Published Jul 16, 2013

Khan Was Almost... Harald Ericsson

Khan Was Almost... Harald Ericsson

StarTrek.com

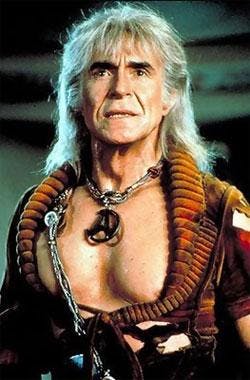

For the past five years, we have had the happy privilege of being able to study the archives of both writer/director Nicholas Meyer at the University of Iowa and those of Star Trek creator and visionary Gene Roddenberry at UCLA. Our research is inspired by what we consider an axiom of Mr. Meyer that “art thrives on limitations.” Limitations, be they of budget, time, censorship, technology, or perhaps self, can foster creativity in artists and filmmakers. There is likely no better example of this than Star Trek which was produced during the 1960s on both shoestring budgets and hampered timeframes.Our research has so far specifically focused on Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan and “Space Seed” for various reasons. First, TWOK is our favorite Trek film, and arguably the most important in the franchise. When it opened June 4, 1982, it had the possibility of reinvigorating the franchise if successful, or ending it, if a failure. Luckily, it was the former, opening with the biggest box office weekend gross in history to that point. Second, we have always admired Nicholas Meyer’s work, including his historic The Day After and his delightful Sherlock Holmes/Sigmund Freud pastiche The Seven Percent Solution. Third, Ricardo Montalban’s performances, both in “Space Seed” and TWOK, are nothing short of remarkable. Mostly, though, we wanted to learn and then share with fellow fans how this episode and film were made, and to celebrate all the artists, in front of and behind the camera, who created these amazing entertainments.For the next few Jefferies Tubes, we will shine a light on the secrets of “Space Seed” and what we learned from the various drafts, memos, budgets and production information of the Gene Roddenberry Archives and interviews we conducted with some of the artists who made the episode. We wish to thank CBS/Paramount, who granted us permission to study these archives, and it is our hope that the next time we all watch “Space Seed” the names on the credits will have more meaning. Star Trek thrived despite, or maybe because, of the limitations of the 1960s television world.PREPRODUCTION: The Script Part IThe story of Khan Noonien Singh begins before Star Trek ever premiered.Khan was actually born Harald Ericsson in an 18-page outline dated August 29, 1966 by journalist turned television writer Carey Wilber. Wilber is familiar to genre fans for his work on Lost in Space and had written for such TV classics as Bonanza.Titled “Space Seed,” this imaginative outline was submitted to producers Gene Roddenberry, Gene Coon, and Robert Justman for consideration as a possible episode a week before “The Man Trap” ever started the Star Trek legacy on Thursday, September 8, 1966. The outline began with an interesting question: “What would happen if a man of our age could be transported five hundred years into the future?” According to the outline, by the 1990s, humanity would be dealing with serious war and population problems and had resorted to the creation of space argosies that would transport criminals off planet to create more room for others. This is a world where “penalties are no weapon against despair.” This futuristic solution was rooted in the historical tradition of 18th century England, which sometimes gave prisoners choices of death or transportation to colonies.

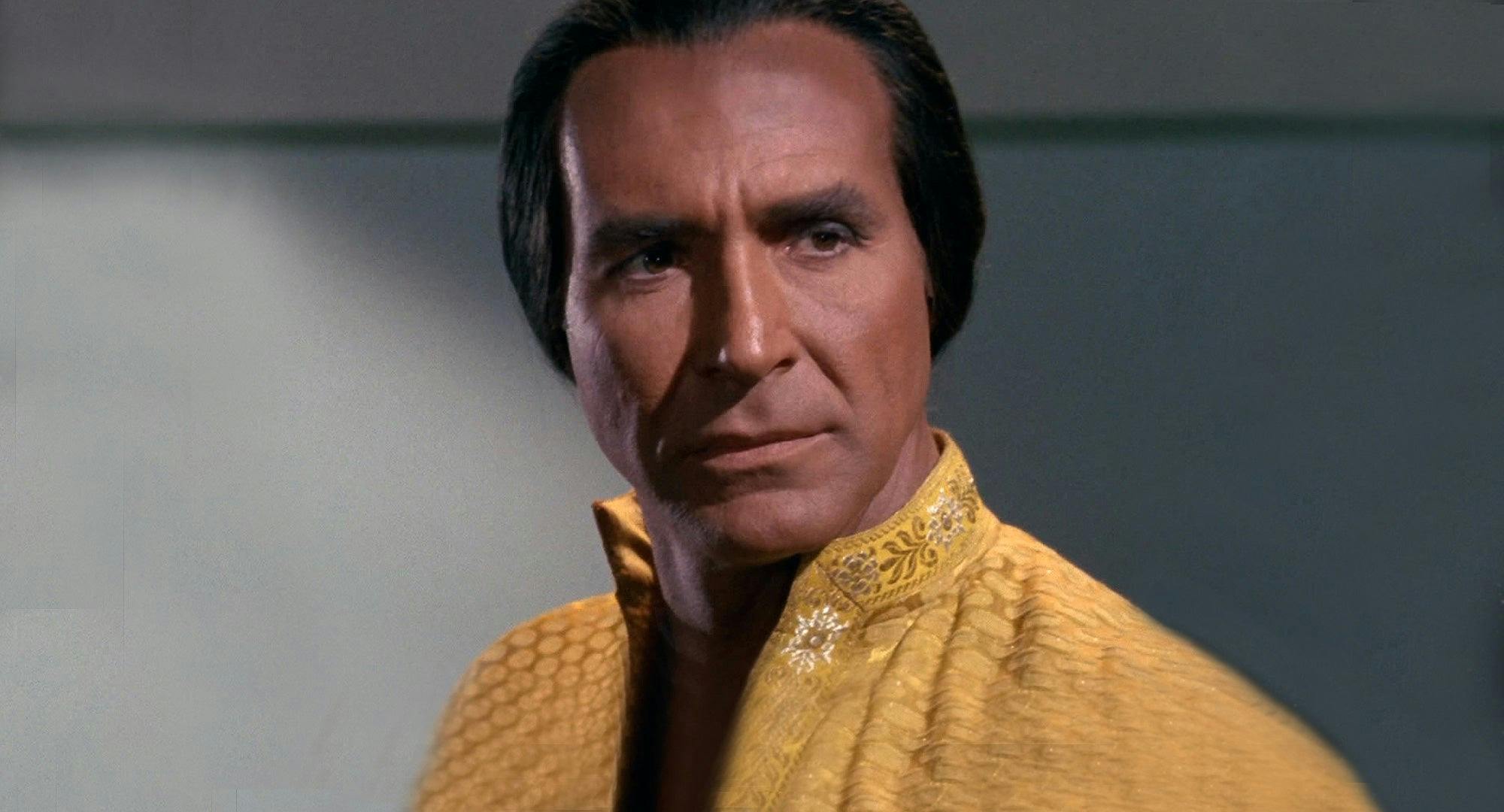

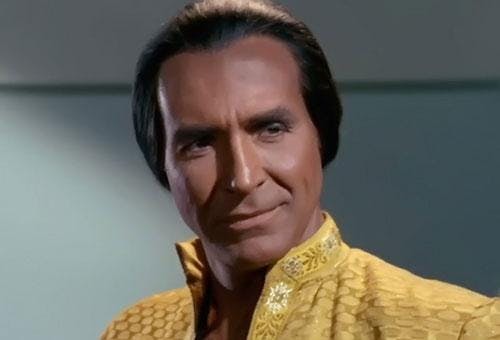

One such space ark was the Botany Bay. “She lifted earth in 2096 A.D. Her destination was CETI II. On board were one hundred transported criminals, male and female alike, a volunteer crew of six. Once the Botany Bay passed out of the solar system, this crew would join the passengers in a hibernation which would last fifteen hundred years.” Among the prisoners is a man named Harald Ericsson, a criminal with a “magnificent” body.However, something goes wrong 500 years into the future when the ship comes across the path of the U.S.S. Enterprise, and its automated weapon systems go online for the first time in five centuries. Interestingly, had the episode included this information it would have answered the question as to when in history the Star Trek series took place relative to the 1960s. Producer Gene Coon, responsible mainly for the writing staff and scripts, wrote a memo on September 2, 1966 to Wilber with suggestions and changes. One of his notes is that the creators of Trek did not want to reveal the actual time frame of the show. He writes, “As I mentioned to you, we have never determined the exact period in which this series is taking place. It could be a thousand years in the future, or as little as a hundred.” Of course, eventually, the time period would be specified as the 23rd Century.This was all backstory to the actual start of the episode as originally envisioned and would not have been shown, but rather revealed with dialog. The actual episode would have started with Sulu (who does appear in the actual episode) detecting a strange ship. Reading the outline is like reading an alternative version of “Space Seed” as some of the themes and characters are the same, and yet so much is different.

For example, the episode would have a different kind of Spock. It must be remembered that Wilber, and indeed, the world, had not yet seen Spock in action when he was writing the outline. He had only the writer’s bible with descriptions of the characters to guide him. The episode opened with Second Communications Officer Marla McGivers being teased about her fascination with the past by Janice Rand. Both McGivers’ role on the ship would be changed, and by the time “Space Seed” was filmed, Rand was no longer a character on the show.As Sulu has the conn, Captain Kirk is playing chess with Spock as McCoy watches. We learn that Spock defeated Captain Kirk by cheating (he tied the computer to his plays), which is discovered by McCoy. Spock is “mildly embarrassed.” Of course, the Spock we know would neither cheat, nor need to, and Gene Coon, who is much more familiar with how Spock was developing than Wilber would have been, in that same September 2nd memo tells Wilber that the chess scene must go.

Later, when the character of Ericsson is beginning to be suspected of being more than he lets on, Spock suggests the use some of his “peculiar methods” of the mind to get him to talk. Kirk reminds him that is illegal. While this seems again out of character, Spock will do almost exactly the same thing in Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country when needing information from Valeris.Most amazing is that Spock has what amounts to the Force! In the outline, when everyone else suspects that Kirk has died while being keelhauled (more on that next article!), Spock feels that Kirk is alive through an almost spiritual and psychic connection.During the next months, we will explore more of the making of “Space Seed,” including revealing the important changes to the character of Khan that occurred because of Joseph D’Agosta’s idea to cast Ricardo Montalban as the villain and the amazing role Gene Roddenberry had in saving the script at the last minute.SPECIAL THANKS: Nicholas Meyer, The University of Iowa, CBS/Paramount, UCLA, and StarTrekHistory.com

______________________________

Maria Jose and John Tenuto are both sociology professors at the College of Lake County in Grayslake, Illinois, specializing in popular culture and subculture studies. The Tenutos have conducted extensive research on the history of Star Trek, and have presented at venues such as Creation Conventions and the St. Louis Science Center. They have written for the official Star Trek Magazine and their extensive collection of Star Trek items has been featured in SFX Magazine. Their theory about the “20-Year Nostalgia Cycle” and research on Star Trek fans has been featured on WGN News, BBC Radio, and in the documentary The Force Among Us. They recently researched all known paperwork from the making of the classic episode "Space Seed" and are excited to be sharing some previously unreported information about Khan's first adventure with fellow fans. Contact the Tenutos at jtenuto@clcillinois.edu or mjtenuto@clcillinois.edu.