Published Nov 1, 2023

10 Ways Mary Shelley's Influence Lives On in Star Trek

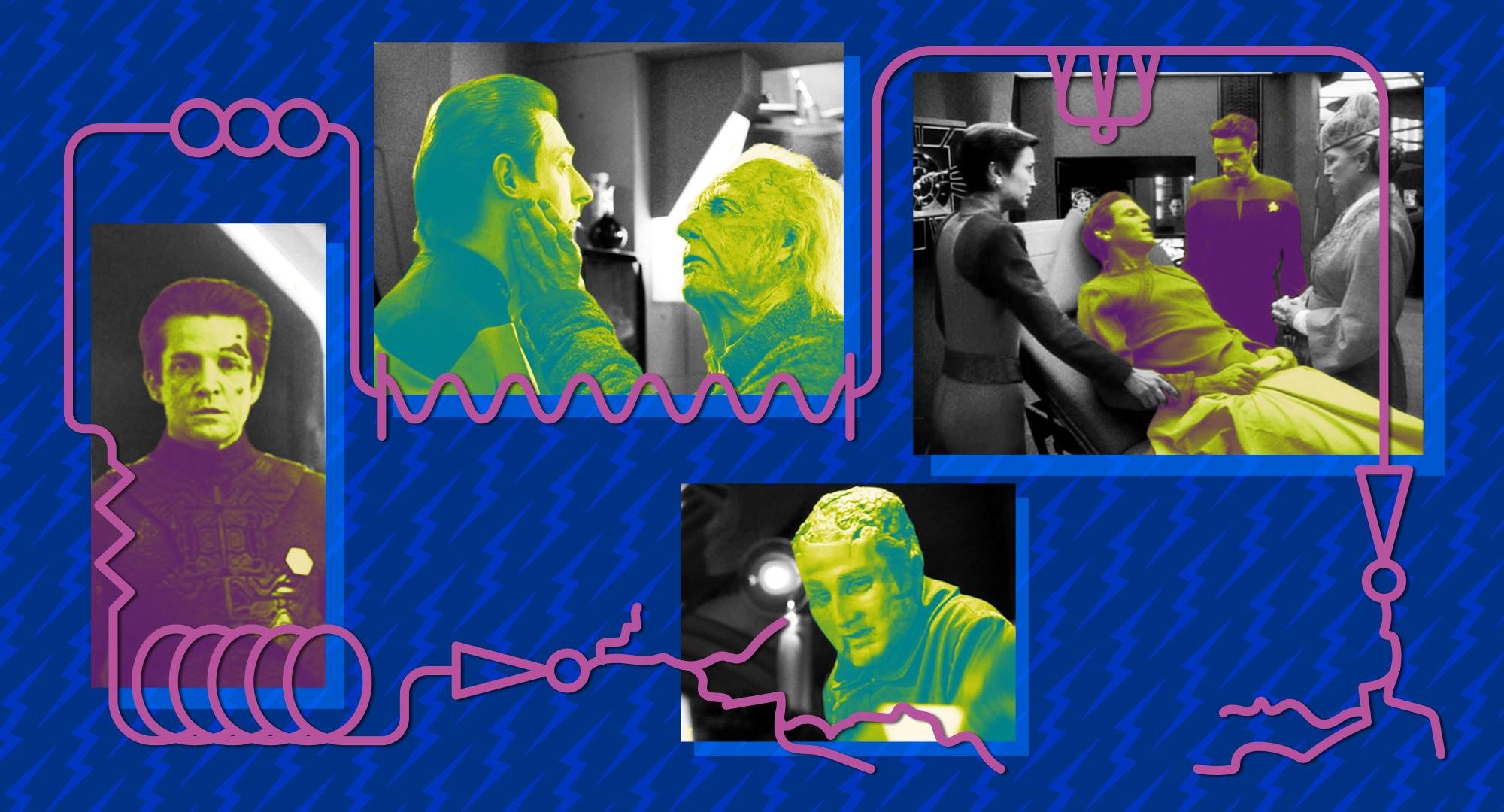

Her classic novel, Frankenstein, made way for a lot of Star Trek's 'creature discomforts.'

StarTrek.com

The product of a frantic, sleepless night on the shores of Lake Geneva in 1816, Mary Shelley’s groundbreaking gothic novel Frankenstein is the nightmare we just can’t shake, even after two centuries. But as much as the iconic story, about an obsessive scientist and the hideous ‘Creature’ he assembles from dead body parts, was designed to horrify and appall its original readers, Shelley’s masterstroke was to give over a large central chunk of the novel to the Creature’s own account of its miserable upbringing. Spurned by all who see it, and driven to murderous frenzies, Shelley’s Creature clings to the hope that Dr. Frankenstein may see the innocent soul within. "The picture I present to you," it tells him, "is peaceful and human."

These days, we tend to think of Frankenstein through the prism of its many cinematic adaptations, which place it squarely in the horror tradition. But unlike other contemporary horror stories, there are no ghosts or vampires in Shelley’s novel. In fact, in her focus on a brilliant scientist deploying the latest technology to blur the boundary between life and death — anticipating the use of organ transplants and electrical defibrillation to revive bodies on the point of total failure — she wrote what many critics argue is the first ever science fiction novel, and one that two centuries later, continues to exert a strong influence on the genre. Every mad scientist, from Doc Brown to Frank N. Furter, owes something to her titular protagonist, while stories of human ingenuity run amok, from Jurassic Park to Terminator, are haunted by the specter of her uncontrollable creation that threatens to destroy its own maker.

"Datalore"

StarTrek.com

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Shelley’s powerful story has made its mark on Star Trek too, with her twin archetypes — of the overreaching scientist and the hideous, misunderstood Creature — playing out again and again on-screen over more than five decades. Sometimes the borrowings are explicit, from Guinan claiming to have befriended Dr. Frankenstein himself in "Evolution," to the crew of the NX-01 debating the relative merits of the novel versus its iconic 1931 adaptation in "Horizon." Elsewhere, the transplanted material is a little less obvious, lurking just beneath the skin of the episode and ready to lurch suddenly back to life in the 23rd or 24th Century.

Here are 10 of the best of Star Trek's Frankenstein-ish creations, from The Original Series through to Picard.

"What Are Little Girls Made Of" (The Original Series)

"What Are Little Girls Made Of"

StarTrek.com

A brilliant scientist bent on transcending death. A hulking creation with murderous tendencies. A mysterious lab hidden away in an arctic wasteland. This quirky Original Series installment might not scream Frankenstein-in-space on first viewing, but so many iconic elements of the story are there once you start to look for them.

Not to mention the casting of Ted Cassidy, famous for playing The Addams Family butler Lurch (based on the Boris Karloff version of Frankenstein’s "monster"), in the role of the villainous Ruk. All we need is for Dr Korby to shout, "It’s alive!" when his ersatz Kirk steps down from the spinning robo-clone machine.

"Brothers" (The Next Generation)

Data, What Are You?

The original and best of Brent Spiner’s three generations of mad scientists (all riffs, of a kind, on Dr. Frankenstein and his warped sense of parental responsibility), this episode features the first appearance of Data’s creator, Dr. Noonian Soong.

Much of the pathos of Shelley’s novel comes from the Creature’s desire to track down the man who assembled it. “You were my father,” it tells Dr. Frankenstein. “To whom could I apply with more fitness than to him who had given me life?”

In this episode, Data is drawn by an unstoppable homing signal to an encounter with his own "father," Dr. Soong. But it is his brother Lore who raises the big question that runs through Shelley’s novel. Is Data’s twin maligned and misunderstood, as their creator believes, or simply irredeemably evil?

"I, Borg" (The Next Generation)

"I, Borg"

StarTrek.com

Shelley’s deep empathy for the hideous Creature is what sets her novel apart from other gothic horror stories. Having spent 10 chapters setting it up as a horrifying antagonist ("wretch," "devil," and "demon" are some of the words used to describe it), she switches perspective, allowing us to see it instead as a pitiable victim of prejudice.

Similarly, when the lone Borg "Third of Five" first beams aboard in this episode, the Starfleet crew see him as nothing more than a temporarily defanged monster. Gradually, though, their prejudice gives way, as they come to recognize the gentle soul beneath the drone’s ugly exterior. If only Dr. Frankenstein’s Creature had found himself on the Enterprise-D! For a start, he might have come away with a name, just like Hugh did.

"Thine Own Self" (The Next Generation)

"Thine Own Self"

StarTrek.com

With his superhuman strength and mild demeanor, Data is something of a gentle giant, not unlike the version of the Creature played by Boris Karloff in the 1930s film adaptations — a "monster" who kills only accidentally or when provoked.

This episode opens with a malfunctioning Data staggering open-jawed into a pre-industrial village, emitting a low moaning sound very much in the Karloff mold. Predictably, it doesn’t take long for the pitchforks to come out, as one villager comments, “He’s not a person. He’s some kind of Creature!”

But despite such treatment, the amnesiac android is still kind enough to save them all from radiation poisoning before they attempt to murder him.

"Life Support" (Deep Space Nine)

"Life Support"

StarTrek.com

It would have been easy for Star Trek: Deep Space Nine to cast the brash young Julian Bashir in the traditional Frankenstein role, doggedly pursuing scientific progress regardless of the human cost. So it was a smart move by the writers of this episode, in which he gradually turns the mortally wounded Vedek Bareil into a thing somewhere between a man and a machine, to have him play the reluctant doctor under pressure to save his patient no matter the consequences.

The echoes of Shelley’s novel are hard to miss here, from the gradual replacement of Bareil’s body parts (including his brain!) to the electrical stimulation required to bring the corpse back to life, but Bashir proves no overreaching scientist but rather a model of restraint, ultimately putting the dignity of his patient above the grand prize of defeating death.

"Faces" (Voyager)

"Faces"

StarTrek.com

Arguably the most successful – and most horrific – of the Delta Quadrant villains, the Vidiians were conceived by Star Trek: Voyager's writers as a race of Dr. Frankensteins, while the gruesome makeup for the Phage-ravaged species was inspired by the composite appearance of the Creature.

In this episode (their sophomore appearance), they also produced the maddest of Star Trek's many mad scientists in Chief Surgeon Sulan. Not content with genetically-splicing B’Elanna into human and Klingon halves, he goes on — in a moment of pure body horror that would have made Mary Shelley blush — to graft the unfortunate Crewman Durst’s face on top of his own.

Guest actor Brian Markinson, who cleverly doubled as Durst and Sulan, obviously wasn’t put off, however – he would go on to play another Frankenstein type two years later in DS9’s “In the Cards,” as Dr Elias Giger, a scientist who aspires to halt death at the cellular level.

"Prototype" (Voyager)

"Prototype"

StarTrek.com

Spurned by human society, Frankenstein’s Creature begs him for a female counterpart so it won’t have to spend the rest of its miserable life alone. In this Voyager episode, a member of a race of artificial lifeforms – who, like the antagonist of Shelley’s novel, are conspicuously above average in size – pleads with B’Elanna Torres to help them reproduce.

Too late, she discovers that the robots have already killed their own "builders," uttering a line that could have been taken straight out of the novel, "My god, what have I done?"

At least, B’Elanna is more successful than Dr. Frankenstein at putting an end to her unholy creation, plunging a knife into its chest and killing it instantly. "It must have been difficult," Captain Janeway observes, "to destroy what you created." B’Elanna simply replies, "It was necessary."

"Drone" (Voyager)

"Drone"

StarTrek.com

Before suffering at the hands of prejudiced humans, Shelley’s Creature has an insatiable thirst for knowledge and self-improvement — very much like a 24th Century Starfleet officer.

Similarly, the advanced drone at the heart of this Voyager installment — created accidentally thanks to a convergence of Seven of Nine’s nanoprobes and The Doctor’s holo-emitter — is desperate to absorb as much information as possible, downloading terraquads of data from the ship’s computer even faster than the Creature thumbs through Plutarch, Milton and Goethe. But despite the new entity’s good nature, and Seven’s exemplary parenting, a happy ending proves equally impossible here. "I was never meant to be," the Borg tells a heartbroken Seven, as it terminates itself to save the ship.

"Horizon" (Enterprise)

"Horizon"

StarTrek.com

Just who the real "monster" is in Frankenstein is a vexed question, and one that an extra 150 years of debate has clearly failed to answer.

In this episode, when Commander Tucker proposes a marathon of the classic monster films for the NX-01 movie night, T’Pol suggests the crew should read the novel instead. But while Trip ridicules her desire for a book club, not to mention dismissing Mary Shelley as "the wife of a famous poet," her interpretation of the iconic 1931 movie is very much in line with the more nuanced position of the source material. “From my perspective,” she tells her colleagues, “this was the story of an individual persecuted by humans because he was different.”

Is T’Pol winding Trip and Archer up with her sly Vulcan humor, or is she simply a more sophisticated viewer than they are?

"The Impossible Box" (Picard)

"The End is the Beginning"

StarTrek.com

Nearly 30 years on from “I, Borg,” Hugh proves once again to be the ultimate poster-Borg for redemption. In its portrayal of the xBs, Picard recasts Star Trek's most formidable — and most monstrous — villains in a light that engenders pity rather than fear, and it is Hugh’s compassionate desire to help as many of these wretches as possible that encourages others to see them differently as well.

“You're showing what the Borg are underneath,” Picard tells him. “They're victims, not monsters.” Later, when he learns of the former drone’s death, he makes an observation that could apply just as well to Frankenstein’s Creature. “Poor Hugh,” he muses. “It must have taken appalling brutality to turn such a gentle soul to violence.”