Published May 22, 2012

TOS Director Ralph Senensky, Part 1

TOS Director Ralph Senensky, Part 1

Ralph Senensky just turned 89 years old, but you’d never know it from talking to the man. He sounds half his age and his memories are crystal clear, which makes reminiscing with him about directing six and a half episodes of the original Star Trek – and his long career -- that much more exciting and revealing. Six and a half episodes? He helmed “This Side of Paradise,” “Metamorphosis,” “Bread and Circuses,” “Obsession,” “Return to Tomorrow,” “Is There in Truth No Beauty” and part of “The Tholian Web.” He actually went uncredited on “The Tholian Web,” and the story behind that occurrence is fascinating. Below is part one of our two part interview with Senensky, and check back tomorrow for part two.

You directed a handful of episodes of a relatively popular sci-fi show, a little something called Star Trek, back in the late 1960s. Here we are, 40-plus years later talking about it…

Senensky: It was worth doing if only to have directed “This Side of Paradise” and “Metamorphosis.” Those two shows alone made it worth doing. The other ones, I only discount “Return to Tomorrow.” That one just didn’t work. On my website, when I started it, I said that although I did not do Star Trek until six years into my career, I chose to start my site talking about Star Trek because that’s the show – even though I did so many other shows – if you Google my name, you’d think I spent my whole career working on Star Trek. I’m not sure I made any specific contribution to Star Trek beyond directing some good episode. By the time I got to Star Trek, it was almost the end of the first season, and things were pretty well set. So it was just a matter of coming in and doing my thing within that arena.

What do you remember of receiving that first telephone call about directing Star Trek? You were originally supposed to direct a different episode of the show, right?

Senensky: Exactly. I got a call from my agent telling me they had a request for me to come to Star Trek. Was I interested? I said, sure, and so they booked me. They sent me the script for "The Devil in the Dark." It was a script by Gene Coon. I knew Gene because I’d directed two episodes of Wild Wild West, which he produced. It was in December, so I was going back to Iowa to spend the holiday with my mother and my family. After I got back I received a notice from the studio, and they sent me the script for "This Side of Paradise." They said they’d switched the episodes. I never knew why they switched. I wondered at the time – and later, too—if maybe Joe Pevney had been assigned to it and didn’t like it. That was just a thought that had come to mind.

Anyway, I read the script and I was disappointed because "The Devil in the Dark" was a darker script and it was different than things I’d done. "This Side of Paradise," except for the science fiction things that happen, was a story not unlike other things that I’d already been doing. But I went ahead and once I got into it, it really proved to be very, very, very well worthwhile doing. Leonard (Nimoy) and Jill (Ireland) were wonderful, as was the whole cast. It was the material that, as I say, I was well acquainted with. So, in a way, it might have been better that I went in doing that because, as I say, the science-fiction aside, it was familiar territory to me.

What stands out to you most about the shoot?

Senensky: Several things. One of them was Jerry Finnerman, the cameraman, who was marvelous. I liked the fact that so much of it was done on location. I had broken into location work doing Route 66 and Naked City, and I liked that. I liked working on a soundstage, but I really did like getting outside, and “This Side of Paradise” just adapted well to being out in the terrain we found to do it.

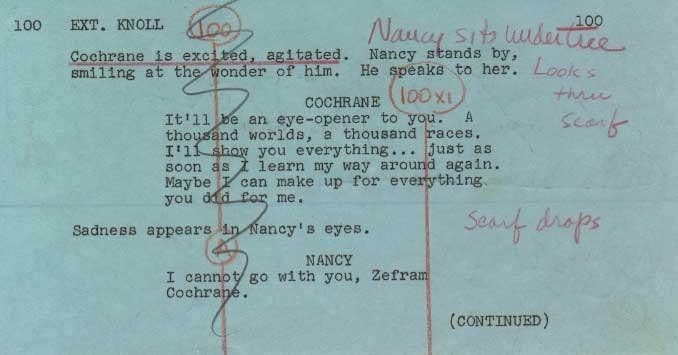

Next up was “Metamorphosis.” You’ve said that this one is actually your favorite of the Treks you directed. Why?

Senensky: Number one, the script. I just thought the script was absolutely wonderful. It was also by Gene Coon. As I remember Gene, he was the least author-y type of person. He just didn’t seem like an author. He didn’t present that kind of sensitivity that his writing had expressed. It was just a deep, deep script and scene after scene had so many angles to come at it from. It was a complex script. Then, visually, we had two sound stages, one for the Enterprise and one for the swing sets. Those sound stages were at the end of the lot at Desilu and they were not large. They did not compare at all to the size of the stages and lots I’d been working on at Metro, at Warner Bros., but the one sound stage for the Enterprise, the sets took up the whole stage. Then, right next to it was another stage, where they did the exterior work.

As I say, these were not large stages, but Jerry Finnerman wanted to give the feeling – which the show needed – of being on a really deserted planet. He wanted to give it space. Jerry recommended using the 9-millimeter lens, the fisheye, which I was not acquainted with. I was still fairly new to camerawork. So I was still learning. We used the fisheye, and the end result is there are shots in there where it looks like the shuttlecraft is a football field away, when it was really just five long paces away. If Glenn Corbett was to move from his position by the camera to the shuttlecraft, it was five or six long steps. Jerry decided to do a purple sky, which was beautiful. He added clouds, which we did with the bee smokers. It was a very, very creative set. The whole of Desilu – and it was a smaller studio – there was a great atmosphere to work in.

Up next was “Bread and Circuses…”

Well, that all changed now. Before, we’d have a 7 or 7:30 a.m. report call to prep for an 8 o’clock shoot. We’d shoot until 7 o’clock at night. If you had to go over, you would go over. We didn’t usually go over. Gene Coon told me, when I arrived to do my very first show, that they had a six-day schedule, but that some of the shows did go into a seventh day. So they were averaging out about six and a half days per episode. That was all changed. Now, the number one edict from the upper echelons of Paramount was that the shows would be done in the six days. Not only that, but we would no longer shoot until 7 o’clock at night. We would quit at 6:12. That was 48 minutes a day times six days. It’s just minutes less than a half day. So they now wanted Star Trek to be done in five and a half days.

That just brought a great pressure. There was just a different feeling at the company, just knowing that that was there and that they were hovering. I think that affected the work. I was never as satisfied with what I did after “Metamorphosis” compared to what I did on the first two shows. Even when you were working hard, there was a tension, and it’s hard to be tense when you’re doing creative work.

Check back tomorrow for part two of our exclusive interview with Ralph Senensky. Click HERE to watch a career-spanning video interview with Senensky conducted by the Archive of American Television. And be sure to click HERE to visit his site/blog.