Published Mar 4, 2012

"Doomsday" & More With Norman Spinrad, Part 2

"Doomsday" & More With Norman Spinrad, Part 2

You’ve been in the news lately because “He Walked Among Us” resurfaced. Let’s go through the history. After you did “The Doomsday Machine,” you wrote “He Walked Among Us” as a second Star Trek script. How did that script initially come to be and how/why did it vanish?

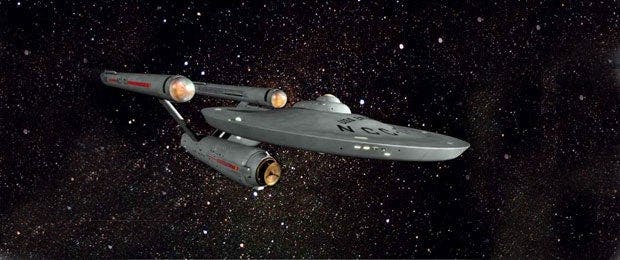

Spinrad: I was invited to do something specific. Milton Berle wanted to do a Star Trek, or they wanted Berle. People argue about this, but the way it was said to me was that Berle wanted to do it as a serious dramatic actor, which he had been. He had a second career as a good character actor. He was good. They said that out on the back lot, in a weedy old field, they had this primitive village (set), so they said, “See if you can do something for Berle and work that set into it.” They figured I could write to budget, and I could. So I went out and looked at the weedy field. I was interested in the paradoxes of the Prime Directive, and that’s what the thing was really about. Berle was supposed to play Bayne, a sociologist, a guy trying to do good, who ends up on a more primitive planet. It’s sort of like A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. If you’re going to steal, it’s better to steal from Mark Twain or Herman Melville than Fred Saberhagen. So he’s there playing God and he’s violating the Prime Directive. He’s screwing things up, so the Star Trek crew has to find a way to get him out of there without violating the Prime Directive themselves. That’s the basic argument. It’s a complicated moral question that it’s really built around, and Gene (Roddenberry) had written that sort of thing himself.

And then?

Spinrad: I was happy with what I had done. It was accepted. They paid for the full thing, the first draft, second draft polish. I got all my money. Then, Gene Coon, who was the story editor-cum-producer at the time, decided – and he’d done this with several other scripts – “This thing needs some rewriting. Who can I really trust to do it? I know… Me!” And he copped a lot of credits and, therefore, residuals. I don’t think he or I or anyone else realized what those residuals were going to be worth. And he rewrote it into an unfunny comedy. First, I complained to Gene Coon, because I was really angry and it was really crap. I complained about it and he said to me, “Shut up and play ball with me kid, and you’ll be making $100,000 a year. If you don’t, you won’t be writing for this show again.” That was the wrong thing to say to me. That just clinched it for me. I called up Gene Roddenberry and I said, “Gene, don’t embarrass your show by shooting this piece of $&*@. Kill it. Don’t shoot it. Kill it.” That was kind of a surprising thing for Gene Roddenberry to hear, but I said, “Read it, Gene. Just read it.” Gene read it and killed it.

Fair enough, but most freelance writers, they hand in a script, get their money and see the episode when it airs. How did you manage to read Coon’s re-write?

Spinrad: How was it I ended up seeing Coon’s version of the script? I don’t really remember, but, you see, I had a good relationship with Roddenberry. I was on the set of “The Doomsday Machine.” But I don’t remember how I ended up seeing the script. Maybe they ended up just giving it to me. I had a good relationship with Bobby Justman, Dorothy Fontana, Gene Roddenberry. Maybe things (then) were not quite like they are now. Also, come to think of it, in those days at least, the Writers’ Guild determined credits and you had a right to contest it if you didn’t like it. So maybe in those days they had to show (the final draft to) everybody who’d worked on a script. Maybe it’s something like that.

OK, now back to the timeline. Roddenberry agrees to kill your script. How did it go missing?

Spinrad: Remember, this is 1967, I was writing on a manual typewriter with carbon paper. So I had a carbon copy of this thing. Then, later, I donated a bunch of my papers to Cal State Fullerton. That was in it and they said, “Oh, don’t worry. If you ever need it, you can just come and get it.” Well, that turned out not to be true. That program collapsed. I don’t know what happened to the rest of my stuff. This was not a thing where you could make a million disks. Everything was either a photocopy or carbon copy. So it just disappeared, and I don’t think Gene Coon wanted many copies of it around.

Some fans have pointed out that the missing script wasn’t all that missing, as it had made the rounds across the Internet and the dealers’ rooms on the convention circuit…

Spinrad: I just had some fans say something on my blog, that it was for sale on eBay and someplace else. I checked it out and what they were selling was the script with Coon’s name on it, too, not this.

By the way, you mentioned an unpublished novelette of yours that inspired “The Doomsday Machine.” Is that going to show up, too, 45, 50 years later?

Spinrad: No. God knows where that is. This is well known; it got rejected by all these magazines.

Let’s bring everyone up to speed. What are you working on these days?

Spinrad: I just finished the first draft of my latest novel last week. It’s called Police State. It’s a near-future novel set in New Orleans in which the police, step by step, become revolutionaries in a strange kind of way. It’s also about the nature of New Orleans, and what’s going to happen in the future to New Orleans. I spent two weeks down there doing a lot of research and having a lot of fun. It about many things: voodoo and the politics of Louisiana, the mortgage crisis, and what the rising levels do to the city and, by extension, every place else. I’m not going to self-publish, but I don’t have an American publisher yet. I haven’t finished the book. I plan to spend another month in New Orleans to rewrite the book there and get the flavor and get everything really right. That’s been my focus, completely, for the past 11 weeks. What else am I doing? My usual Asimov column. But I usually only write one thing at a time if I can help it.

Click HERE to visit Norman Spinrad's official blog/site and click HERE to read part one of our StarTrek.com interview with Spinrad.