Published Feb 13, 2011

Watson vs. Jeopardy! Champs & the Trek Connection

Watson vs. Jeopardy! Champs & the Trek Connection

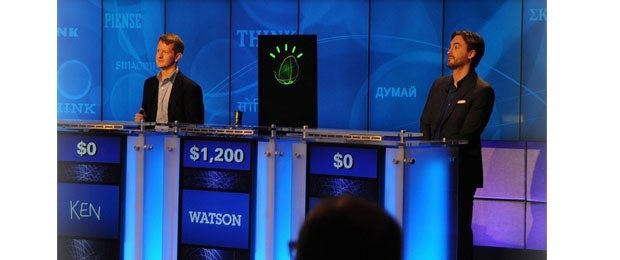

It’ll be a battle for the ages. This week, from Monday to Wednesday, the game show Jeopardy! will pit IBM’s supercomputer, a talking and thinking device named Watson, against two of the show’s greatest all-time champs, Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter. The hype surrounding the event has been right up there with the advance publicity that accompanied the chess-match showdown between IBM’s Deep Blue and then-reigning champion Garry Kasparov. Not surprisingly, several members of the IBM team that spent seven years on the Watson project were inspired by Star Trek and, more specifically, the talking/interactive computer aboard the U.S.S. Enterprise NCC-1701. StarTrek.com recently caught up with one of them, Dr. Christopher Welty, a computer scientist and member of the IBM artificial intelligence group that helped bring Watson to life.How big a Star Trek fan are you?

Welty: Oh, pretty big. I used to go to conventions and I’ve even spoken at a few of them. I’ve been a fan of the show since it was first on in the 1960s.Would you say Trek influenced you in your career choice?Welty: Definitely. I was probably more interested, as I was growing up, in getting my education in space travel than I was in computers, but I sort of came to computer science when I was up in college. That developed my passion, but I’ve always maintained an interest in combining the two. I was actually always impressed, when I started to understand computer technology, the ship-board computer in Star Trek. It’s an incredibly useful tool. They never really spent that much time investigating that technology in the show, but in the mid-1980’s I actually met Gene Roddenberry and he was very passionate about the use of computers as a tool. It was something, in a sense, that all the people in the Star Trek crew took for granted. It was just an incredible useful technology that they used all the time and they interacted with it in English, which is not the way we interact with computers today.Take us to creating Watson. What was the mission you and the rest of the IBM/Watson team were on?Welty: We were all working in natural language processing, just trying to get computers to better understand English. This was inspired, really, by a combination of trying to think of the next great challenge for IBM Research to tackle and Ken Jennings’ 74-game Jeopardy! streak. Those two things came together and someone say, “Hey, what about playing Jeopardy! as the next big challenge?” When the executives at IBM came up with that idea, they naturally came to us because we were already working in that general area. So it wasn’t necessarily because of Star Trek that the idea came up, but once we started, we started imagining that the general public might associate the project with HAL (from 2001: A Space Odyssey). There’s this legend about each letter of HAL being one letter previous to the letters IBM. We work for IBM, but we know nothing about that other than that Arthur C. Clarke went to his grave denying that was an inspiration.Anyway, we expected that people would have that association with HAL, and we wanted the association with the Star Trek computer. That is what we are building. We are building a technology here that I think, in 10 years, people will take for granted that they interact with computers in their own language. And they will probably forget about things like keyboards and mice. They’ll be relics like corded phones and typewriters.Most people are comparing the Watson vs. Jeopardy! champs battle to the chess matches between Deep Blue and Garry Kasparov. How fair a comparison is that?

Welty: I think it’s a fair analogy. I think this is much harder than chess and, honestly, I think Jennings and Rutter are much smarter than Kasparov, though a lot of traditional scientists will probably find that offensive, because chess used to be a measure of intelligence. But I think in today’s world we understand that human intelligence has a lot of dimensions, and the kind of intelligence that makes someone a good chess player is not the only kind. In that sense, I think Jennings and Rutter are much smarter, and their capabilities in this game are really amazing, the way they stack up against that average human.The three Jeopardy! episodes will not air live. So, without giving too much away, how did Watson perform?Welty: It’s not an embarrassment for anyone, which was certainly a worry we had going into it. We built it to play at this level. A lot of people talk about the Deep Blue Challenge and how Kasparov won one game and it was only a three-game, but if you pit Deep Blue against the average person, he’ll beat almost everyone. And I think what we have here, in the case of Watson, is a machine that has what we call a “broad domain.” You can ask questions about just about anything. Watson is way above the average human performance level and up there at the level of these Jeopardy grand champions. It’s an exciting game.How much raw processing power are we talking about with Watson?Welty: Watson has roughly 2,000 CPUs. It’s kind of a difficult measurement because the CPUs are connected in a very special way. It’s equivalent, we’re saying now, to about 6,000 desktop computers, but again, they’re connected in this special way that makes it possible to put all this information together in the one or two seconds it takes to be competitive in Jeopardy!Clarify something. Watson is not connected to the Internet, right? It operates using its own, built-in data sources?Welty: That is correct. It’s mostly English-text sources and that’s all self-contained during the match.So what advantages might a human have over Watson? Doesn’t Watson have to think something through, find the answer, determine the odds, finalize a decision and then buzz in, whereas a human can almost do both at once, almost involuntarily?Welty: Good point. The intelligence behind Watson is fundamentally different from human intelligence. In the way that Deep Blue didn’t play chess at all the way people play chess, Watson doesn’t play Jeopardy! at all the way people play Jeopardy! So, for people, the big challenge in Jeopardy! is knowing the answers to these questions. The possible areas that Jeopardy! can ask questions is enormous: history, geography, entertainment, math, science. It’s all over the spectrum. For people, it’s just knowing that much. For the machine, we have the answer to almost every question somewhere in our sources. So the challenge is understanding the question and understanding the sources well enough to know that they answer the question. It’s something, again, that we (as humans) take completely for granted. People playing the game don’t spend a lot of time understanding the questions. They spend their time trying to come up with the answer. The second thing is that people often know they know the answer to the question before the answer even pops into their head. They’ll see the question and know they know the answer. So they’ll know they’re ready to buzz. Watson can’t do that. So, Watson has to generate its answer and has to calculate whether it’s confident enough in that answer to buzz because, of course, in Jeopardy if you buzz in and you’re wrong you lose money. You can’t just buzz in every time. So it needs to do all of that before deciding to buzz. So, yeah, people have a slight advantage in that sense. Watson has a slight advantage back in that if it does get all that done in time it’s very consistent about the speed at which it buzzes. People can be faster or slower. They have a standard distribution, so sometimes they’re faster and sometimes they’re slower.Where does the IBM go from here with Watson and the technology developed for it? What are the intended real-world, practical applications?Welty: Since we are a research team, we chose to point Watson at the medical domain next. It is incredibly difficult and challenging, and there are some remaining research issues to address. For example, while Watson has a surprising -- for a computer -- command of English, making a medical "information assistant" requires dealing with information from many different sources: doctors notes, patient and family history, basic reference materials, anatomical structures, clinical trials, test results, X rays, MRIs, and on and on. Outside of research, I believe IBMs customers will determine where Watson goes next. I hope to see it applied in a number of different places. Any profession that depends on information that is constantly being updated is a potential application of Watson. Professionals are literally incapable of keeping up with all the information that might be relevant to them, letalone their own email inboxes. But don't forget, just the ability to interact with a computer using natural language will change a lot of existing systems. I hope to see that soon.In your view, how prescient has Star Trek been when it comes to science and technology?Welty: Well, I’m a fan, and think Star Trek is incredibly prescient. I met Roddenberry and, even though he wasn’t a technical person, he really understood the future role computers will play in society. They are tools. They are not really things to be afraid of. If you look at the Star Trek computer, it’s a tool that everyone used to do what they needed to do. Data (on TNG) was the best person in the crew at the time. He was really, in a sense, an idealized person. He always acted the right way unless someone else had taken control of him. So there was always this very positive message about the role that computers will play in the future. As a person working on that, that’s certainly our intention, that computers be tools that help us deal with what we have to do. Right now, most professionals are inundated with information and they have no way to keep up. We need computers to help us sort through all that information. And that’s the kind of computer that Watson is.Actually, you mentioned HAL before. Do you ever worry about Watson becoming a HAL or even, since you mentioned Data, a Lore?Welty: I don’t worry about it, and I’ll tell you why. Watson doesn’t have the problem HAL had. Arthur C. Clarke explained later on that HAL had been lied to and just didn’t know what it was supposed to do anymore. In the case of Watson, if you deal with natural language, you have to be capable of understanding that there’s such a thing as a lie. Watson gathers evidence from a lot of sources and it learns what to trust and what not to trust. Even when a trusted source is wrong, it’s capable of dealing with that and comparing it with evidence it’s getting from other sources. So that’s an important thing that’s necessary if you’re dealing with natural language. But it is a machine. It’s not deciding. It’s a support tool for people who make decisions. Right now, you’d be better off fearing your bicycle is going to take over the world than a machine like Watson. It’s really just a tool to use. And Lore? The builder realized there was something wrong with him and turned him off.

Check local listings to watch the Jeopardy! IBM Challenge this week and see if Watson can beat the show's all-time champs.