Published Sep 11, 2019

Would You Put a Holodeck in Your School?

An educator’s look at the pros and cons of using holonovels in the classroom.

StarTrek.com

My classroom library is space-themed for good reason. The nine mismatched shelves of donated books stand beneath Hubble images of colorful galaxies and spinning planets. “Discover New Worlds,” reads one handmade banner says. “Read. Explore. Enjoy,” proclaims another.

Stories of fascinating fictional realms have always drawn my curiosity toward the stars, and now in my role as a high school teacher, the connection between reading and futuristic environments seems even clearer. In Voyager’s “Persistence of Vision,” Captain Janeway encourages Seven of Nine to utilize the holodeck as a place to unwind in a creative setting. “Imagination frees the mind,” she says. “It inspires ideas and solutions.” The Captain is correct (as usual), and her take on technology couldn’t be more relevant to American classrooms today. While the holodeck is mostly utilized by Starfleet for recreation and training purposes, I would argue it is an ideal place for students to build a love of narrative and engage with reading in a participatory way.

First introduced as the Rec Room on The Animated Series episode “Practical Joker,” the holodeck has become a standby of Star Trek storytelling. Its opening appearances in both TAS and The Next Generation saw it generating a relaxing forest escape for off-duty crew, and recreation remains the overwhelming purpose across all series, from Bashir’s secret agent saga (“Our Man Bashir”), to Paris’s Captain Proton escapades (“Bride of Chaotica”), to recurring hangouts like Vic’s Las Vegas Lounge (“It’s Only a Paper Moon”). While sometimes criticized as an overused plot device, from scientific discovery to combat drills to practicing on how to navigate social situations, the holodeck is nonetheless an important tool in Starfleet life. Star Trek would not be nearly as interesting without the holodeck.

Its propensity to malfunction notwithstanding, a holodeck would be an advantageous addition to real-world classrooms in many ways. The most obvious use is for field trips to places not easily accessed due to distance or budget constraints. But, schools could also benefit from adaptive calming spaces. Today’s youth face high levels of stress, and many states, including my home state of Michigan, are delving into social-emotional learning and teaching self-awareness of needs. A holo-space, even a small one, would provide a customizable corner of peace.

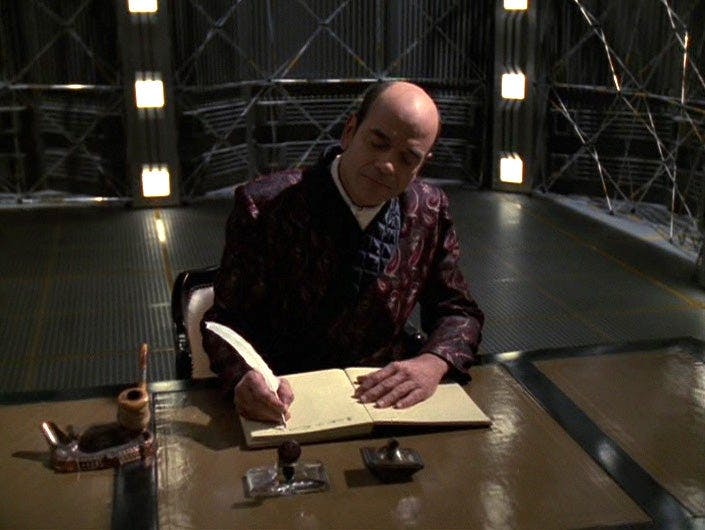

In English classes, I can envision using holonovels in several ways. They could help students experience classic literature, as in Janeway’s gothic novel (“Cathexis”), rehearse drama like Picard and Data in “The Defector,” compose stories as the EMH does in “Author, Author,” and exercise deductive logic like our favorite android-turned-detective in “Elementary, Dear Data.” As Riker demonstrates in the Enterprise finale, holodeck programs can be run in objective (observation only) mode or subjective (interactive) mode, and both have their advantages in a classroom reading setting.

Want to have your student witness the creation of Frankenstein’s monster firsthand as it is described in Shelley’s masterpiece? Use objective mode. Want to let them work out the complexities of communal politics in Lord of the Flies? Offer subjective mode. Students who have dreamed about becoming Hermoine Granger or visiting Narnia would undoubtedly be fully engaged in such learning exploration, and reluctant students who wouldn’t otherwise pick up a challenging text may be drawn in if they get to travel Route 66 with the Joads for a few chapters, help the Younger family vacate their apartment, or fix a Hab unit on Mars. In this way, holonovels would offer a useful accommodation to striving readers, as well as a constantly-adapting challenge for enthusiastic readers.

StarTrek.com

I feel the most exciting application of holonovels is for greater options in independent reading, a widely-recognized best practice in education pedagogy. In her introduction to Book Love (2013), a text that helped launch the independent reading revolution in the U.S., author Penny Kittle writes, “We must connect students to books that force them to pay attention, to think and wonder, to imagine and believe, and then read for the rest of their lives.” The point is to get students to “own their reading” using guided choice to discover books that bring them “joy and escape” while offering increasing volume and complexity. Independent reading is meant to be implemented alongside shared class texts, not in place of them, and is accomplished through regular practice and frequent student-teacher conferences.

Adults in Star Trek frequently engage in independent (non-mandatory) reading — Picard on Risa in “Captain’s Holiday,” T’Pol with the Kir’Shara in “Daedalus,” etc. In the rare instances when we get to see school settings in Star Trek, we find students reading on PADDs, laptops, even a Cardassian version of a smart board in Keiko’s classroom on Deep Space Nine. Similar to today, Starfleet kids are expected to learn subjects they might not be thrilled about (looking at you, calculus-hating Harry Bernard), but they also engage in instructive narratives for fun in the form of holoprograms such as The Adventures of Flotter, a favorite of Voyager’s Naomi Wildman (and seemingly everyone else onboard). The Star Trek universe clearly has space for independent reading and explorative learning for all ages, and our current U.S. education system would benefit from welcoming a wider array of research-supported reading technologies, including holo-stories, if and when they are invented.

Some might argue that participating in a holonovel isn’t the same as reading a “real” book, and in the sense of decoding written language, it isn’t, but a holonovel still requires tracking of characterization, setting, conflict, etc., and requires more active engagement. Audiobooks have recently met similar scrutiny, but studies have concluded there is no discernible loss of benefit to listeners. As Time reports, Beth Rogowsky of Bloomsberg University found that participants who listened to a book versus reading it demonstrated no significant discrepancy in comprehension. The article notes that audiobook listeners are prone to distraction by surroundings, but that would be a non-issue in a holodeck program with 360-degree immersion. Melissa Dahl’s conclusion in her article in The Cut is that audiobooks are not “cheating,” but simply another form of reading, and I believe holodeck technology fits that description as well.

Of course, there could be ethical considerations to work out regarding holodeck usage in a school setting. While young-yet-precocious Naomi Wildman is not disturbed at seeing Flotter vaporized as part of a holoprogram in Voyager’s “Once Upon a Time,” it is conceivable that some students might react more strongly to difficult content displayed realistically. Some experts, including Howard Skylar of the University of Helsinki, believe that the emotional responses provoked by fictional characters are just as strong as those provoked by real people and situations, and while this is an excellent way to build empathy, it raises valid questions. Can a high schooler handle witnessing Gatsby die in his pool, or Ophelia drown herself, or Grendel tear apart the warriors of Herot in all the realness of a holographic simulation?

StarTrek.com

While I tend to agree with Paul Ringel in The Atlantic that banning books usually does more harm than good, particularly along the lines of cultural marginalization, the decision of what is appropriate content for a given age group is a decision best left to individual communities. The beauty of independent reading is that it is choice-driven; if a student doesn’t like a book or is uncomfortable reading a text they’ve chosen, they are free to abandon that book and select something that is a better fit for their goals and preferences, with instructor guidance. As with all types of media, quality content is key: kids need accessible prose generated by diverse and authentic voices in culturally sensitive ways, regardless of how they are consuming it.

Although holographic rooms and replicated matter might seem centuries in the future, current virtual reality technology is rapidly advancing. The VR demos I have seen (my favorite is Senza Peso by Kite and Lightning) were nothing short of transcendent in their ability to transport me to another world, and industry professionals are already making the logical leap to classroom instruction. In a 2018 CNN article, author Emma Kennedy reported that edtech companies are finding a correlation between VR usage in lessons and increased student engagement, and researchers see benefits to adding VR alongside existing teaching tools (within the purview of an expert educator). As the article notes, wide scale implementation of VR in classrooms is currently limited by device access and availability of quality content, both of which should become more affordable/plentiful over time, especially with the influence of the gaming and film industries. In the meantime, there are some lower-tech options — interactive fiction and even those beloved old-schoolChoose Your Own Adventure books — that could be considered steps in the evolution of reading, and forerunners of the holonovels to come.

Even though the march of technology can be exciting, as a lover of all things literary and a hoarder of paper books, I do not believe printed material has to become extinct in order for holonovels to take root. When ebooks debuted, many feared paperbacks were toast, but recent market data shows that they are not going anywhere. We as a society, like Captain Picard with his ubiquitous Shakespeare volumes, are enamored with being surrounded by books, the weight of their pages in our palms, their biblichor in our nostrils. We are a species of storytellers, and that tradition will continue regardless of what new media is invented, yet these innovative technologies offer opportunities that, when added to the existing spectrum of education tools, increase the chances that students have to learn and “work to better [them]selves and the rest of humanity” as Picard so famously states in First Contact.

The benefits of reading are varied and vast, and just as humans have been telling stories since the dawn of time, so it will continue into the stars. Reading is worthwhile in any capacity, whatever technologies or approaches we use, and as this next school year kicks off, I am excited to inspire my students to explore strange new worlds in stories, however they might manifest.

Kelli Fitzpatrick (she/her) is an English teacher and Star Trek: Strange New Worlds author currently writing for the Star Trek Adventures role-playing game from Modiphius. She has several essays on sci-fi media in books from Sequart and ATB Publishing, and online at Women at Warp, and can be found at KelliFitzpatrick.com and @KelliFitzWrites.