Published Oct 10, 2023

When Amok Time Became a Mirror

For World Mental Health Day, one fan shares what it was like to watch this pivotal episode for the first time and see their own experiences detailed in an unexpected way.

StarTrek.com | Getty Images

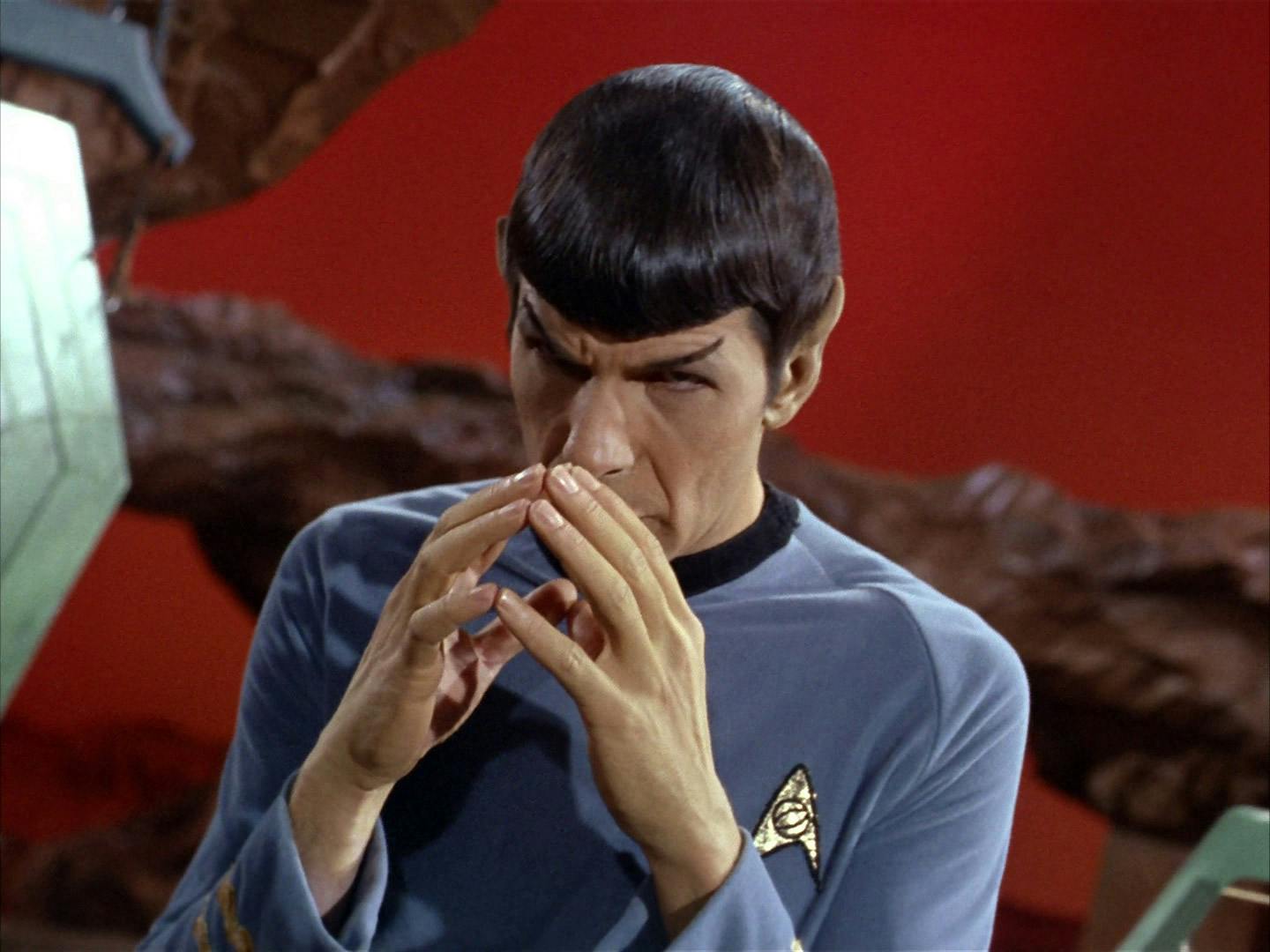

I’m friends with a lot of trans and disabled people, so the words “meat sack” get thrown around a lot in my social circles. Meat sack: something raw, dead, destructible. Something that exists only to hold what’s real. I’ve been thinking a lot about Spock’s relationship with his body, and trying to figure out if that’s a framework he’d be into. Currently, I’m leaning against. ‘Meat sack’ may be designed to create distance from the body, but its viscera still implies that the body exists. To entirely dissociate, you have to find some way to believe that your body isn’t real at all, despite all evidence to the contrary.

Of course, Spock would never ignore evidence. But that doesn’t mean he needs to acknowledge it if it’s not directly relevant. Watching Spock is a tremendous comfort. He tells us, again and again, that what he is is logic. He is a concept whose role is to put together other concepts. Sometimes, he has to take physical action to implement those concepts, but that’s a tertiary reality at best. His friends and colleagues may raise their eyebrows at his claim, but he knows who he is. It’s easy, as an audience, to believe him. After all, he’s half Vulcan. Maybe it really is possible for him to not experience his body. And he’s half human, too. If he can do it, maybe so can we.

"Amok Time"

StarTrek.com

We can’t. He can’t, either. If you ignore your body speaking to you for long enough, it will start to yell. In Spock’s case, literally. The first time we see him in “,” he’s raising his voice at Chapel, cruel in a way we’ve never seen. It all gets medicalized very fast. Bones believes it would be impossible for Spock to do such a thing; therefore, it must be Spock’s body acting on its own, a separate entity from Spock himself. Spock refuses to be examined in any way. He knows that any examination of his physical self would show a biology that revealed him in a way that went beyond the facts of blood and broken bones. He’s trying to believe that if he could just try hard enough, he could contain himself and keep his body and its implications private.

We don’t know much about how brains work. We have some ideas, but explanations of most brain processes end with a shrug. What we know about mental illness is more often based in observation than science. I learned a lot about hypomania when I got my bipolar diagnosis. Sometimes, hypomanic episodes happen because you’re too excited about something, or you’re doing too many things too quickly, or, commonly, when seasons change. But sometimes they happen because you’re dealing with something difficult, and your brain is trying to protect you with a distraction so intense that you can’t possibly think. It is very effective.

"Amok Time"

StarTrek.com

I’m working on this, but as things stand, I find hypomanic episodes to be humiliating. I feel like everyone can see what I’m reacting to, and I feel immature and selfish for taking up time and space. I first watched “Amok Time” with some friends relatively soon after my diagnosis. They were extremely excited to show it to me. I had been promised excessive subtext and a bottle of champagne. It quickly became clear to me that I was having a very different experience of the episode than they were. They were seeing sublimated desire, and I was watching Spock’s uncontrollable biology mirror my own. All I wanted was to keep it together, and I was watching Spock fall apart. I managed not to yell like he did, though I did slip and drop the champagne.

"Amok Time"

StarTrek.com

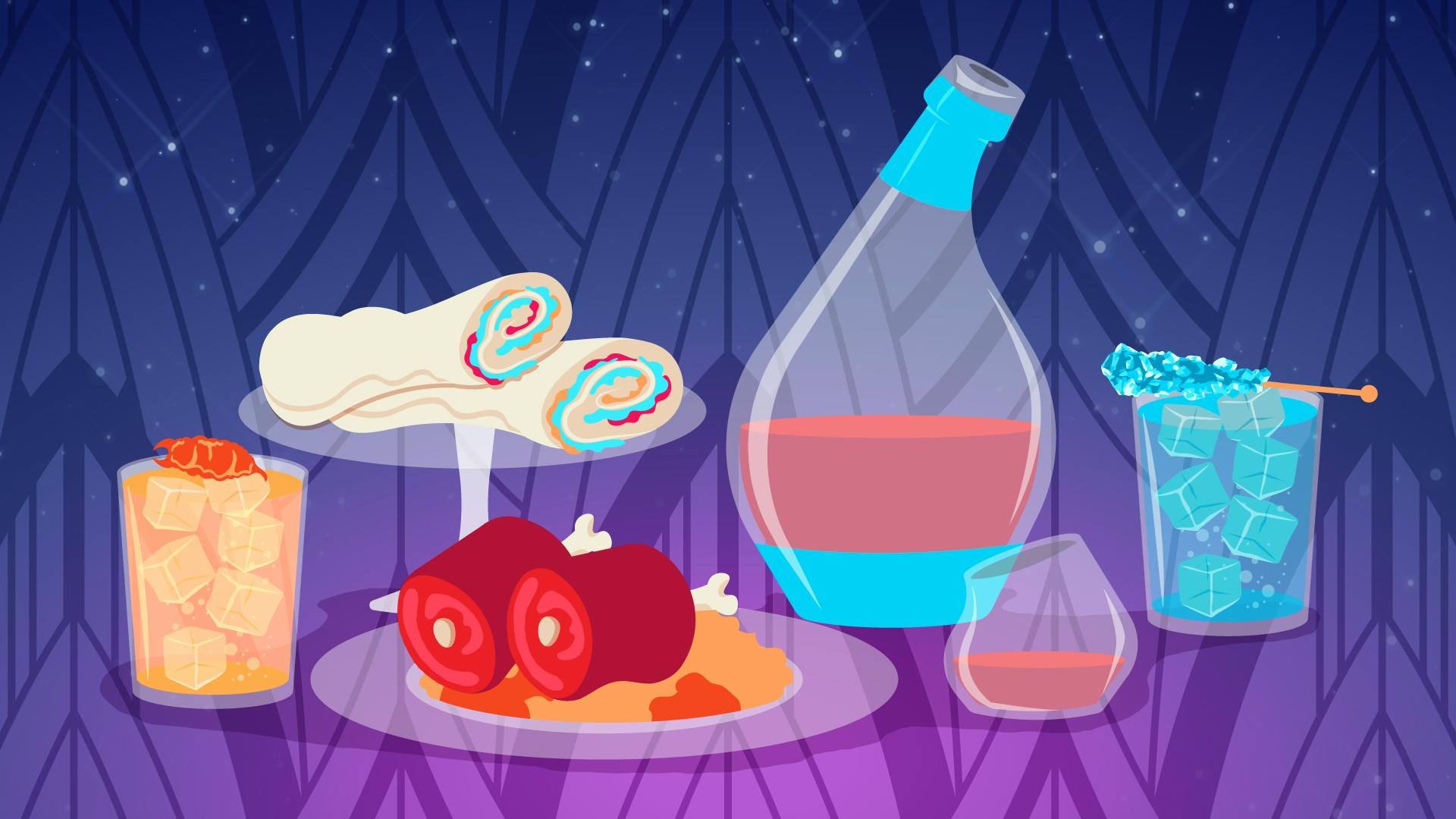

Usually, we use the term “birthright” to mean something passed along, often representative of some sort of power. Family heirlooms, surnames, the crown. But pon farr is a birthright, too. Spock can try to abdicate all he wants, but there’s only so far you can run from your own literal blood. I wonder if knowing what was happening comforted him, or horrified him more. Not that they’re mutually exclusive. On one hand, there’s a very clear logic to pon farr. There was something in Spock’s blood that every Vulcan before him had experienced and every Vulcan after will, too. He could list the symptoms, and recognize them when they happened. On the other hand, his body had taken an oath. He knew what was going to happen next. He knew he didn’t want it. He knew he couldn’t stop it.

I self-diagnosed on the second day of my first hypomanic episode. I’d long suspected my decade-old depression was abnormal. My family has a history of vivid and undiagnosed mental illness, including negative reactions to SSRIs, a common anti-depressant that doesn’t work for bipolar people. I have a close friend who is bipolar, and I listen when he talks. I’d been researching symptoms for years. It took me weeks to get official confirmation, but I didn’t need it. Like Spock, I knew exactly what was coming, and all I could do was try to mediate it. He asked to be locked away; I tried to control the excessive spending ‘symptom’ by only buying things that were on sale.

"Amok Time"

StarTrek.com

There’s comfort in knowing, but the comfort is impure. It’s mixed with anger and fear and sorrow. If we knew this was possible, why didn’t my family prepare me better? Is there any way I could handle it better than my ancestors? If we had the knowledge and the meds and the healthcare access at the time, would my great-grandmother have gotten help, and would that have changed the most painful parts of my family history?

But there’s something else, too. There’s a promise of where you’ve been. Spock and I did not simply pop into history fully formed. There is a history of family and community and biology. Our bodies are inheritances. When Spock is experiencing blood madness, every Vulcan that has been and will be and currently is are making their way out of the woodwork of his veins. When my head does the thing where my internal monologue is nothing but a scream, I know that some of the screams are mourning Sicilian women whose names I’ll never know. I don’t know that that makes it easier, per se, or more pleasant. It might make it worse. But no matter how alone we are, we’re filled with a history we can’t untangle ourselves from.

"Amok Time"

StarTrek.com

About a year after the party, I watched “Amok Time” again. There was a lot I’d missed the first time. There was, in fact, more subtext than I had even begun to parse. There was an outstanding rip in Kirk’s uniform. But there was also something I’d skipped over entirely.

When Spock tells Kirk that he thinks Kirk will find his behavior distasteful, Kirk replies mildly: “Will I? You’ve helped me through a lot.” When Spock is fully in pon farr, or I am fully in an episode, it can be all-consuming. But we exist beyond that consumption. Bones was worried about Spock, and Kirk tried to communicate in ways that Spock would be able to understand. I dropped the champagne, but there were people who’d brought it over in the first place; they would worry, they would communicate. Our bodies are our worlds, but the world is not our bodies.