Published Dec 21, 2013

STARLOGGING WITH DAVID MCDONNELL: Picking Photos For Starlog

STARLOGGING WITH DAVID MCDONNELL: Picking Photos For Starlog

At 1 p.m. on a Friday in December 1982, I reported to the Golden Harvest Company’s luxurious offices in Los Angeles. I had just flown in from New York. My mission: Select the photographs for the Official Movie Magazine I was editing. My first.

Publicist Al Ebner (I think) presented me with the plastic-bound folders of black and white and color photo contact sheets from Golden Harvest’s High Road to China. I was to study each image (double the size of a postage stamp) with a photographer’s loupe (an eyeball-sized magnifier), make my selections and write down the I.D. numbers so dupes could be made. I only had about 14,000 photos to look at. Yes, 14,000.

Maybe you remember this Raiders of the Lost Ark wannabe, directed by Where Eagles Dare’s Brian G. Hutton, starring Tom Selleck? Although a Starlog staffer for just 10 weeks, I landed this gig because I actually knew something about the flick (having edited an article on High Road to China while at Mediascene Prevue earlier). As a major (if now obscure) motion picture, a unit photographer had been on set every day of lensing, taking lotsa pix.

But who can look at 14,000 photos in four hours? I was neither Superman nor the Flash. Since the Golden Harvest office was closing, I was allowed to borrow the remaining unexamined photo "books" and adjourn to my hotel. I met up with Lee Goldberg, then an UCLA college student, whose interview with Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan scribe Jack B. Sowards ("The Man Who Killed Spock") arrived on my desk the October day I started at Starlog (I bought and published that freelance submission, his first professional sale, in issue #67). After dinner with Goldberg (later a TV writer-producer of Diagnosis Murder and the author of 15 terrific, original Monk mystery novels), I fled to my room, stayed up all night and finished the "High Road to Hell" photo-editing ordeal.

Saturday, I lodged the photo binders with the hotel clerk (for pickup by Ebner) and lunched with two other pals. With time to kill before my plane that evening, one stashed me at his house and I watched, on videotape, a film I had completely missed in theaters that year, Star Trek II. (SPOILER ALERT!) Spock dies! Little did I know that 12+ months later, I would be editing the Star Trek III: The Search for Spock Official Movie Magazine. (SPOILER ALERT!) Spock lives!

That project involved a much shorter odyssey—a crosstown journey in Manhattan from Starlog’s offices on Park Avenue South to Paramount Pictures, then high in the Gulf+Western Building on Columbus Circle. Paramount publicist Tom Phillips (our longtime film studio PR liaison) set me up with the Trek III contact books—and I was delighted that there weren’t 14,000 endless pix to check out, just a few thousand. We could convert color images to black and white for the black-and white pages, so I only had to search through the color "art" (as photos and all graphics, including actual artwork, are known).

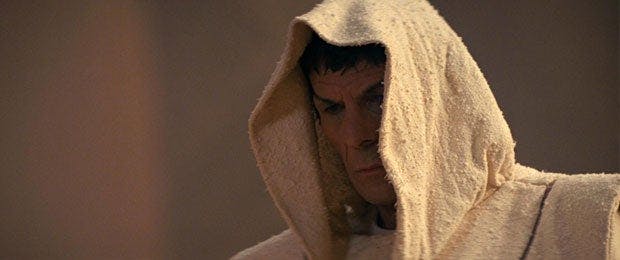

There’s more than meets the eye to such photo-editing. Essentially, you’re trying to determine just which, out of 10, 12 or 20 similar poses, is (one of) the very best photo(s). Genesis-grown Spock’s expression—as he modeled a stylish robe and eyed the crew parade at Trek III’s end—might be the same (non-commital) but the framing of each shot, his Vulcan manner, the expression on his friends’ faces all could differ in minor ways. There’s not necessarily one right photo but there are countless wrong ones. The trick is to, mostly, pick the good stuff.

In 1986, I was back again at the G+W Building, sifting through Paramount Publicity’s Trek IVbooks so as to create three different, all-color publications for The Voyage Home. Here’s what I recall about that experience: Peering and pondering and poring over hundreds of shots of the extremely wet Trek crew (and Catherine Hicks) and their borrowed Klingon Bird-of-Prey sinking into the stormy seas of Paramount’s... parking lot (site of the studio aquatic tank).

It got easier with subsequent Trek magazines. Now, instead of my going somewhere and studying contact books, Paramount wisely just sent us 250+ approved images. Studio photo editors did the hardest work of picking the best material; then, from that semi-finalist collection, I chose the 100+ slides we actually used. I even set up a second small desk in the office where my own loupe and a "light table" (a glass-sheathed box with fluorescent lighting within) awaited, so I could easily attend to photo-editing slides daily. I was a photo-editing fiend and personally selected 99% of the "art" used in the 475+ individual issues total of Starlog and all other magazine titles I edited.

With Next Generation and our other Trek TV publications, Paramount Licensing routinely FedExed us batches of 60-150 slides from each episode. Alas, those tallies included 15-20 variations of the same set-ups so, overall, fewer "different" images. Nonetheless, we managed.

Another small SNAFU was that, in television, still cameramen (then paid, I was told, $600+ daily) didn’t work every one of an episode’s five eight-day shooting schedule. With Next Generation, a budget-conscious publicity staffer would determine the script’s two most visually promising days (guest stars, alien planet soundstage sets, action sequences, location lensing) and a photographer would be hired just for them. On the first season’s "The Icarus Factor," Mitchell Ryan didn’t happen to work those days, so no shots of Riker’s Dad. As for "Home Soil," a photog wasn’t employed on any day... so no episodic pix at all! This problem would be solved later on by doing VHS or DVD "frame grabs" of un-still-photographed scenes. (Of course, very special episodes—like pilots and two-parters—got more photographer days.)

For the last 13+ years, there has been little necessity to look through contact sheets or fool around with color slides and glossy stills. As each new technology arose, arrays of specific images were made available digitally on jazz drives, zip disks, photo CDs. They were also emailed directly from publicists (as jpg, tiff, pdf, psd or other attachments). Or they could simply be downloaded from secure servers and authorized press-only websites, often without having to bother any human (i.e. a publicist). Editors could just log on and retrieve what was needed.

These days, everything’s digital (as on this website or any other). The initial source material may, in fact, be the same vintage slides, photos, book covers and other graphics I used years ago (which have now been scanned in to computers and digitized) or more modern images that actually originated digitally. Either way, there’s no need for anyone (save studio and network photo editors) to spend endless time looking at thousands of visuals, just to select the very best.

________________

David McDonnell, "the maitre’d of the science fiction universe," has dished up coverage of pop culture for more than three decades. Beginning his professional career in 1975 with the weekly "Media Report" news column in The Comic Buyers’ Guide, he joined Jim Steranko’s Mediascene Prevue in 1980. After 31 months as Starlog’s Managing Editor (beginning in October 1982), he became that pioneering SF magazine’s longtime Editor (1985-2009). He also served as Editor of its sister publications Comics Scene, Fangoria andFantasy Worlds. At the same time, he edited numerous licensed movie one-shots (Star Trek and James Bond films, Aliens, Willow, etc.) and three ongoing official magazine series devoted to Trek TV sagas (The Next Generation, Deep Space Nine, Voyager). He apparently still holds this galaxy’s record for editing more magazine pieces about Star Trek in total than any other individual, human or alien.

Copyright 2013 David McDonnell