earned the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal. He hadn’t made many close friends during his war service, but there was one man he was determined to reconnect with: a Chinese pilot called Kim Noonien Singh, who he had befriended during his time in Hawaii. Unable to track the other man down, despite his unusual name, Roddenberry tried twice to get his attention in the best way he knew how – by naming a Star Trek character after him. Sadly, though, neither the appearance of Khan Noonien Singh in 1967, nor Data’s creator Noonian Soong two decades later, succeeded in putting the two of them back in contact.

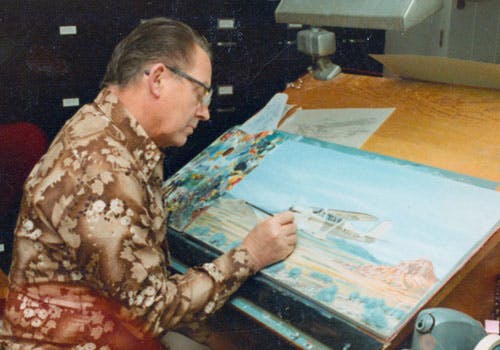

Matt Jefferies

mattjefferies.com

The man who designed the original Enterprise cut his teeth on some very different flying machines. Having requested a transfer from the infantry to the Army Air Corps in 1941, the twenty-year-old Matt Jefferies was thrilled to qualify as a flight engineer on the B-17 bomber. Leaving the United States in August the following year, Jefferies arrived in Swansea, Wales, and was assigned to an airbase in Poddington, a former RAF command station in Bedfordshire. Four months later, Jefferies and his comrades boarded a steamship for Algeria, where he would see frontline service as a co-pilot in the North African campaign. Now flying in a B-25 bomber, he was lucky to survive his mandatory 25 service missions, and was awarded the Air Medal and the Bronze Star for his service. Like any wartime pilot, Jefferies suffered a few close shaves. In July 1943, while he was stationed at a base in Tunis, his B-25 crash-landed due to faulty nose gear. Jefferies sustained lacerations to his face and broke his front teeth when he was thrown into the control yoke. Tending to his injuries, the flight surgeon was surprised to hear Jefferies describe the crash as “a good landing.” “What’s good about a crash landing?” he asked him. Jeffries attempted a painful smile as he replied, “Any landing you can walk away from is a good landing.”

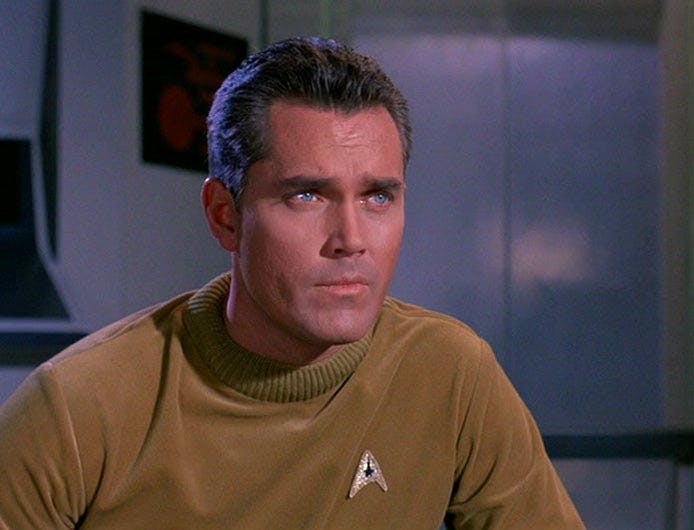

Jeffrey Hunter

StarTrek.com

The original captain of the Enterprise came to Starfleet having served his time in the US Navy. Jeffrey Hunter graduated from high school in June 1944, around the time of the D-Day landings, and completed a naval radar course at the Radio Technical School. In May 1945, just as the war in Europe was drawing to an end, he was made Seaman First Class and assigned to the Headquarters of the Ninth Naval District at Great Lakes, Illinois. He never saw combat duty, thanks in part to a foot injury sustained in a high-school football match, but he spent a year working on the teletype exchange at Great Lakes, before being discharged in 1946. Hunter went on to university to study Speech and Radio at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, alongside a number of fellow former servicemen who were broadening their horizons thanks to the GI Bill.

Gene Coon

Memory Alpha

The ‘other Gene’ responsible for Star Trek’s early success, Coon enlisted as a Marine in August 1942. Initially stationed in the United States, he was later posted to Japan as part of the Allied Occupation forces, and then to China, where he began editing and publishing a small newspaper. He was discharged in 1946 but his service record didn’t end there. In 1948 he signed up for the Marine Corps Reserves, and in 1950 he was called back to active duty, going on to spend two years in Korea as a Marine Radio correspondent.

Fred Freiberger

Memory Alpha

A New York native, the third-season Star Trek producer had been working in advertising when war broke out, but soon found himself swapping Madison Avenue for military service. He trained as a navigator and was stationed in England with the United States Eighth Air Force, but was shot down over Germany in an incident which earned him a Purple Heart. He spent the next twenty-two months out of action in a prisoner-of-war camp, before being liberated in 1945.

Further Reading:

David Alexander, Star Trek Creator: The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry

James Doohan (with Peter David), Beam Me Up, Scotty: Star Trek’s “Scotty” in His Own Words

Richard L. Jefferies, Beyond the Clouds: The Lifetime Trek of Walter "Matt" Jefferies

Terry Le Rioux, From Sawdust to Stardust: The Biography of DeForest Kelley

Duncan Barrett (@BarrettsBooks) is the co-author of Star Trek: The Human Frontier and the host of ‘Primitive Culture’, a TrekFM podcast about Star Trek and history.