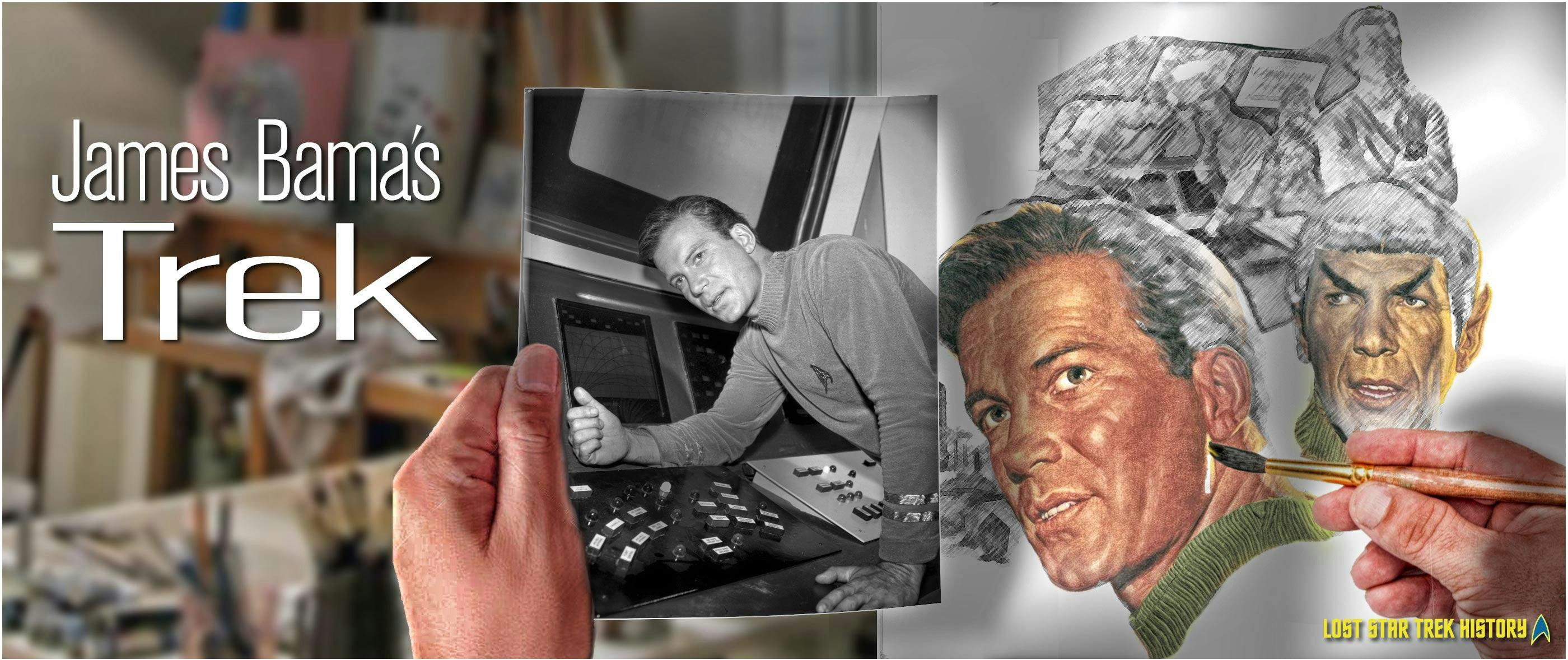

If you’re old enough to remember the 1966 premiere of Star Trek: The Original Series – and even if you’re not -- you’re undoubtedly familiar with one of the very first teaser images released for it. The image we’re talking about – a montage showing Captain Kirk, Mr. Spock, assorted crew, and the Enterprise blasting its rockets around a strange planet -- appeared in promotional material that NBC used to advertise the show. Initially, the montage looks like a collection of photographs but, amazingly, it’s actually a lifelike painting. The artwork, by professional illustrator and photographer James Bama, has become iconic in Star Trek, and in this article, we take a closer look at it as well as the man who painted it.

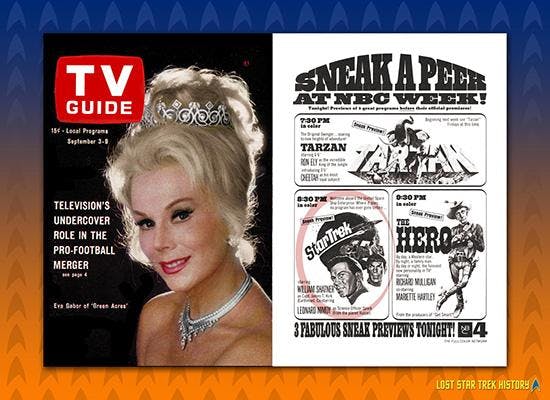

Above: The publicity spread for NBC’s “Sneak A Peek at NBC Week” in TV Guide (the September 3-9, 1966 issue) used the Star Trek art Bama created.

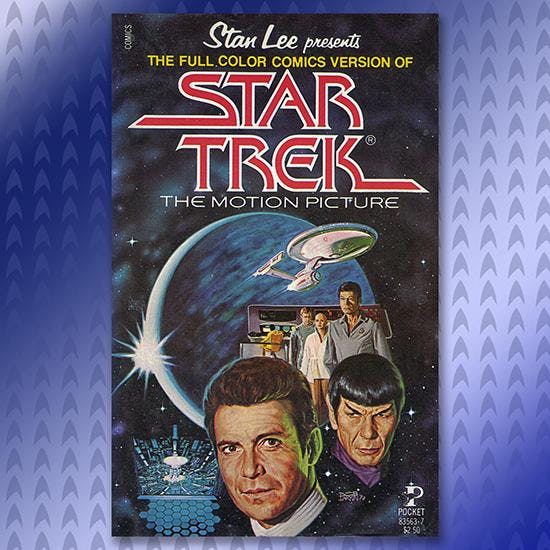

Above: Bama’s Star Trek art was honored by Bob Larkin in his cover for the comic adaptation of Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

James Bama

James Elliott Bama is an American artist and photographer who was born in New York in 1926. While growing up there, he became a comic-strip fan and developed his drawing and painting abilities by copying them. Bama’s talent emerged at an early age and, in fact, he made his first professional sale (to the New York Journal-American) at just 15.

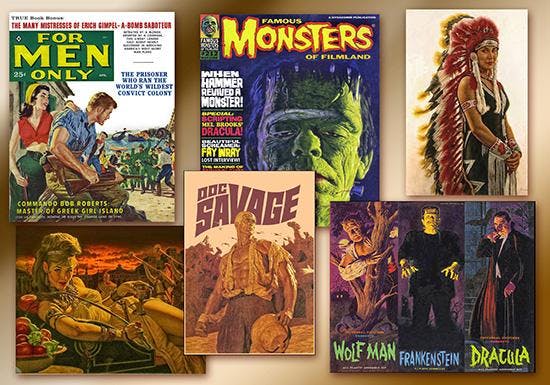

In 1950, Bama became a commercial illustrator and entered the public’s view with a book illustration done for Nelson Nye’s A Bullet for Billy the Kid. He then spent approximately 20 years illustrating covers for Doc Savage and other books, covers and interiors for men’s pulp and horror magazines, boxes for monster model kits, and many other works. Overall, it’s estimated he did 100’s of commercial illustrations/paintings.

In 1966, Bama’s interests took a sharp turn when he and his wife visited Cody, Wyoming, and fell in love with it. While there, Bama found himself attracted to painting the western people and landscapes he saw. Not surprisingly, and not long afterward (in 1968), he and his wife permanently relocated there from New York. In 1971, Bama stopped doing commercial illustrations, by-and-large, and concentrated on contemporary western art.

Above: An assortment of Bama’s art, including one of his western paintings and a few that were used on (and in) books, magazines and model boxes.

Realism

As can be seen in his work, Bama pursued realism as an artistic style, which, as that term implies, involves depicting objects as accurately as possible. Historically, the realism movement in the visual arts started in France after the 1848 Revolution, and it was picked up in the United States and elsewhere shortly thereafter. As an artistic style, it blossomed globally at the beginning of the 20th century.

In order for an artist to be an effective realist, they must possess a keen eye and the ability to accurately reproduce the details of the object they’re looking at. The ideal situation for the artist, of course, is to reproduce the object in real time, but that’s not strictly required. In Bama’s case, where many of his subjects didn’t exist, he often used models, or photographs, to represent what he would paint. For example, his version of Doc Savage was based on male model Steve Holland. And, as a notable TOS coincidence, one of his frequently used female models was Andrea Dromm, Yeoman Smith from “Where No Man Has Gone Before.”

The Star Trek Art

Not long after TOS was picked up as a series, NBC commissioned Bama to paint a piece of promo art. One of NBC’s initial concepts was for the art to be reproduced as a poster that they could sell to the general public for $1. Their ad campaign was to be similar to the one used for their other shows, such as I Spy, Bonanza (for which Bama also did the promotional illustration), The Man From U.N.C.L.E and Get Smart. However, for whatever reason, NBC did not do this with the TOS poster, but instead provided it to select advertisers and individuals. Also, in addition to Bama’s art being used on the poster, it also found duty in NBC’s other promo and ad materials, including print ads and television commercials.

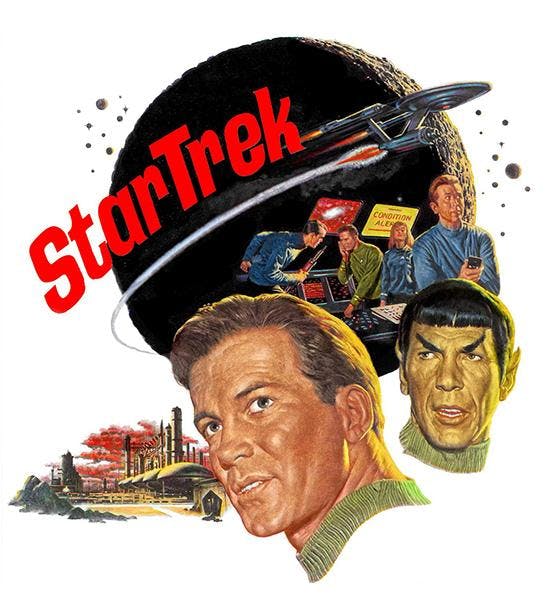

Above: One printed version of Bama’s artwork. Sharp-eyed observers will notice that several variations of it can be seen, with one of the major differences involving the words “Star Trek” in front of the planet. These words were originally on a transparency that could be removed or changed depending upon how the art was to be used. For example, when the art was going to be shown in black and white, text with a white font where it overlapped the planet was used so that the words could be read. Another variation of the art, not shown here, features Bama’s signature in the lower left, beneath the lithium cracking station on Delta Vega.

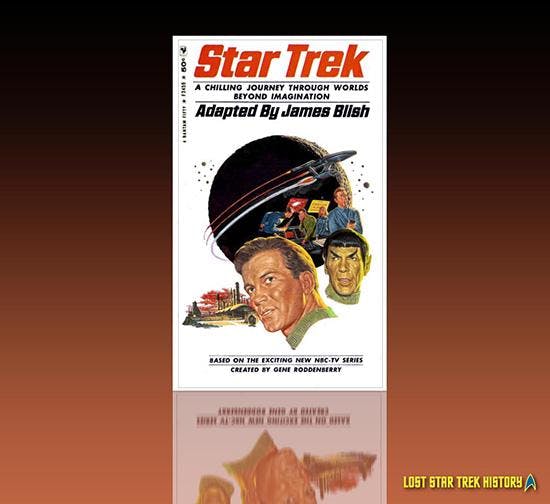

Above: One notable use of the Bama TOS art was on the cover of James Blish’s first book adaptation of the TOS episodes.

As mentioned previously, Bama often used models to represent what he wanted to include in his art in order for the latter to be as realistic as possible. For his Trek work, he was provided with early publicity and episode stills from “Where No Man Has Gone Before.”

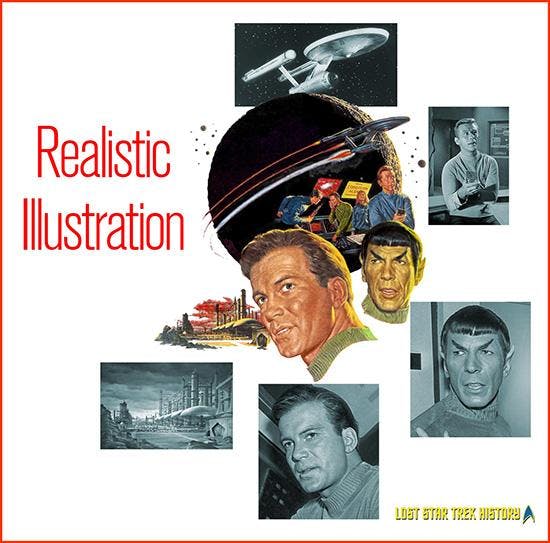

Above: Bama’s art surrounded by an assortment of stills that he likely used for assistance while painting. For the most part, the images in the photographs were translated into the painting accurately; however, two notable exceptions are the background characters (crew) and the Enterprise. With regards to the former, we conjecture that there was no need to accurately reproduce the crew in the art since they were in the background. And with regards to the latter… well, his painting is actually close except for the egregious flames shooting from the nacelles and shuttle bay. In our research, we found that Bama was a Flash Gordon comic strip fan, so, since he was unfamiliar with the operation of this new U.S.S. Enterprise, we wonder if he didn’t take some artistic license from that strip’s ships. (As a sidebar, note that the Enterprise in his painting seemingly shows a pointed spire on the nacelle hemisphere. A close examination of the painting, however, reveals the spire is a smoke or vapor trail, perhaps from the planet.)

Additional Information about the Artist

Bama, who is still alive but no longer painting, was an incredible artist, and he provided Trek with an unforgettable illustration that’s still cherished today. For further information about Bama and his work, we recommend The Western Art of James Bama by James Bama (Bantam Books, 1975), The Art of James Bama by Elmer Kelton (Bantam Books, 1993), and James Bama: American Realist by James Bama and Brian M. Kane with Harlan Ellison and Len Leone (Flesk Publications, 2006). For a good online source of additional information, including an interview with the artist, this webpage (and associated links) are also recommended.

Biographical Information

David Tilotta is a professor at North Carolina State University and can be contacted at david.tilotta@frontier.com. Curt McAloney, an accomplished graphic artist, resides in Minnesota and can be reached at curt@curtsmedia.com. Together, Curt and David work on startrekhistory.com. Their upcoming book, Star Trek: Lost Scenes (due out in August 2018 from Titan Books), will be filled with hundreds of carefully curated, never-before-seen color photos that they use to chronicle the making of TOS, reassemble deleted scenes left on the cutting-room floor, and showcase bloopers from the first pilot through the last episode.